Written by Sophie Adler-Wagstyl @sophieadler, MBPhD student and part-time post-doctoral researcher. Sophie did her PhD in the Developmental Neurosciences programme on neuroimaging of paediatric epilepsy. In her spare time she enjoys cycling and supporting Spurs.

PhDs can be challenging, involving tough tasks such as:

- Learning new methods from scratch

- Focusing only on one project and not being involved in small side projects

- Not being part of a team and feeling lonely

- Not knowing how to do something and being afraid to ask

- Being asked to review a paper and not knowing how

- Not being asked to review a paper but wanting to learn how

To address this, I helped to organise an open-science, reproducibility and teamwork session at Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (GOSICH) in October 2018. PhD students and post-docs spanning the breadth of research at GOSICH came along to listen and learn. Despite the diversity of methods and areas of research that people focus on at GOSICH, we discussed that there are a lot of skills required for research that are common to all of us. Many of us:

- Have to learn stats and learn to code some of our analysis whether that be in R, Matlab, Python etc.

- Have to think about ethics, IRAS applications, HRA approval, the GOS-ICH R&D department

- Are doing longitudinal analyses

- Are peer-reviewing work for the first time

And there are many more areas of mutual overlap…

In the October session, we discussed many of these topics. The outcomes of these discussions are outlined below, grouped into the areas of: collaboration and teamwork, reproducible research, open-science and peer review.

Collaboration & Teamwork

Collaboration and teamwork can help address some of the problems that PhD students face, such as learning new methods from scratch, not feeling part of a team and not being involved in side projects. However:

- How can we create a collaborative and supportive environment where we can ask others for help?

- How can we make our research more efficient by not repeating what others have already worked on?

- How can we find potential collaborators?

To help with the challenges above, we have created a GOSICH SLACK workspace. This is an online space where members can post questions, events etc. and anyone from the community can respond. As well as a general channel, we have channels (groups) for early career researchers, a PREreview journal club, and social events. However, you can create a channel for anything, including for particular projects/topics, where you invite only your collaborators, a lab group, the post-doc society. If you are a current GOSICH PhD student or post-doc and would like to join the SLACK workspace, please email sophie.adler.13@ucl.ac.uk for more information.

Reproducible Research

We all want to do robust, reproducible, replicable and generalizable research. We want to know that our findings are real. We want the work to go beyond the lifespan of one PhD student or post-doc position and impact the wider scientific community.

So firstly, what is the difference between reproducible, robust, replicable and generalizable research?

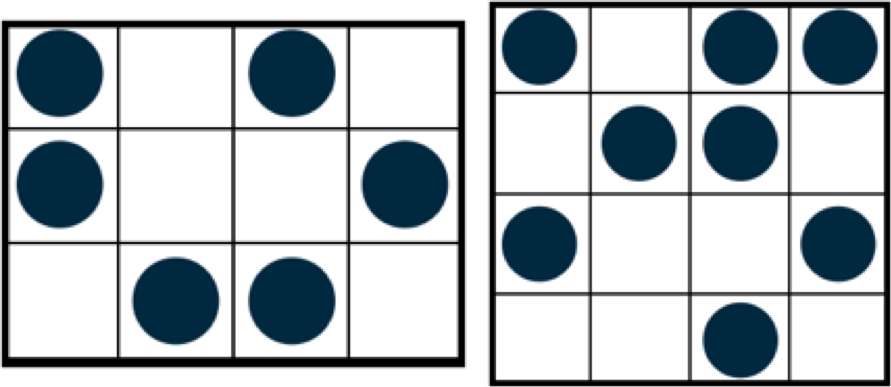

@kirstie_j has a handy figure to explain it! Feel free to replace the word ‘code’ to ‘method’.

If you test a hypothesis using the same method and same data as some-one else (including your previous work), and you get the same result, your research is reproducible.

If you test the same hypothesis with a different method on the same data and get the same result, the finding is robust.

If you test the same hypothesis and use the same method on new data and get the same results, your findings are replicable.

Lastly, if you test the same hypothesis with a different method and different data, your results are generalizable.

Open-science

We can use open-science techniques to facilitate reproducible, robust, replicable and generalizable research.

“Open Science is the practice of science in such a way that others can collaborate and contribute, where research data, lab notes and other research processes are freely available, under terms that enable reuse, redistribution and reproduction of the research and its underlying data and methods.” (fosteropenscience.eu)

Open-science practices include:

- Publishing your work in open-access journals (so that anyone can read your work)

- Sharing your methods (e.g. publishing them on protocols.io)

- Sharing your data

- Sharing your code (e.g. github.com)

We talked about how daunting it can be to release protocols or code but how beneficial it can be to both the wider scientific community and yourself.

PREreview

The last issue raised was about learning how to critically appraise work. One way to get practice at reviewing work in a safe and supported environment is by creating a PREreview journal club. This is a journal club that discusses and reviews preprints (manuscripts released by authors prior to peer-review).

PREreview (Post, Read, and Engage with preprint reviews) is a website hosting reviews of preprints created in journal clubs (https://www.authorea.com/inst/14743-prereview).

“Reviewing preprints benefits the authors, as they receive early feedback on their manuscript. Early-career researchers benefit from the opportunity to develop their critical thinking and peer-review skills. And the whole scientific community benefits from access to scientists’ discussions about the latest discoveries.” (https://elifesciences.org/labs/57d6b284/prereview-a-new-resource-for-the-collaborative-review-of-preprints )

We have started a PREreview channel on the GOS-ICH slack for those who are interested in improving their critical appraisal skills.

Hopefully through improving teamwork and being more open, we can help foster a supportive, collaborative environment at the Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health. If you’re at GOSICH and want to join this endeavour – sign up to the SLACK workspace (find out how by emailing Sophie at sophie.adler.13@ucl.ac.uk) and get involved!

Written by Daniyal Jafree a MB/PhD student, supervised by Dr David Long and Professor Peter Scambler in the Developmental Biology and Cancer programme, studying how lymphatics in the kidney develop. Lymphatics are specialised tubes which clear debris, excess fluid and immune cells from organs. They have important roles in kidney disease, but how they appear and grow in the kidney in the first place has been a complete mystery.

Written by Daniyal Jafree a MB/PhD student, supervised by Dr David Long and Professor Peter Scambler in the Developmental Biology and Cancer programme, studying how lymphatics in the kidney develop. Lymphatics are specialised tubes which clear debris, excess fluid and immune cells from organs. They have important roles in kidney disease, but how they appear and grow in the kidney in the first place has been a complete mystery. Thanks to tremendous luck, an extremely supportive team and a mouth-wateringly fancy microscopy facility at PGCRL, it took us 9 weeks to test our strange idea of where lymphatic cells in the kidney are coming from. What we found was really surprising, and challenges what we thought we know about how lymphatics develop. The next trick will be to test whether we can exploit this to target lymphatics in kidney diseases; an ongoing aim in David’s laboratory.

Thanks to tremendous luck, an extremely supportive team and a mouth-wateringly fancy microscopy facility at PGCRL, it took us 9 weeks to test our strange idea of where lymphatic cells in the kidney are coming from. What we found was really surprising, and challenges what we thought we know about how lymphatics develop. The next trick will be to test whether we can exploit this to target lymphatics in kidney diseases; an ongoing aim in David’s laboratory. Close

Close