Question of the Week: How did men in antiquity shave?

By Lisa, on 19 February 2014

By Felicity Winkley

A visitor to the Petrie Museum recently asked me how the Egyptian working class men would have shaved. There are various razors in the Petrie collection, including UC40657, a copper alloy razor with a loop in the shape of a goose head, and UC3065A and B, two copper alloy razors from Saqqara, the principal cemetery in Memphis; the oldest recorded on the Petrie’s resource Digital Egypt date to the Old Kingdom, around 2686-2181 BC. But would the working classes have had access to metal blades like these? And if not, would they have found an alternative way of shaving?

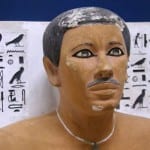

As with much of the archaeological record – particularly where we rely upon contemporary written or art-historical accounts of societies – the working classes are under-represented in favour of the material cultures of the elite. In dynastic Egypt, we know from artefactual and art-historical evidence that the elite devoted a lot of energy to maintaining their appearance, with laborious cosmetic routines, and even curled their hair. By contrast, the priestly classes were often totally clean shaven, taking a razor to their bodies as well as their heads. Rahotep, an official during the Third Dynasty (around 2600 BC), is unusual in being pictured on official statuary sporting a moustache, some 5000 years before Movember was established!

But would everyone have had access to metal razors? It is widely acknowledged that there were professional traveling barbers working in ancient Egypt, so perhaps this was how most men were able to keep their beards trimmed, either by being visited by a barber or attending a barber’s shop, rather than owning their own personal razor.

For evidence of practices amongst those without access to metal, it might be useful to look at contemporary ethno-archaeological evidence from tribal communities, however the records are sparse. Flint or obsidian tools would have been an option should Stone Age man have wished to remain clean-shaven, and the fact that – as with most blades struck from a prepared core – they would have needed to be discarded after only a few uses puts me in mind of the disposable razors used by many today! Meanwhile, Roman textual evidence suggests plucking was an option for some men, perhaps used in combination with an exfoliant, as suggested in Martial’s Epigrams 9.5.4. in which he describes a male wine-server who his master wishes to be ‘kept a boy even though he is a man …who is kept beardless by having his hair smoothed away or plucked out by the roots’ (cited George 2002).

Lastly, we should return to the Petrie collection, in reference to UC40665 – a razor which has been interpreted as a ladies’ razor, with a handle shaped like the hippo goddess TaWeret, who represented childbirth and fertility. Evidently shaving was also considered a part of the cosmetic routine for women in ancient Egypt as well as men, and any consideration of the role of shaving in ancient society should not overlook them!

Cowley, K. and Vanoosthuyze, K. (2012) Insights into shaving and its impact on skin, British Journal of Dermatology 166 (Suppl. 1) pp. 6–12

George, M. (2002) Slave Disguise in Ancient Rome, Slavery & Abolition: A Journal of Slave and Post-Slave Studies 23 (2) pp. 41-54

Close

Close