How Did Man Lose His Penis Bone?

By Suzanne M Harvey, on 26 November 2012

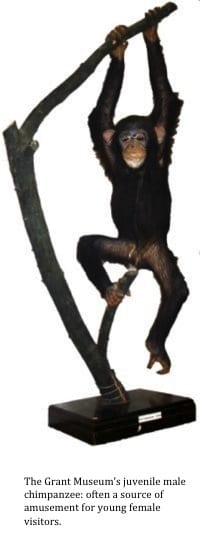

The walrus penis bone, also known as an os penis or baculum, is one of the most popular objects at the Grant Museum. The human penis is haemodynamic, meaning an erection is achieved by blood pressure alone. In animals with an os penis, blood pressure still plays an important role, but the pressure functions to push a bone structure into the penis in order to achieve an erection. This has many benefits over an erection sustained by blood pressure alone, not least in keeping the glans open for sperm to pass through.

While the importance of shaft size and sperm competition has been discussed in my previous blog post, even the largest penis will offer no evolutionary advantage if sperm cannot escape: these much desired qualities will never be passed to offspring. This is not the only benefit. The os penis increases the potential duration of intercourse and also the frequency with which intercourse can take place. For example, a lioness can copulate 100 times per day, sometimes with only four minute intervals, but has only a 38% conception rate1 – males need to keep up if they’re to achieve the best chance of paternity. It comes as a surprise to many people that the os penis exists at all, but in fact humans, woolley monkeys and spider monkeys are the only primates to lack this handy piece of anatomy.

With such benefits to structure, strength, endurance and recovery time, the next question must be: where is man’s penis bone? This is where the story becomes more intriguing…

With such benefits to structure, strength, endurance and recovery time, the next question must be: where is man’s penis bone? This is where the story becomes more intriguing…

Was it sacrificed for the sake of woman?

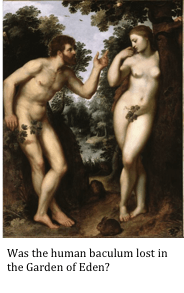

While the lack of a human penis bone may have interested evolutionary scientists for many years, it has recently attracted attention from professors of Theology as well. The debate was reignited in 2001 with the publication of a letter entitled Congenital human baculum deficiency: the generative bone of Genesis 2:21-23. Without wishing to delve into a religion vs. science debate, perhaps the most surprising aspect of this article is that it was published in the American Journal of Medical Genetics, with its central theory that God took Adam’s os penis to create Eve in the Garden of Eden, rather than his rib:

Ribs lack any intrinsic generative capacity. We think it is far more probable that it was Adam’s baculum that was removed in order to make Eve. That would explain why human males, of all the primates and most other mammals, did not have one.2

The authors then go on to cite possible mistranslations of the Hebrew word ‘tzela’, which can be translated as ‘rib’ or more generally as a supporting structure such as a baculum. More recently however, a study using the dissection and microscopic analysis of human, dog and rat penises revealed something rather unexpected…

The authors then go on to cite possible mistranslations of the Hebrew word ‘tzela’, which can be translated as ‘rib’ or more generally as a supporting structure such as a baculum. More recently however, a study using the dissection and microscopic analysis of human, dog and rat penises revealed something rather unexpected…

Perhaps it was there all along!

With the comprehensive list of benefits discussed above, the root of this problem seems to be in discovering how on earth humans manage to function without an os penis. As a rule, larger penises in humans can give an evolutionary advantage, but without the toughness of structure provided by a bone, how do they avoid buckling under the pressure? Well, through both microscopic analyses and collagen tissue staining, the elusive evidence has finally been discovered. In the core of the human penis, there is a tunica (or lining) with many elastic fibres acting to keep the penis rigid in much the same way as an os penis. This has been referred to as the distal ligament, and is a structure so robust that even after some venous removal, erection can still be achieved without the need for a fully formed bone structure.4 In somewhat less good news for men, the authors of this study further hypothesise that if damaged, the distal ligament may take as long as a broken bone to heal.

So we are left with the final puzzle of why man lost his penis bone but retained a structure that serves a similar purpose. For the answer to this, we may need to look to women. Sexual selection works on the premise of ‘honest signals’. Put simply, females need to select high quality males to ensure the best genes for their offspring, and a penis that works predominantly through haemodynamics takes a lot of energy to produce. Therefore this is an honest signal of the most healthy males in the same way that the healthiest stags grow the largest antlers. In the end, for all the dissection, microscopic analyses and experiments with cadavers, Adam may have given up his penis bone for Eve after all.

Suzanne Harvey is a PhD student in Biological Anthropology, working on social interactions and communication in wild olive baboons. She is also a teaching assistant on the UCL Arts and Sciences BASc, a new interdisciplinary degree, and can be found on twitter @suzemonkey.

References:

1. Rudnai, J. A. (1973). Reproductive biology of lions (Panthera leo massaica Neumann) in Nairobi National Park. East African Wildlife Journal II: 241 – 53.

2. Gilbert, S. F. & Zevit, Z. (2001). Congenital human baculum deficiency: the generative bone of Genesis 2:21-23. American Journal of Medical Genetics 101(3): 284-5.

3. Hsu, G. L., Lin, C. W., Hsieh, C. H., Hsieh, J. T., Chen, S. C., Kuo, T. F., Ling, P. Y., Huang, H. M., Wang, C. J., & Tseng, G. F. (2005). Distal ligament in human glans: a comparative study of penile architecture.Journal of Andrology 26(5): 624-8.

4. Hsieh, C. H., Liu, S. P., Hsu, G. L., Chen, H. S., Molodysky, E., Chen, Y. H., Yu, H. J. (2012). Advances in understanding of mammalian penile evolution, human penile anatomy and human erection physiology: clinical implications for physicians and surgeons. Medical Science Monitor 18(7): 118-25.

Close

Close