Dangers and Delusions: Promoting women’s voices through an exhibition

By Helen Biggs, on 28 June 2018

Written by Jessica Womack and Helen Biggs. A version of this blog post was first presented at the Education, College Women and Suffrage: International Perspectives conference at Royal Holloway on Wednesday, June 13 2018, as part of the panel, Journey in Gender Equality: University College London, Women and Suffrage, 1878-2018.

2018 marks 100 years since the franchise was first extended to (some) women in Britain. The anniversary is being celebrated across the UK (as well as here at UCL), and it seemed like the perfect opportunity for UCL Special Collections to showcase some of the women’s suffrage (and anti-suffrage!) items in our collections. It was hoped that this would help to redress one of the noticeable weaknesses in our past exhibitions: a lack of women’s voices.

While many of our collections are hugely historically significant, women are under-represented within them. It’s not just a question of whether historically women were writing, or researching, or creating, and whether those works have been published or recognised. It’s also a question of whether the collectors whose libraries and archives we now hold considered women’s works to be worthy of collection. With the exception of the occasional standout – a Mary Sidney or Wollstonecraft – very often they did not.

It’s also worth noting that most of the collections we have purchased or received over time were collected by men – so we hold material collected by men, written by men, and generally, on subjects which were considered to be of interest to men. Creating ‘Dangers and Delusions’?: Perspectives on the woman’s suffrage movement was an opportunity to elevate the women’s voices that we do have in our collections, but one not without its difficulties.

While Special Collections holds a great many beautiful books, striking magazines, and fantastic photographs, most of our materials are paper, which is difficult to display. It is often unattractive and doesn’t draw the eye – it’s flat, both literally and figuratively. This is a challenge when creating any exhibition from our collections, as what we display has to be relevant to the exhibition’s theme – but not so boring to look at that no one will notice it.

Extract from Alexandra Wright’s letter to Karl Pearson, 1907 [PEARSON 11/1/22/112]

When possible, we want our exhibitions to create connections between our collections, our exhibitions theme, and UCL itself. Sometimes these connections are easy to make. For examples, included in Dangers and Delusions is a letter from Alexandra Wright (who worked or studied in UCL’s Biometric Laboratory) to Karl Pearson (who ran it.) The letter contains Wright’s account of a women’s suffrage meeting that was broken up somewhat violently by male medical students from UCL and other London universities. In this, the connections to both UCL and women’s suffrage are very clear.

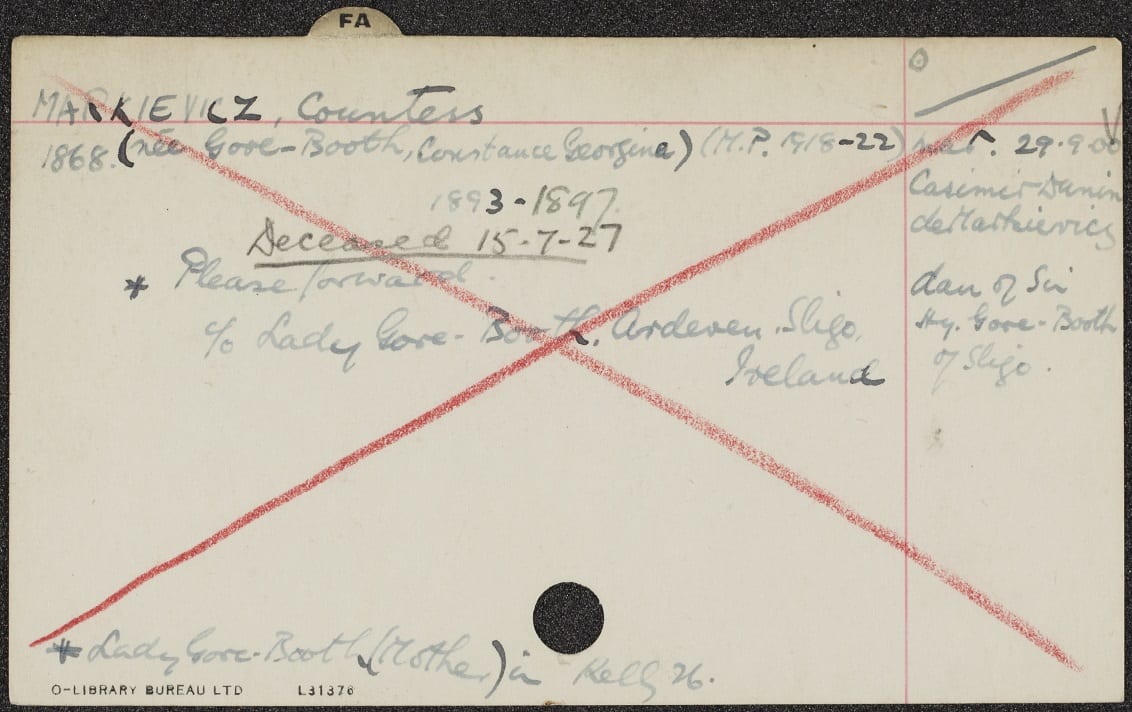

On the other hand, the student record card for the Countess Markievicz, née Constance Gore-Booth, requires quite a bit of explanation. Unlike Wright’s letter, which explicitly mentions both suffrage and UCL, the record card doesn’t state that Markievicz attended the Slade, or that she was one of the first women elected to Parliament. This means that without prior knowledge, exhibition visitors can’t make the connections themselves, but need to be given extra information to do so. Creating the “interpretation” – context – for items such as this can be both challenging and time consuming.

Student record card for Constance Markievicz [UCLCA/SA]

Unfortunately, our copies of the works in which he expresses his more positive views of women’s legal rights were not available to display in the exhibition. Instead, we included An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation, in which Bentham writes that woman is ‘commonly inferior’ to man in strength, knowledge, intellect and ‘firmness of mind.’ These sentiments are very similar to those expressed by anti-suffrage campaigners featured in the exhibition; to present them together erroneously suggests that Bentham was also against women’s suffrage, when his views on women, and women’s legal and political rights, were more complex than wholly accepting or rejecting the idea that men and women were equal.

In retrospect, as we were unable to fairly represent Bentham’s views, a better decision may have been to not include any of his writings, even if this meant that the exhibition drew a smaller audience overall. Besides the misrepresentation of Bentham, including his work did privilege anything he had to say about women over what women have to say about themselves.

The importance of creating a clear narrative for the exhibition meant that some of our collections which do have a strong focus on women could not be included. Early on in discussions around the exhibition, the idea of looking at how the fight for equality developed into second wave feminism, and radical Women’s Lib movements, was floated. This would have allowed us to represent women who often don’t make it into the university archives (as those who did in the early 20th Century were often white women of a middle-upper class social status, many of whom were related in some way to male academics at UCL.) But ultimately the exhibition focused more narrowly on reactions to women’s suffrage, and other women’s movements weren’t relevant to the theme.

So how successful were we in elevating women’s voices in our exhibition? Over half of the items in Dangers and Delusions are created or co-created by women or women’s groups; not as high as one may hope and yet a marked improvement on last year’s exhibition, where only two displayed items could definitely be attributed to women.

Ideally, future exhibitions would aim for similar numbers, or work towards promoting other under-represented and marginalised groups. However, we will always be restrained by the collections we hold – we can’t show material that we don’t have. What we can do is continue to look for the people in our collections who have always been ‘hidden’ – the unnamed, the ignored, the notes scribbled in the margins – and work towards making them more visible.

‘Dangers and Delusions’?: Perspectives on the women’s suffrage movement is open in UCL’s Main Library until December 14. More events exploring women’s suffrage and the women of UCL can be found at UCL Vote 100. Finally, in the newest edition of The World of UCL, published this month and freely available online, Dr Georgina Brewis has added much new material on the role of women at UCL – a long overdue revision.

Close

Close