Museum Engagement Outside the Museum

By uctzcbr, on 9 October 2018

On a recent shift in the Grant Museum , I was talking to a small child about the bats. I explained that some bats will eat twice their own body weight in fruit in a single night. I like to share this fact with kids because I then ask them to imagine eating twice their own body weight in their favourite fruit and they are often extremely impressed (an opinion I think everyone should have of bats all the time). On this occasion, I asked the child how much he thought twice his own body weight would be in his favourite fruit – cherries. He turned to his mum and asked her how much he weighed (17kg), he then patiently counted twice 17 out on his fingers and before replying, very seriously, “it would be 34kg in cherries”. I have been telling this fact to visitors, I estimate, for probably 3 years now. This is the first time anyone has calculated an answer to my follow-up question.

Needless to say, I was impressed, and also touched by how proud this boy’s parents were. Moments like these are one of many reasons I really enjoy speaking to children who visit the museums. They are like small sponges (so right at home at the Grant) and filled with questions that vary wildly and wonderfully from the collection (my favourites include “is everything really dead?” and “how did he brush his teeth?”).

Whilst searching for a suitable image for this post, I discovered the Sponge Crab. This species of crab, that wears sponges as a hat, is an even better metaphor for children because it scuttles. (Image: Grant Museum)

The interesting conversations and literal hours of fact swapping with young visitors that I have enjoyed on my shifts are why I always enthusiastically volunteer to go on school visits and why, last week, I paid a visit to Fleet Primary School to talk to their students for Maths Week.

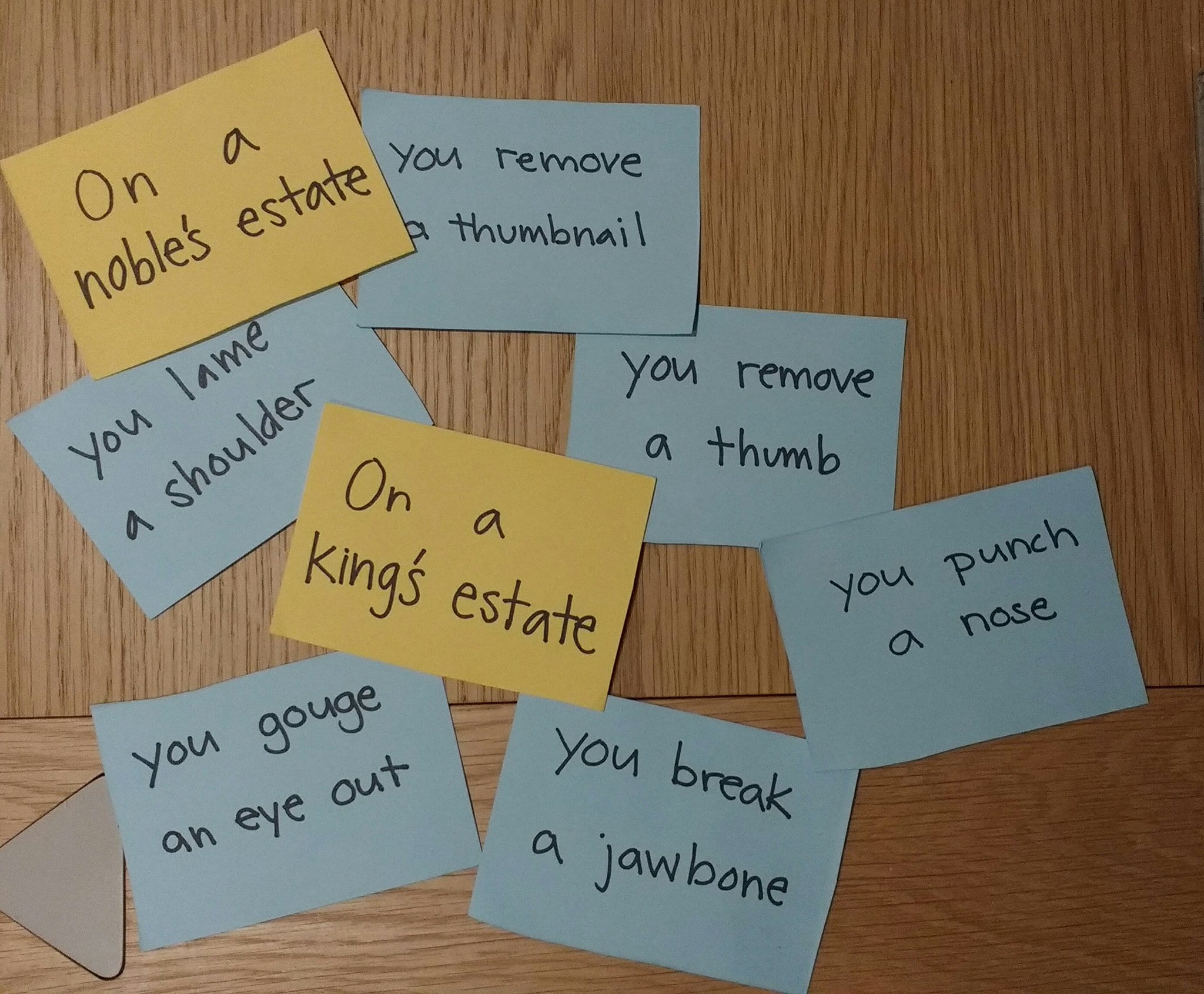

I was there to talk to the students about my research (in the UCL Crime Science department ) as an example of a something you could do if you studied maths. We talked about the different ways I use maths to understand Dark Net Markets (websites only accessible by anonymity preserving technologies such as Tor that facilitate the trade of illegal goods and services) and how it was similar to the maths they are learning in school. A lot of my research involves trying to measure the population size on these websites and evaluate if it’s been affected by a law enforcement intervention, so it’s basically adding and subtracting. I also look at the proportions of different types of products available to purchase; or, in other words, I divide things.

You may think that my research area is not an appropriate discussion topic for 8-11 year olds but, as ever, I was surprised by how much the students already knew. A good handful of them had heard of the Dark Web, some even knew about the types of the illegal purchases that could be made on it. Fewer had heard of the ways that the Dark Web is used by human rights groups, activists and whistleblowers to circumnavigate censorship and share information that might endanger them. Even though my research focuses on the illegal activity enabled by the Dark Web, a huge benefit of the outreach I am able to do with UCL is the opportunity to inform people about how important a space it can be. Plus I get to hear all of the insightful and interesting thoughts that the students I meet have about my research and being safe online.

The main role of the student engager is to hover in one of UCL’s museums and engage (ensnare?) visitors with conversations about the collections and our research. It takes a bit of getting used to – approaching strangers enjoying their lunch break or afternoon out and interrupting their visit with questions like “what do you think of the skeleton?”, “would you like to hear more about the history of this museum?” or “have you seen the bats?”, but it is a really interesting way to talk to people with lots of different lives and opinions about what happens at UCL. Sometimes, however, we get to take this conversation outside of the museum and learn a lot more about the people we talk to. It’s similar to the work we do in museums, but on a bigger scale, which allows for even more ideas to be shared. I really enjoy this part of the job, especially because I get to do the interesting talking-to-people part without the having-to-initiate-a-conversation bit.

Close

Close