Women and Beads: Ancient Egypt to the Jamestown Colony

By ucramew, on 15 March 2016

By Misha Ewen

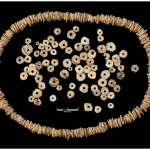

The ‘bead net dress’ is one of the Petrie Museum’s Top 10 objects and one that visitors are always excited to see. It struck me when I started working in the Petrie as a Research Engager just how many beads there are in the collection. There are numerous bead necklaces on display around the museum walls, as well as more beads in the display cases. It made me think of my own research, which touches on the history of the English colony in Jamestown, North America, and how beads had an important function in colonist-Amerindian relations.

Beads at Jamestown

English colonists, who were backed by the Virginia Company, landed at Jamestown in 1607. There they encountered the Algonquian-speaking Amerindian Powhatans who they hoped to trade. They also wanted to learn from them the location of gold mines. There was no gold, but they did trade with them for corn. In these exchanges beads were fundamental. Hundreds of beads have been excavated from the Jamestown fort including those manufactured in Venice and brought to Virginia by English colonists. Many of the beads are blue in colour, ‘a desirable trade item to the Virginia Indians who, according to reports, highly valued beads that were the color of the sky’ [1].

Beads continue to inform research at the Jamestown fort. Archaeologists have found almost 2,000 mussel shell beads that were crafted from ribbed mussels, or tshecomah, that lived in abundance in the marshes around Jamestown. Amerindian women worked these beads, breaking them into small pieces (called perew) and then into semi-round disks. Then they bore a hole in the middle with a stone drill (a mananst). These beads were crafted until they were a similar size and shape by stringing and abrading (to rub, scrape or wear down) them on rock.

Archaeologists at Jamestown suspect that these beads, which were symbolic items of exchange in Powhatan marriage ceremonies, might suggest not only that Amerindian women were living in the English settlement, but that these beads may have been prepared to recognise the marriages of English men and Algonquian women (something that written records from the time are largely silent on). Aside from a letter written by the Spanish ambassador in London to his king in 1612, who claimed that 40 or 50 Jamestown settlers had married native women, we know little else (and his report is not completely trustworthy) [2]. Therefore, the beads provide the strongest evidence yet of the place of Amerindian women in the colonial fort.

Transatlantic Bead-Obsession

Between September and December 2015 I spent time as a visiting researcher at Yale University, which allowed me to have the amazing opportunity of visiting the Jamestown site in Virginia. There I was welcomed by staff in archaeology who kindly gave me a behind-the-scenes tour of the collections and site. Being there really opened by eyes to how knowledge about life in the colony is constantly being reshaped by archaeological discoveries (mostly by items that were ‘thrown away’ by settlers). In particular, I was fascinated that these new finds will open windows into our understanding of the role of women in the colony — both European and Amerindian.

On my trip I also had the opportunity to spend time in some amazing museums and galleries: the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Yale University Art Gallery, MOMA (New York) and during a trip to Chicago for a conference in June, the Art Institute of Chicago — all rank as world-class collections. By far my favourite find in these collections was related to beads: an Egyptian bead dress in the Boston Museum.

This dress caught my eye because of its similarity to the much beloved bead net dress in the Petrie collections. On Twitter, my post about these two dresses (the one in the Petrie and the one in Boston) received a lot of love: 21 retweets and 32 ‘loves’. (N.B. the Boston Museum also has another Egyptian bead dress in its collection.)

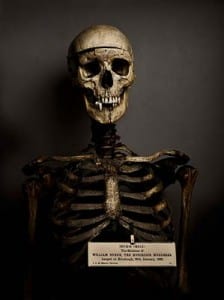

Egyptian Bead Dresses

The dress in the Boston Museum was found in the tomb of a woman, excavated in Giza in 1927. Its function as a funerary garment required it to cover only the front of the body. The beads on the dress were originally blue and green, in imitation of lapis lazuli and turquoise — much like the beads found in Jamestown. If similar styles of dress were worn in everyday life they may have been pulled over an under-garment. Indeed, scholars have found representations of bead net dresses in ancient Egyptian reliefs and statues, and there was a famous tale of King Snefru’s oarswomen dressing themselves in netting. Dresses of this type were familiar, and many more women who died during the Old Kingdom probably wore them at burial [3].

The bead net dress in the Petrie Museum was excavated from Qau in 1923-4. At first, those who studied the dress thought that it had probably been worn by a dancer: according to the Petrie’s website, ‘the 127 shells around the fringe are plugged with a small stone so that it would have emitted a rattling sound when the wearer moved’.

When a replica of the dress was made, however, specialist clothing consultants found that the dress was too heavy to be worn on a naked body. This research gives credence to the idea that the dresses were primarily funerary, rather than dance or everyday, wear [4]. Unfortunately, this reading removes some of the more erotic associations that have been afforded the bead net dresses…

When I returned from my trip and visited the Petrie Museum (and the bead net dress), the importance of material culture – particularly for studying the lives of individuals who are largely silent in the historical record – was reinforced. Material culture and archaeology is increasingly integrated by historians in their work, but I would call for even more interdisciplinary – especially when we are trying to understand the lives of individuals who were marginalised in the past and remain so in scholarship.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Merry Outlaw, Curator of Collections at the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, for giving me a tour of the collections and enlightening me about women and objects in the colonial Jamestown fort.

Further reading:

Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, ‘Selected Artifacts’, http://historicjamestowne.org/collections/selected-artifacts/ [accessed 14/03/2016].

Petrie Museum, ‘Bead Net Dress’, http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie/about/collections/objects/bead-net-dress [accessed 14/03/2016].

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, ‘Beadnet dress’, http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/beadnet-dress-146531 [accessed 14/03/2016].

Boston Museum of Fine Arts, ‘Beadnet dress’, http://www.mfa.org/collections/object/beadnet-dress-315900 [accessed 14/03/2016].

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids (New York, 1999), pp. 306-7.

Close

Close