Breaking down barriers to student engagement: our co-production workshop

By Blog editor, on 14 December 2021

Post by Susie Haynes, Clinical Psychologist, previously on placement as a trainee with PsychUP for Wellbeing from October 2020 – March 2021 (historic post from Spring 2021).

Reading Time: ~ 3 mins

Susie Haynes reflects on a fruitful workshop aimed at improving PsychUP for Wellbeing‘s student engagement strategy. Carry on reading to check out our team’s shared formulation of some of the facilitators and barriers to co-production.

As a Trainee Clinical Psychologist on placement at PsychUP for Wellbeing, I was delighted to facilitate some co-production workshops for the programme team and student members of the Advisory Board – and I want to start this blog post by thanking all the students gave their valuable contributions to these discussions.

Our workshops began with the question: How can we increase participation across the student population, so that more voices can be heard?

PsychUP for Wellbeing aims to increase participation from students so that all of our projects appeal to students, represent their experiences and are effective in targeting the issues they face. Students bring passion and insight to our work, so, naturally, we want more of their help! Follow this link to see how you can get involved.

Developing a shared understanding

As a starting point, we thought it would be important to develop a shared formulation1 of the factors associated with student engagement. Within group discussions, we established possible motivators, benefits, barriers and costs of co-production for students.

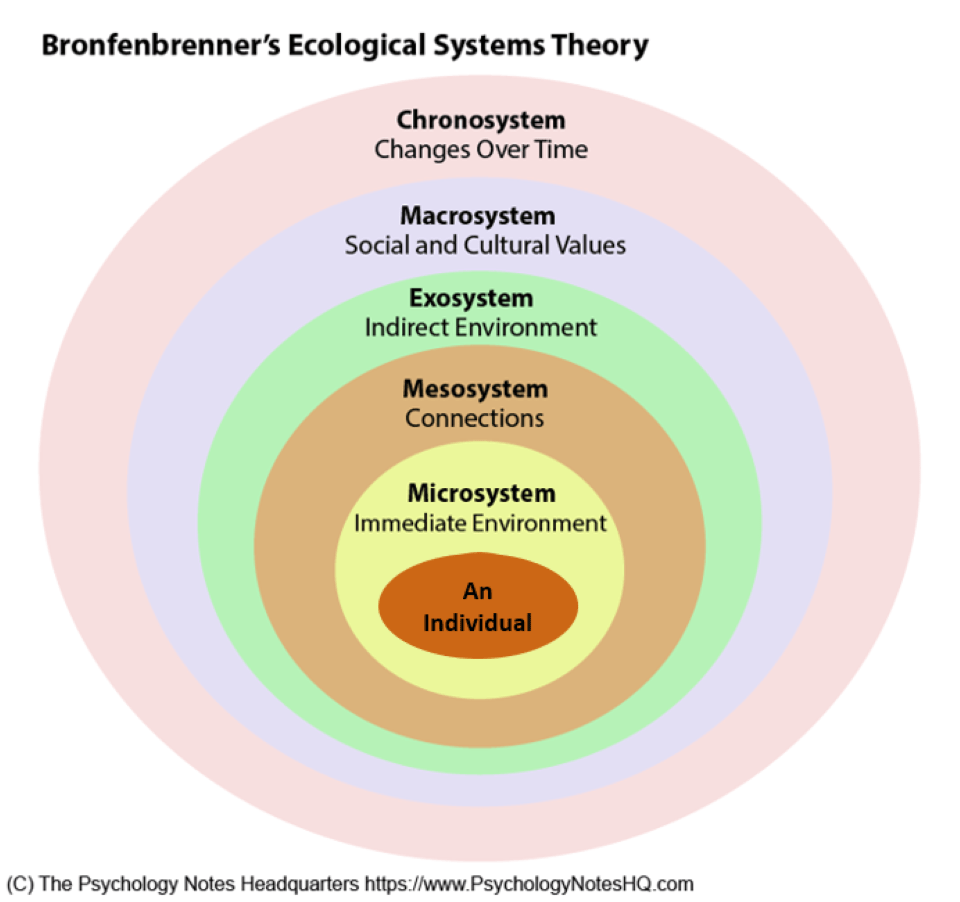

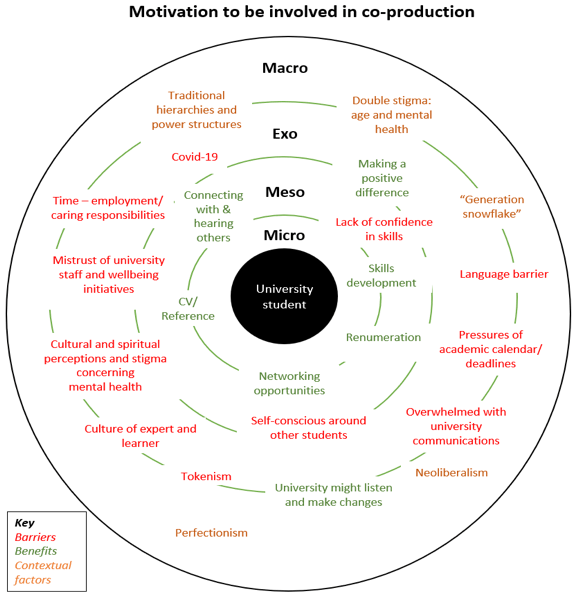

By drawing upon principles of systemic theory, I mapped our ideas onto the Ecological Systems Theory framework2, which can be seen below:

New perspectives

Many of the incentives currently offered to students to encourage engagement in co-production appeared to be aimed at individuals (for example, personal skills development, references, support for CV, remuneration). We noticed this contrasted with many of the barriers the team had identified, which existed at the wider environmental levels (such as stigma, lack of time and caring responsibilities).

Many of the incentives the team identified appeared to be aimed at individuals, whereas many of the barriers existed at the wider environmental levels

A new perspective was opened up by our discussions and we agreed it was important to reach out to student groups and communities to break down some of the barriers to getting involved. We discussed communicating through different virtual and real life spaces to contact students where they feel comfortable, e.g. student societies.

We were really excited to share our team formulation with the student members of our Advisory Board, to check if this understanding matched their experiences.

The student Board members agreed with our formulation and some were able to personally relate to some of the barriers listed, including perceived lack of confidence and skills and worries around challenging an ‘expert’ culture. They also reflected on how mental health is perceived and stigmatised in many cultural, spiritual and religious backgrounds and how this can act as a significant barrier to engagement.

Next steps

These initial conversations were really rich and thought provoking, and the student Board members had lots of ideas for how to engage students in the future – including open forums on our website, increasing visibility, co-produced advertisement methods and more informal communication methods. They are currently working on building these changes into our updated programme co-production strategy. Look out for future updates on this blog!

References

Close

Close