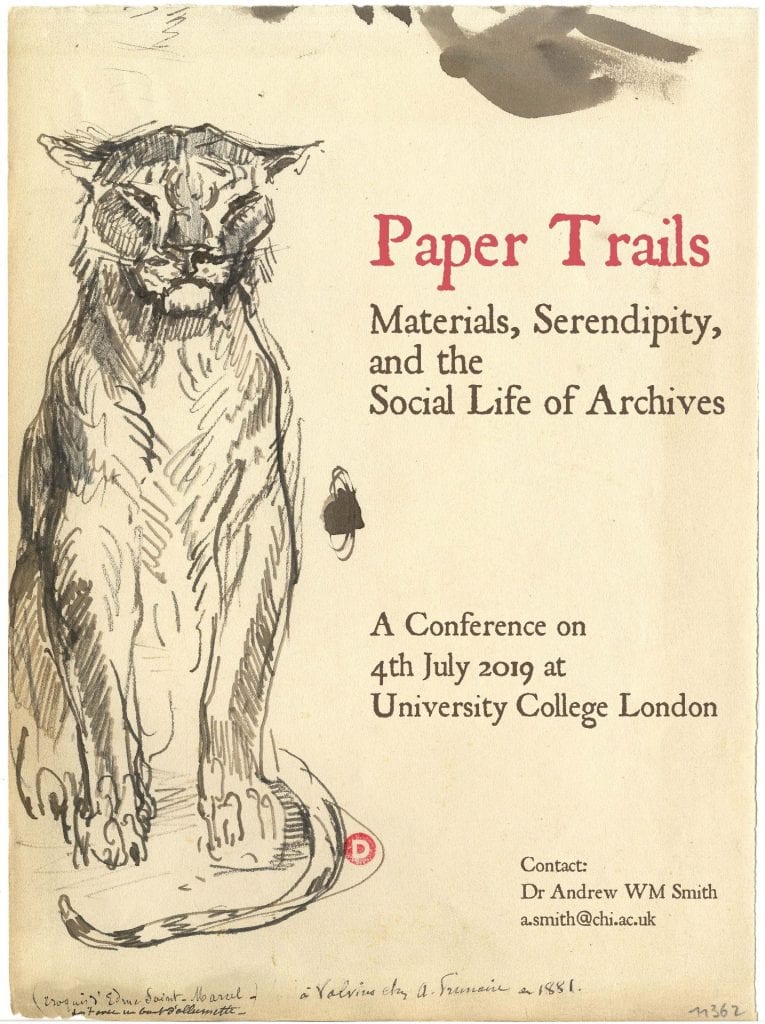

The Power of Print

By Vicky A Price, on 19 February 2020

The Outreach team at UCL Special Collections have spent a great six weeks delivering an after school club to Year 7, 8 and 9 pupils at William Ellis School. Pupils attended in their free time to explore how written texts have been produced through the ages and to learn about some of the ways printing has influenced western society.

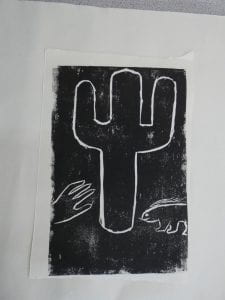

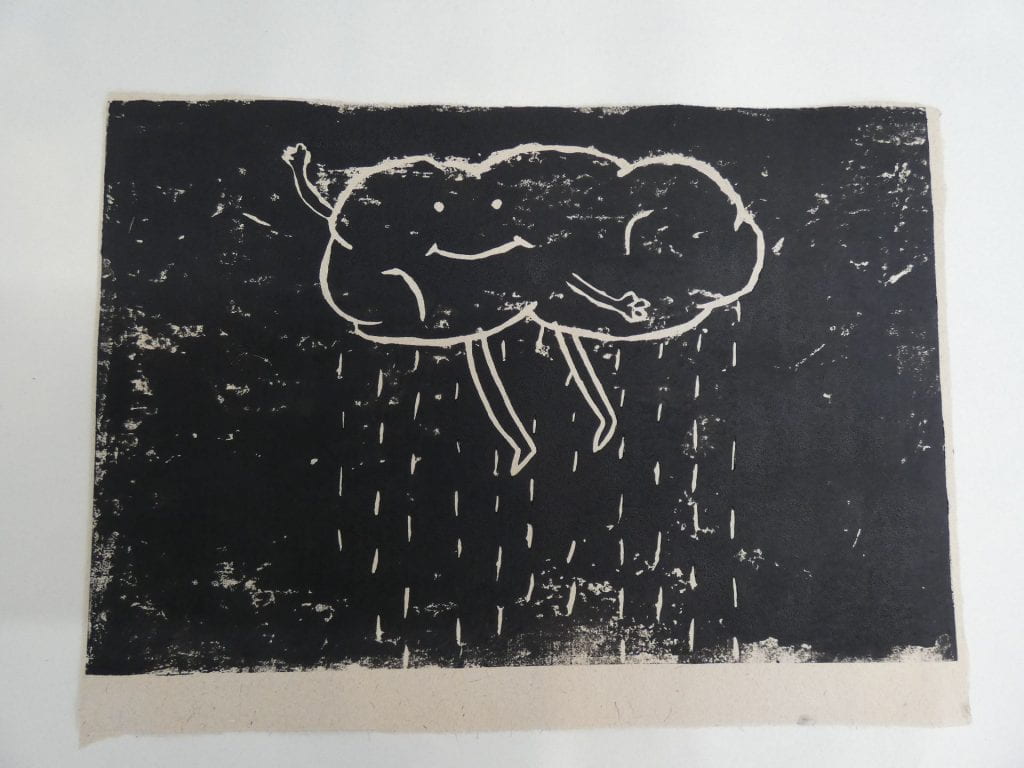

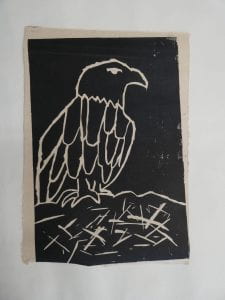

Each session involved a hands on art or craft activity, producing manuscripts complete with calligraphy and gold leaf, block prints of historiated initials and lino cut illustrations. We are proud to share the end results of this final task with you – pupils were asked to choose a poem from a selection and to create an image they felt represented the poem in a lino print.

Porcupines

By Marilyn Singer

Hugging you takes some practice.

So I’ll start out with a cactus.

(Poem taken from the Poetry Foundation)

Trees

By Joyce Kilmer

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

(Poem taken from the Poetry Foundation)

Extract from The Cloud

By Percy Bysshe Shelley

I bring fresh showers for the thirsting flowers,

From the seas and the streams;

I bear light shade for the leaves when laid

In their noonday dreams.

From my wings are shaken the dews that waken

The sweet buds every one,

When rocked to rest on their mother’s breast,

As she dances about the sun.

I wield the flail of the lashing hail,

And whiten the green plains under,

And then again I dissolve it in rain,

And laugh as I pass in thunder.

(Poem taken from The Poetry Foundation)

To Catch a Fish

By Eloise Greenfield

It takes more than a wish

to catch a fish

you take the hook

you add the bait

you concentrate

and then you wait

you wait you wait

but not a bite

the fish don’t have

an appetite

so tell them what

good bait you’ve got

and how your bait

can hit the spot

this works a whole

lot better than

a wish

if you really

want to catch

a fish

(Poem taken from The Poetry Foundation)

The Eagle

By Alfred, Lord Tennyson

He clasps the crag with crooked hands;

Close to the sun in lonely lands,

Ring’d with the azure world, he stands.

The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls;

He watches from his mountain walls,

And like a thunderbolt he falls.

(Poem taken from The Poetry Foundation)

Close

Close