“Chief City of Airstrip One”: George Orwell and London

By Sarah M Gibbs, on 14 January 2019

George Sidney Shepherd (1784-1861). London University from Old Gower Muse (1835) (UCL Art Museum 4587)

Migrating Words, a creative writing workshop inspired by literary and artistic representations of London, will take place at UCL Art Museum on Wednesday, 16 January 2019 from 6 to 8 pm.

In the opening pages of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), the novel’s protagonist, Winston Smith, gazes at a scene of urban decay:

He tried to squeeze out some childhood memory that should tell him whether London had always been quite like this. Were there always these vistas of rotting nineteenth-century houses, their sides shored up with baulks of timber, their windows patched with cardboard, and their roofs with corrugated iron […]? And the bombed sites where the plaster dust swirled in the air […]? (5)

Though Orwell was born in Bengal, and preferred life on an isolated Scottish island to the bustle of the city, he is inextricably linked to London. An investigative journalist as well as a novelist, he is famous for having gone “native in his own country.” That anthropological expedition involved transgressing geographic, as well as class, boundaries. “I wanted to submerge myself,” he writes in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), “to get right down among the oppressed, to be one of them and on their side against their tyrants” (148).

Orwell’s novels and non-fiction return continually to London and provide a cross-section of its places and people through prosperity, depression, and war. UCL Culture’s upcoming creative writing workshop, Migrating Words, takes its inspiration from Orwell’s texts, and the representations of the city in UCL Art Museum’s collection. The words and images align and diverge, contradict and complement one another in their portrayal of a centre that began as a far-flung outpost of a dying empire, and became a global centre. The world has come to London.

* * *

Orwell’s novels of the 1930s engage directly with urban poverty. Dorothy Hare, Orwell’s heroine in the 1935 novel A Clergyman’s Daughter, is recently returned from hop picking in Kent and desperately seeking shelter:

It was not until the evening that Dorothy managed to find herself a room. For something like ten hours she was wandering up and down, from Bermondsey into Southwark, from Southwark into Lambeth, through labyrinthine streets where snotty-nosed children played at hop-scotch on pavements horrible with banana skins and decaying cabbage leaves. At every house she tried it was the same story—the landlady refused point-blank to take her in. (95)

The narrator’s description of conditions near the Thames contrasts sharply with seventeenth-century artist Wenceslaus Hollar’s rendering of the glory of Lambeth Palace.

In Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936), failed writer Gordon Comstock, who lives a life of principled penury, wanders drunkenly through central London. While James Dickson Innes’s 1908 oil painting portrays the elegance of aristocrats’ night at the theatre, Gordon’s hatred of the “money god” and the strictures of work and wealth casts a deathly pall on the West End:

“We’d better walk up to Piccadilly Circus,” he said. “There’ll be plenty of taxis there.”

The theatres were emptying. Crowds of people and streams of cars flowed to and fro in the frightful corpse-light. (192)

James Dickson Innes (1887-1914). A Scene in a Theatre: A Performance Seen from a Box in which Three Figures are Standing (1908) (. UCL Art Museum 5263).

Both Orwell and Fairlie Harmar had an intimate knowledge of London accommodations for the poor. The latter created the undated watercolour Old and Helpless—Saint Pancras Workhouse, while Orwell describes the conditions in the institutions’ casual wards, termed “spikes,” in a 1931 essay; he also refers to workhouses in his first book-length publication, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933):

At half-past eight Paddy took me to the Embankment, where a clergyman was known to distribute meal tickets once a week. Under Charing Cross Bridge fifty men were waiting, mirrored in the shivering puddles. Some of them were truly appalling specimens–they were Embankment sleepers, and the Embankment dredges up worse types than the spike. (198)

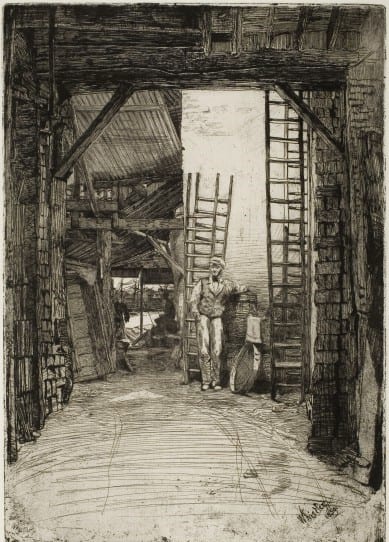

Also in Down and Out, Orwell describes a day’s idling in the Thames district. James Whistler portrays a similarly ramshackle, chaotic river life in Black Lion Wharf, an etching he completed in 1859.

All day I loafed in the streets, east as far as Wapping, west as far as Whitechapel. It was queer after Paris; everything was so much cleaner and quieter and drearier. […] In Whitechapel somebody called The Singing Evangel undertook to save you from hell for the charge of sixpence. In the East India Dock Road the Salvation Army were holding a service. […] On Tower Hill two Mormons were trying to address a meeting.” (143-144)

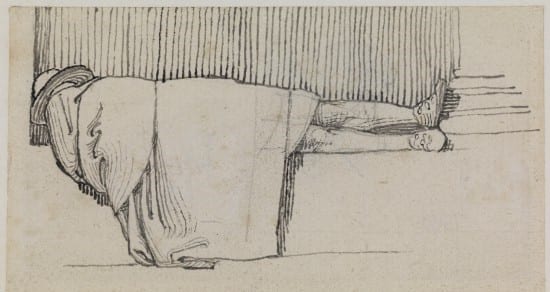

John Flaxman was one of the foremost funerary sculptors of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and casts of his Greco-Roman style monuments are a cornerstone of UCL Art Museum’s collections. His pen and ink drawings, however, often diverge from neoclassical subjects. A Man in a Cloak Asleep on the Plinth of a Building (undated) co-locates indigency and architectural grandeur. Orwell does the same in A Clergyman’s Daughter, drawing the wandering Dorothy to London’s triumphal center:

Dorothy turned to the left, up the Waterloo Road, towards the river. On the iron footbridge she halted for a moment. The night wind was blowing. Deep banks of mist, like dunes, were rising from the river, and, as the wind caught them, swirling north-eastward across the town. A swirl of mist enveloped Dorothy, penetrating her thin clothes and making her shudder with a sudden foretaste of the night’s cold. She walked on and arrived, by the process of gravitation that draws all roofless people to the same spot, at Trafalgar Square.” (100)

John Flaxman (1755-1826). A Man in a Cloak Asleep on the Plinth of a Building (undated)(UCL Art Museum 776).

It is Rome, rather than London, that is called the Eternal City. Orwell, however, never visited Italy. Instead, he lived, loved, suffered, was celebrated, and most importantly, wrote in London; it is his city of the past, and the future. For the capital endures even in the nightmare world of Nineteen Eighty-Four. While Winston struggles to remember life before Big Brother—everything, including the names of countries, had been different then (34)—he remains certain that London has always been London.

Join me for Migrating Words, UCL Culture’s creative writing workshop examining London, Orwell, and the works of the UCL Art Museum collection.

Close

Close