Art in History: A Representation of Reality or Political Tool?

By Gemma Angel, on 5 November 2012

by Sarah Chaney

by Sarah Chaney

During the recent One Day in the City exhibition in the Art Museum, I had an interesting conversation with a couple of visitors who had popped in during the Marxism 2012 conference held elsewhere onsite. The exhibition took a variety of images depicting certain aspects of London over time, often raising questions about the relationship between representation and reality: for example, an etching showing the city as if viewed from a non-existent hill. Prior to aeroplanes, helicopters and even hot air balloons, the artist could not possibly have seen the city from such an angle. Yet they imagined what such a view might have looked like, and faithfully drew their idea of the reality.

By situating such images in the past, we often assume that we are seeing uncomplicated depictions of reality: what life was really like in London a hundred, two hundred, or three hundred years ago. Yet representations of London life are just that: representative of a particular individual – and, most often, social or political – point of view. When we look at historical prints as objects, stripped of their context – and even their creators – we run the risk of misinterpreting them altogether.

“Do you think?” one of the visitors mentioned above asked, “that time often causes us to dilute, or even lose altogether, the political message of historical images?” This conversation encouraged all of us to view the exhibition in a slightly different manner, looking beyond what we could recognise of “our” London (buildings, geographical landmarks or institutions) to see London as a place teeming with people who were, genuinely, historical actors: people who held diverse beliefs, opinions and ideas just as we do.

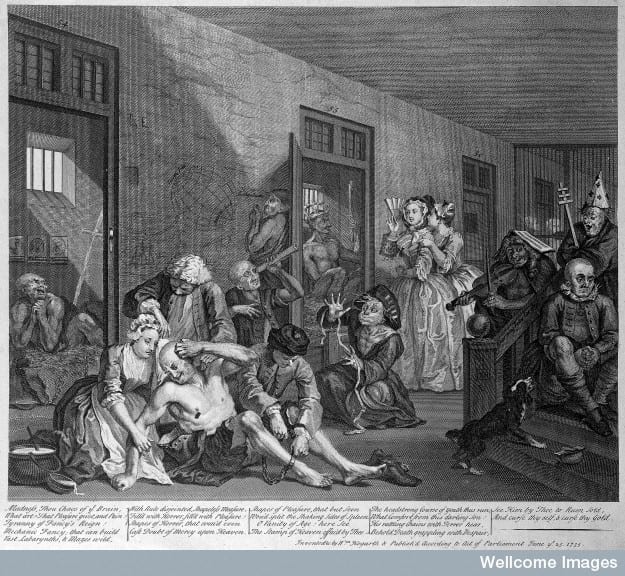

In particular, we discussed some of the etchings by William Hogarth displayed in the exhibition. It is well known today, of course, that Hogarth (1697-1764) was a satirist and social critic. His works often run in a series, charting the course of particular ways of life that he wished to critique: on display in the museum was Industry and Idleness: other examples included Marriage à la Mode and A Rake’s Progress. Despite acknowledging the critical nature of Hogarth’s work, and the strong use of symbolism within his images, scenes of London life are nonetheless often assumed to be just that: a clear representation of what life was actually like in the city during Hogarth’s life. Nowhere does this occur more frequently than in relation to the final scene in A Rake’s Progress, in which Tom Rakewell’s profligate life has seen him admitted to the “madhouse”: the Bethlem Royal Hospital (or Bedlam, as it was commonly known).

Hogarth’s image of “Bedlam” is often used in histories as an illustration of the eighteenth-century asylum, suggesting that various elements of the work indicate what the asylum was “really” like at the time. In particular, the well-dressed lady visitors are used to highlight the existence of public visiting in this period, a regular practice until 1770. Like most hospitals in this period, Bethlem was a charitable institution and thus was maintained by donations, which were requested from all visitors. Yet Hogarth’s image is a satire: while Rakewell’s fellow patients can be viewed in relation to diagnoses of the day (such as religious delusion, love melancholy and delusions of grandeur), they can equally be seen to satirise the state of contemporary institutions – the Church, the monarchy, and scientific endeavour. By viewing Hogarth’s image merely as a representation of the Hospital itself, we risk missing the fact that he also has plenty to say about society outside the Hospital. As in drama, literature and poetry, representations of Bethlem in art frequently aim to hold a mirror up to society, rather than to represent the realities of mental health experience and treatment.

Close

Close