Stress: Selecting and Engaging with Pathology Specimens in the Exhibition Space

By Sarah Savage Hanney, on 28 October 2015

By Sarah Savage Hanney

Over the past two and a half weeks, I have had the pleasure of engaging with visitors in the Stress exhibition at the North Lodge. When visitors first come into the space, many ask questions about the concept behind the exhibition and the selection of objects. In the planning process, each exhibition curator chose objects from the UCL Collections that related to his/her approach to stress in the First World War and significance within individual PhD research.

When the Student Engager group first discussed curating an independent exhibition using UCL Collections objects and specimens in summer 2014, I already knew exactly what collection I wanted to use: the Pathology Collection. Unlike the three UCL Museums on campus, the Pathology Collection was less accessible to the public due to human tissue licensing restrictions. For the previous Engager event Movement in May 2014, I used photographs of Pathology specimens to enhance visitors’ understandings of the effects of disease on the human body. Visitors were especially interested in the photographs of a coal miner’s lung, diseased human heart, and a haemorrhaged brain. I kept these interesting specimens in mind and hoped to use them in our future exhibition.

Luckily, the Pathology Collection received its license to display human tissue early in 2015 and it would be possible to display Pathology specimens in the Stress exhibition. The curator of the Pathology Collection, Subhadra Das, was incredibly helpful in suggesting specimens and organising the conservation work for the two final selections: the coal miner’s lung and the diseased human heart.

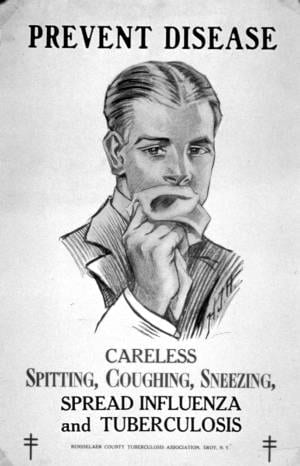

Visitors can now see the coal miner’s lung and diseased human heart suspended in a clear, preservative liquid on either end of the long wall display in the exhibition space. As a historian of medicine specialising in the early twentieth century, I wanted my contribution of specimens to highlight little known medical conditions that affected people in the First World War period.

Although we do not know specific dates for these specimens, the organs came from patients at University College Hospital in the first half of the twentieth century.

At first glance, the specimens can be a bit off putting. The coal miner’s lung barely looks like a lung apart from the general shape. The lung is nearly completely black and exposes the harsh reality of the health of British coal miners. For those men who remained in Britain mining coal for the war effort, their efforts would eventually cost them their healthy lungs.

The diseased human heart also holds special significance for health in the First World War period. Over the course of the war, the British military medical officers discovered that many young men who enlisted to fight had pre-existing heart conditions that would affect their ability as fit, healthy soldiers. After speaking with visitors about this specimen, many visitors commented on how they never associated heart disease with the early twentieth century.

By having these specimens on public display, I hope that visitors contemplate the stress that the First World War placed on the physical bodies of those who fought and contributed to the war effort. The exhibition presents a rare opportunity for visitors to examine these remarkable specimens in person and engage in discussion with curators about their different approaches to stress in the First World War.

If you are interested in speaking with Engager Sarah Savage Hanney in the exhibition space, she will be at Stress each Friday from 1pm-5pm for the next three weeks.

Stress is open Monday through Friday from 1pm-5pm and on alternating Saturdays.

For more information about visiting the UCL Pathology Collection at the Royal Free Hospital Campus of the UCL Medical School.

Upcoming Events:

Commemoration Event, November 11, 2015 1pm-3pm UCL Art Museum

Bloomsbury Walking Tour, November 20, 2015 1pm-2pm UCL Quad

Close

Close