Interdisciplinary research, volcanoes and a travelling rhinoceros

By rejuhll, on 14 September 2015

Last week, the Division’s Qualitative Researchers Working Group co-hosted the first in a series of seminars on qualitative health research[1]. The theme was “interdisciplinary research” and the context, strangely enough for a division of psychiatry, was volcanoes. During the seminar, Anthropologist, Professor Linda Whiteford, and geoscientist, Professor Graham Tobin, both from the University of South Florida, shared tales of their long-time collaboration in Baños, Ecuador. Beyond jokes that they stood paralysed between Linda’s anthropologically-informed worry about eating local vegetables customarily soaked in water that was likely to carry disease, and Graham’s geoscienfically-informed fears that the volcano could quite literally blow a hole in their research at any moment, their thesis was a serious one: interdisciplinary work offers that which work confined to one or other discipline cannot.

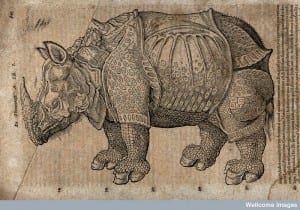

An écorché figure, front view, with left arm extended, showing the bones and the fourth order of muscles, with a grazing rhinoceros in the background. Line engraving by J. Wandelaar, 1742 (Wellcome Library no. 565796i)

Such a view is clearly etched into UCL’s Grand Challenges and underscored in the missions of research councils and an expanding population of interdisciplinary journals. It is seen as the latest iteration of the cutting edge in research planning, altogether more innovative, more relevant and more persuasive. Yet what does it really mean for projects to be interdisciplinary? How should we judge their successes? And how should a dynamic be set that allows each discipline to flourish according to its own terms?

Working across boundaries is by no means something new. A familiar example is that which gave birth to those images we see in textbooks and atlases and pore over in encyclopaedias. Images given in divine splendour towards an ideal type, which might not have followed the rough contours of the natural world yet which survived in the archetypes that became the basis on which the natural world was known. Here, the leaves of trees were cast as pure and unblemished, animals ennobled with human character, and human bodies turned inside out, made free of the sticky fluids that give them their fleshy corporality. Here is where we see draughtsmen working alongside botanists, zoologists, anatomists and surgeons.

An écorché figure, back view, with left arm extended, showing the bones and the fourth order of muscles, with a rhinoceros seen in the background. Line engraving by J. Wandelaar, 1742 (Wellcome Library no. 565802i)

A wonderful example is the Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani, published in 1747 by the Dutch anatomist Bernhard Siegfried Albinus. As well as giving us some of the most startlingly beautiful images of human anatomy, the Tabulae sceleti promised to rework concepts of the body into a reality hitherto unseen. To render this ambition, Albinus recruited Jan Wandelaar, master painter and engraver, and lover, it turned out, of rhinoceroses. He wrote of their relationship: “And thus [Wandelaar] was instructed, directed, and as entirely ruled by me, as if he was a tool in my hands, and I made the figures myself.”[2] This seems to deny Wandelaar of any agency in the production of the figures. Yet, perhaps it is misleading.

Wandelaar himself suggested that his figures be placed in natural settings “to preserve the proper light of the picture.”[3] He took freedom to embellish his figures, depicting them against grand and glorious backdrops of classical scenes, buildings and the natural world. And in several of the plates appears the bizarre figure of that which had preoccupied his earlier engravings: a rhino. Putting aside any guesswork about narrative, which might take us on a wonderland-like misadventure, here perhaps was a way in which Wandelaar was able to serve himself and popularise his version of a rhino amongst his peers and beyond. It is certainly an image whose legacy remains as amongst the most accurate of early renderings of a rhinoceros, one that broke artists free of a slavish mimicry of Dürer’s (1515) fancifully scaly and armour-plated monster[4].

It has also been noted that the inclusion of the rhino (and other details behind the figures) contributed to the wide circulation and enduring quality of the Albinus atlas.[5] The atlas itself became a material that travelled across disciplines, finding homes in the bookshelves of anatomists and artists alike, and informing the trajectories of fields from human anatomy and surgery to zoology and figurative painting. Is this perhaps a marker of interdisciplinary success: the production of knowledge that can travel across borders and settle in various academic homes? Knowledge that is both difficult to classify in ordinary terms and which can bridge the gaps between silos? And is this something that we should aim for in our collaborations, whether they be between anthropologists and geoscientists, psychiatrists and sociologists, or epidemiologists and qualitative researchers? I’d say, yes to all three, tipping my hat to the travelling rhinoceros…

[1] Seminar series co-hosted with the UCL Department of Applied Health Research and the UCL Health Behaviours Research Centre.

[2] Albinus, Academicarum annotationum, libri I-VIII, lib. 1. Praef quoted in Choulant, L. 1920. History and bibliography of anatomic illustration. Translated and annotated by Mortimer Frank. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p.277.

[3] Albinus, Academicarum annotationum, libri I-VIII, lib. 1. Quoted in Choulant, L. 1920. History and bibliography of anatomic illustration. Translated and annotated by Mortimer Frank. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p.17.

[4] Ross MacFarlane. Object of the month: Human skeleton and young rhinoceros. 2011. Available at: http://blog.wellcomelibrary.org/2011/08/object-of-the-month-august-2011-jan-wandelaar-human-skeleton-and-young-rhinoceros/

[5] Linda Wilson-Pauwels. 2009. Jan Wandelaar, Bernard Siegfried Albinus and an Indian Rhinoceros Named Clara Set High Standards as the Process of Anatomical Illustration Entered a New Phase of Precision, Artistic Beauty, and Marketing in the 18th Century. Journal of Biocommunications, 35(1), 10-17.

Close

Close