Becoming an Historian at Kelmscott Secondary School

By Vicky A Price, on 17 December 2021

The Outreach programme at UCL Special Collections delivers free projects for schools and community groups in Camden, Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Newham and Waltham Forest.

We have recently completed an after-school programme with a group of talented young historians at Kelmscott Secondary School in Waltham Forest. While learning how to ‘become an historian’ they decided the following skills were essential:

A Great Historian…

1) Uses multiple sources

2) Is aware of bias at all times

3) Is thorough and looks outside the box

4) Enjoys the process

5) Reads between the lines

6) Takes great care of primary sources.

These are certainly wise words, and they set themselves a high bar, doing everything they could in a short period of time to follow these principles. Here are the fruits of their labour, in their own words – participants chose collection items to research and interpret on this blog:

The Trevelyon Miscellany (MS Ogden/24)

By Mary, Jasmine, Delphi, Rosa

While studying the Trevelyon Miscellany at our school’s history club, organised by the Head of Outreach at UCL Special Collections, we have learnt a lot regarding the 17th century manuscript. It’s believed to be created and published by Thomas Trevelyon around 1603. It consists of a variety of information, such as the dates of various monarchs’ births, deaths and accessions since William the Conqueror, as well as historical events, recent inventions of the time, biblical stories, charts of roads and portraits of rulers. It also includes nice patterns at the back.

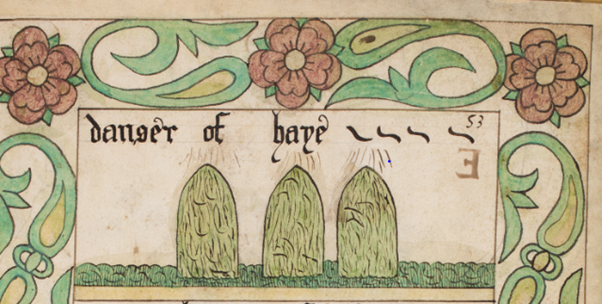

We were drawn to it by the interesting illustrations and illuminations, one of which is shown below.

A close up of part of a page in the Trevelyon manuscript.

Before coming into the UCL’s collection the Miscellany was owned by Charles Kay Ogden. We were intrigued by letters written to Warden Lock in Oxford in the 20th century about the item. They were written by a H. A. Wilson, R. L. Poole and ‘Allen’. They show an interesting and unique perspective into the thoughts and historical beliefs of the time. For example, a letter from H. A. Wilson to Lock details all the correct and incorrect dates of monarchs’ deaths, births and ascensions in the Miscellany. Speaking of unique thoughts, after much research we still have no idea what the ‘dangers of hay’ are.

Interviews with young apprentices in a House of Correction, Cold Bath Fields from 1837 (Chadwick 3/2/1)

By James

My item was commissioned by Edwin Chadwick, who wanted to know what it was like in a house of correction at the time and to work out why so many children were there. Inmates consisted of both genders at all ages.

A page from the Chadwick archive item.

While researching the item, I discovered a mortality record of Cold Bath Fields which was a ‘house of correction.’ I decided to study this item because I wanted to see what it was like in a workhouse because I visited one that was made into a museum when I was in primary school on a school trip.

I found out that during the years, 1795 – 1829 there were 376 deaths. Something very interesting I found out is that there were 15 child deaths during that thiry-four year period.

Here are two quotes I found from a writing about this place by Thomas R. Forbes. This is about what they had to go through on a day to day basis. They “picked old hemp ropes into oakum or separated stiff fibres of coir from outer shells of coconuts”.

This one is about the conditions that were in the workhouse: “The dungeons were composed of brick & stones, without fire or any furniture but straw, and no other barrier against the weather but iron gates”.

Something quite interesting is that 85 out of the 376 deaths (22.6%) were female. This may mean that most people there were male or that women were treated differently (better) from men back then.

This is where I got a lot of my information.

Fragment of a copy of Euripides’ Medea (MS Frag/Gre/1)

By Cameron

UCL Special Collections’ oldest item – a Greek manuscript fragment from the 4th or 5th century.

I decided to study Euripides as he is someone I had heard of before and wanted to learn more about.

Medea is a play written in 431BC by Euripides, a Greek playwright who was the son of Mnesarchus and his wife Cleito. His writing continued to influence literature well into the 12th century.

Early life

He came from a well-off family and was a pupil of Aristotle.

Adulthood

Once Euripides had grown up he went into playwriting and poetry. Sadly he didn’t gain too much popularity as he was always outshone by Sophocles.

He also ran into some trouble with Kleon who prosecuted him for blasphemy after he disrespected the “immortals” however no evidence has been found of the outcome of this trial

Euripdes sadly passed away around 485 BC

Medea is only one of his famous plays – he wrote quite a few over his lifetime, and if you would like to I’m sure there’s info you can find on certain websites. I even encourage you to as I find his work very interesting.

Sources: Encyclopedia.com, which contains information from David Kovac’s Euripides.

Euripides and Feminism

By Isabella

I have chosen to focus on Euripides’ thoughts on women because by appreciating the modern concepts in Euripides plays we can understand the impact they would have had in Ancient Greece. The fragment we have is from Medea which is an important play for women because Medea is a girlboss; she is a multi-layered character who has her own opinions and ambitions.

“We are women, quite helpless in doing good but surpassing any master craftsman in creating evil”

While Medea could be considered a bad person and maybe didn’t represent women in the best light she still subverted the stereotypes women were expected to obey in Ancient Greece. They definitely weren’t supposed to murder their children.

Sources:

Pandora’s Jar by Natalie Haynes

Close

Close