An Afternoon with Materials & Objects

By Arendse I Lund, on 25 May 2017

Materials & Objects, an afternoon of short talks by UCL’s student engagers, took place on Thursday, 18 May 2017, in the UCL Art Museum.

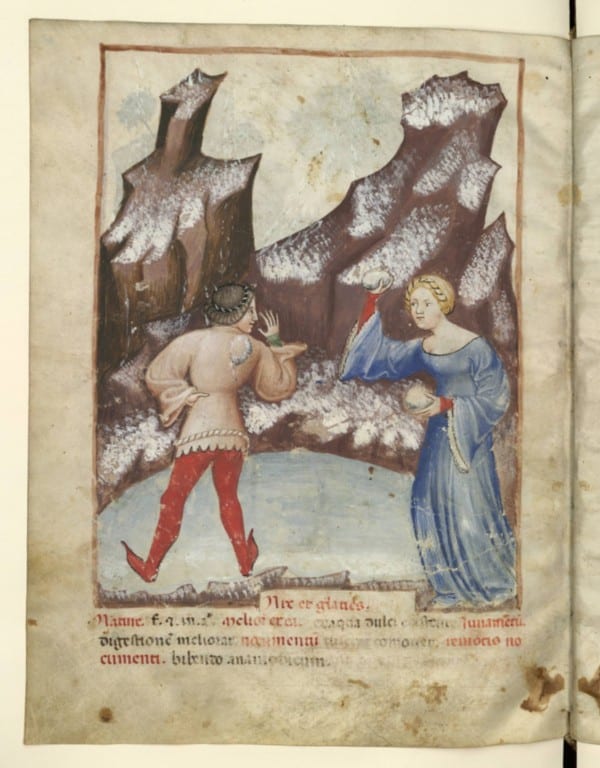

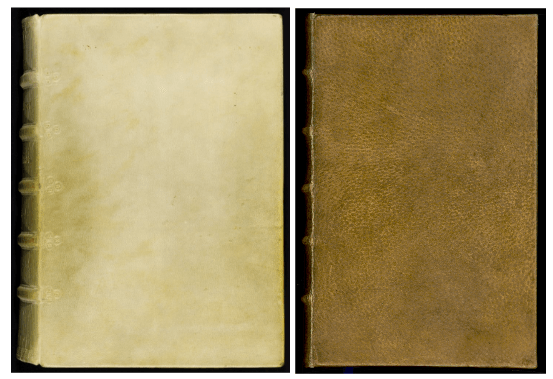

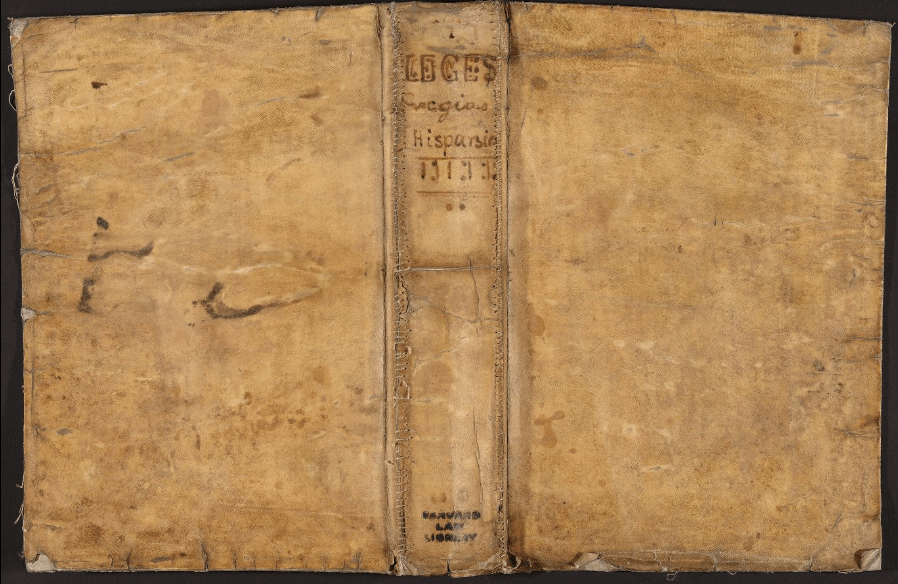

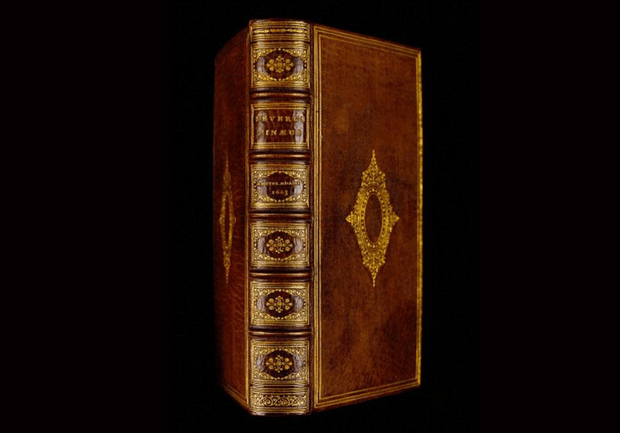

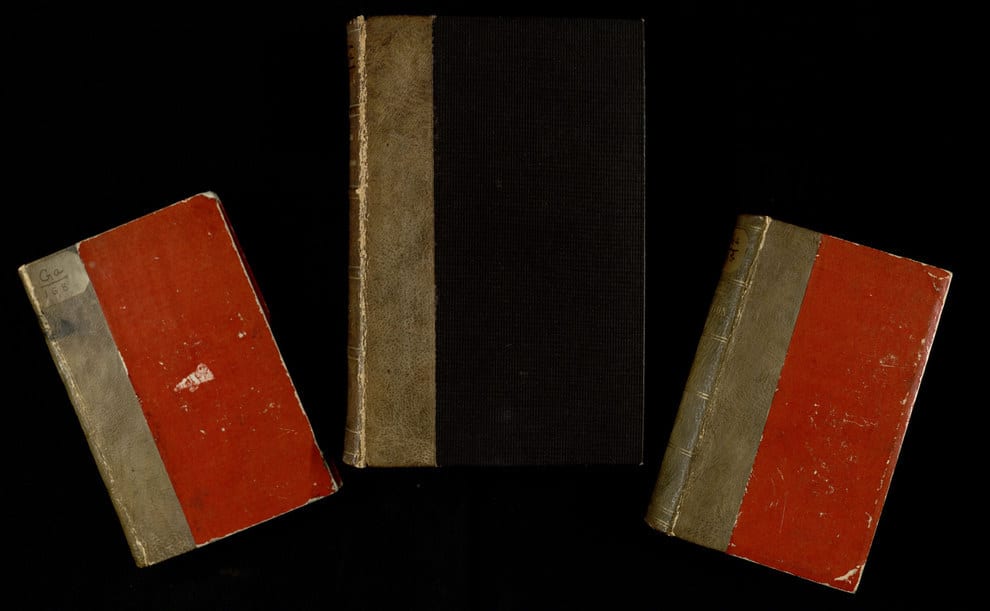

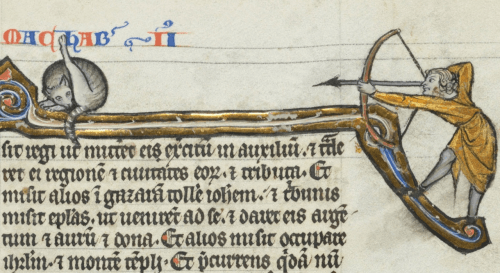

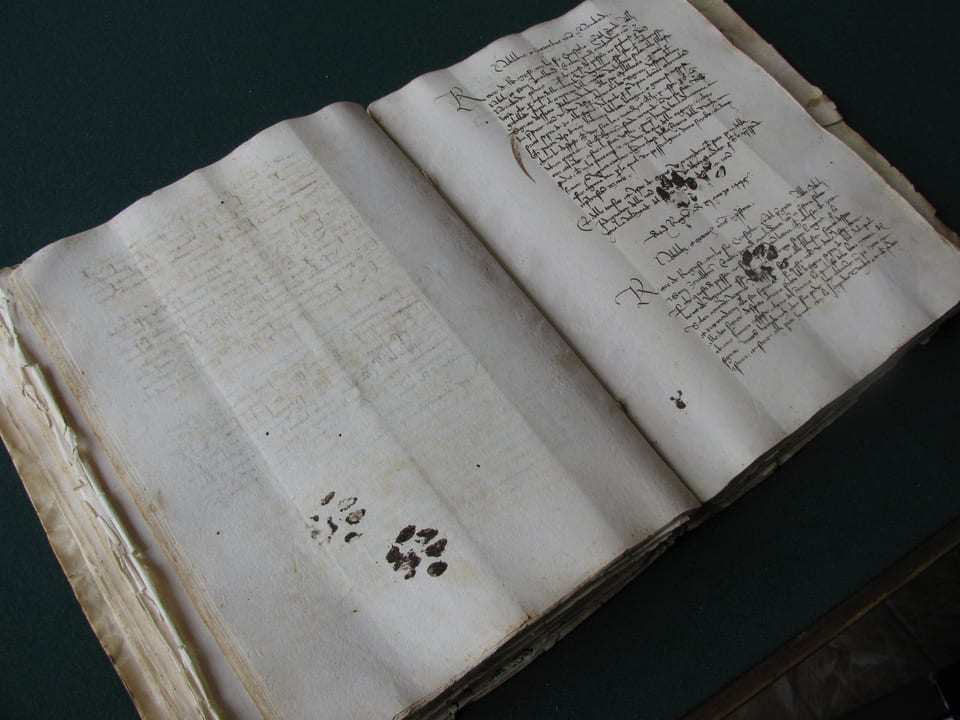

The first manuscript I ever handled was the Vercelli Book. I was on an archival research trip to the Capitulary Library of Vercelli, just outside of Milan, and I couldn’t believe that the librarian would entrust me with this. Awe struck and fangirling, I oh-so-very-carefully flipped my way through the large manuscript. I had written papers and looked at digital versions of the manuscript but nothing could compare to handling and studying it in person.

The Vercelli Book is a late 10th-century work, compiled of both prose and poetry, and written in Old English on parchment. How it got down to Vercelli is still something scholars debate. It’s not the largest work I’ve ever handled, and depending on your perspective, not the rarest either; I’ve handled manuscripts that are technically saints’ relics. The Vercelli Book holds a special place in my heart and I’ve never lost my awe for handling the objects behind my research.

Talking about the manuscripts with the public is one way I try to share my enthusiasm for what an incredible field of studies I’m in and how exciting it is to be a medievalist. Last week’s Materials & Objects event was the first event we’ve put on since I’ve joined the fabulous Student Engagement team here at UCL and one in which I got to speak all about manuscripts and what they’re made of. Thanks to everyone who turned up, the UCL Art Museum was packed — we even had to place out more chairs! — and the presentations sparked fascinating questions about aspects of research that showed everyone was really engaged with the speakers.

In a way it’s humbling to hear about all the incredible and life changing research that my fellow PhD students are performing. Hannah took the audience step-by-step through recreating the process of 18th-century paper making in her kitchen, and Kyle talked about depictions of archives and their diversity problems (something he’s also written about on this blog). Cerys spoke about researching the Dark Web to aid law enforcement, and Citlali walked the audience through the difficulties and possibilities of growing brains in labs. Josie defended Neanderthals (something she’s done here as well) and handed around flint examples for everyone to feel; finally, Stacy subtly gave the concluding talk standing on one leg to demonstrate how our day-to-day activities shape our bone growth.

Thanks to everyone who came out and participated in our event — leave us a comment and let us know what you thought. If you missed the afternoon, don’t fret; many of the talks will appear in blog post form here before too long and you’re always welcome to come into any of the UCL museums and talk to us more in person!

Close

Close