Peace Education and Action for Impact: Towards a model for intergenerational, youth-led, and cross-cultural peacebuilding

By Blog Editor, on 11 July 2022

Peace Education and Action for Impact: Towards a model for intergenerational, youth-led, and cross-cultural peacebuilding

World BEYOND War partners with the Rotary Action Group for Peace to pilot a large-scale peacebuilding programme

The need for intergenerational, youth-led, and cross-cultural peacebuilding

Sustainable peace rests on our ability to collaborate effectively across generations and cultures.

First, there is no viable approach to sustainable peace that does not include the input of all generations. Despite general agreement in the peacebuilding field that partnership work among different generations of people is important, intergenerational strategies and partnerships are not an integral part of many peacebuilding activities. This is not surprising, perhaps, given that there are many factors that mitigate against collaboration, in general, and intergenerational collaboration, in particular. Take, for example, education. Many schools and universities still prioritise individual pursuits, which favour competition and undermine possibilities for collaboration. Similarly, typical peacebuilding practices rely on a top-down approach, which prioritises the transfer of knowledge instead of collaborative knowledge production or exchange. This in turn has implications for intergenerational practices, because peacebuilding efforts are too often done ‘on’, ‘for’, or ‘about’ local people or communities rather than ‘with’ or ‘by’ them (see, Gittins, 2019).

Second, while all generations are needed to advance the prospects of peaceful sustainable development, a case can be made to direct more attention and effort toward younger generations and youth-led efforts. At a time when there are more young people on the planet than ever before, it is hard to overstate the central role youth (can and do) play in working towards a better world. The good news is that interest in the role of youth in peacebuilding is rising globally, as demonstrated by the global Youth, Peace, and Security Agenda, new international policy frameworks, and national action plans, as well as a steady increase in programming and scholarly work (see, Gittins, 2020, Berents & Prelis, 2022). The bad news is that young people remain under-represented in peacebuilding policy, practice, and research.

Third, cross-cultural collaboration is important, because we live in an increasingly interconnected and interdependent world. Therefore, the ability to connect across cultures is more important than ever. This presents an opportunity for the peacebuilding field, given that cross-cultural work has been found to contribute to the deconstruction of negative stereotypes (Hofstede, 2001), conflict resolution (Huntingdon, 1993), and the cultivation of holistic relationships (Brantmeier & Brantmeier, 2020). Many scholars – from Lederach to Austesserre, with precursors in the work of Curle and Galtung – point to the value of cross-cultural engagement.

In summary, sustainable peace is dependent on our ability to work intergenerationally and cross-culturally, and to create opportunities for youth-led efforts. The importance of these three approaches has been recognised in both policy and academic debates. There is, however, a lack of understanding about what youth-led, intergenerational/cross-cultural peacebuilding looks like in practice – and specifically what it looks like on a large scale, in the digital age, during COVID.

Peace Education and Action for Impact (PEAI)

These are some of the factors that led to the development of Peace Education and Action for Impact (PEAI) – a unique programme designed to connect and support young peacebuilders (18-30) across the globe. Its goal is to create a new model of 21st century peacebuilding — one that updates our notions and practices of what it means to do youth-led, intergenerational, and cross-cultural peacebuilding. Its purpose is to contribute to personal and social change through education and action.

Underpinning the work are the following processes and practises:

- Education and action. PEAI is guided by a dual focus on education and action, in a field where there is a need to close the gap between the study of peace as a topic and the practice of peacebuilding as a practice (see, Gittins, 2019).

- A focus on pro-peace and anti-war efforts. PEAI takes a broad approach to peace – one that includes, but takes on more than, the absence of war. It is based on the recognition that peace cannot co-exist with war, and therefore peace requires both negative and positive peace (see, World BEYOND War).

- A holistic approach. PEAI provides a challenge to common formulations of peace education which rely on rational forms of learning at the expense of embodied, emotional, and experiential approaches (see, Cremin et al., 2018).

- Youth-led action. Frequently, peace work is done ‘on’ or ‘about’ youth not ‘by’ or ‘with’ them (see, Gittins et., 2021). PEAI provides a way of changing this.

- Intergenerational work. PEAI brings intergenerational collectives together to engage in collaborative praxis. This can help to address the persistent mistrust in peace work between youth and adults (see, Simpson, 2018, Altiok & Grizelj, 2019).

- Cross-cultural learning. Countries with diverse social, political, economic, and environmental contexts (including diverse peace and conflict trajectories) can learn a great deal from each other. PEAI enables this learning to take place.

- Rethinking and transforming power dynamics. PEAI pays close attention to how processes of ‘power over’, ‘power within’, ‘power to’, and ‘power with’ (see, VeneKlasen & Miller, 2007) play out in peacebuilding endeavours.

- The use of digital technology. PEAI provides access to an interactive platform that helps to facilitate online connections and supports learning, sharing, and co-creation processes within and between different generations and cultures.

The programme is organised around what Gittins (2021) expresses as the ‘knowing, being, and doing of peacebuilding’. It seeks to balance intellectual rigour with relational engagement and practice-based experience. The programme takes a two-pronged approach to change-making – peace education and peace action – and is delivered in a consolidated, high-impact, format over 14 weeks, with six-weeks of peace education, 8-weeks of peace action, and a developmental focus throughout.

Implementation of the PEAI pilot

In 2021, World BEYOND War teamed up with the Rotary Action Group for Peace to launch the inaugural PEAI programme. This is the first time that youth and communities in 12 countries across four continents (Cameroon, Canada, Colombia, Kenya, Nigeria, Russia, Serbia, South Sudan, Turkey, Ukraine, USA, and Venezuela) have been brought together, in one sustained initiative, to engage in a developmental process of intergenerational and cross-cultural peacebuilding.

PEAI was guided by a co-leadership model, which resulted in a programme designed, implemented, and evaluated through a series of global collaborations. These included:

- The Rotary Action Group for Peace was invited by World BEYOND War to be their strategic partner on this initiative. This was done to enhance collaboration between Rotary, other stakeholders, and WBW; facilitate power-sharing; and leverage the expertise, resources, and networks of both entities.

- A Global Team (GT), which included people from World BEYOND War and the Rotary Action Group for Peace. It was their role to contribute towards thought leadership, programme stewardship, and accountability. The GT met every week, over the course of a year, to put the pilot together.

- Locally-embedded organisations/groups in 12 countries. Each ‘Country Project Team’ (CPT), comprised of 2 coordinators, 2 mentors, and 10 youth (18-30). Each CPT met regularly from September through December 2021.

- A ‘Research Team’, which included people from the University of Cambridge, Columbia University, Young Peacebuilders, and World BEYOND War. This team led the research pilot. This included monitoring and evaluation processes to identify and communicate the significance of the work for different audiences.

Activities and impacts generated from the PEAI pilot

While a detailed presentation of the peacebuilding activities and impacts from the pilot cannot be included here for reasons of space, the following gives a glimpse of the significance of this work, for different stakeholders. These include the following:

1) Impact for young people and adults in 12 countries

PEAI directly benefited approximately 120 young people and 40 adults working with them, in 12 different countries. Participants reported a range of benefits including:

- Increased knowledge and skills related to peacebuilding and sustainability.

- The development of leadership competencies helpful for enhancing personal and professional engagement with self, others, and the world.

- Increased understanding of the role of young people in peacebuilding.

- A greater appreciation of war and the institution of war as a barrier to achieving sustainable peace and development.

- Experience with intergenerational and cross-cultural learning spaces and practices, both in-person and online.

- Increased organising and activism skills particularly in relation to carrying out and communicating youth-led, adult-supported, and community-engaged projects.

- The development and maintenance of networks and relationships.

Research found that:

- 74% of participants in the programme believe that the PEAI experience contributed to their development as a peacebuilder.

- 91% said that they now have the capability to influence positive change.

- 91% feel confident about engaging in intergenerational peacebuilding work.

- 89% consider themselves experienced in cross-cultural peacebuilding efforts

2) Impact for organisations and communities in 12 countries

PEAI equipped, connected, mentored, and supported participants to carry out more than 15 peace projects in 12 different countries. These projects are at the heart of what ‘good peace work’ is all about, “thinking our ways into new forms of action and acting our way into new forms of thinking” (Bing, 1989: 49).

3) Impact for the peace education and peacebuilding community

The conception of the PEAI programme was to bring intergenerational collectives together from across the globe, and to engage them in collaborative learning and action toward peace and sustainability. The development of the PEAI programme and model, along with findings from the pilot project, have been shared in dialogue with members from the peace education and peacebuilding community via various online and in-person presentations. This included an end-of-project event/celebration, where young people shared, in their words, their PEAI experience and the impact of their peace projects. This work will also be communicated through two journal articles, currently in process, to show how the PEAI programme, and its model, have potential for influencing new thinking and practices.

What next?

The 2021 pilot offers a real-world example of what is possible in terms of youth-led, intergenerational/cross-cultural peacebuilding on a large scale. This pilot is not seen as an end-point per se, but rather as a new beginning – a strong, evidence-based, foundation to build on and an opportunity to (re)imagine possible future directions.

Since the beginning of the year, World BEYOND War has been working diligently with the Rotary Action Group for Peace, and others, to explore potential future developments – including a multi-year strategy which seeks to take up the difficult challenge of going to scale without losing touch with the needs on the ground. Regardless of the strategy adopted – intergenerational, youth-led, and cross-cultural collaboration will be the heart of this work.

Author Biography:

Phill Gittins, PhD, is the Education Director for World BEYOND War. He is also a Rotary Peace Fellow, KAICIID Fellow, and Positive Peace Activator for the Institute for Economics and Peace. He has over 20 year’s leadership, programming, and analysis experience in the areas of peace & conflict, education & training, youth & community development, and counselling & psychotherapy. Phill can be reached at: phill@worldbeyondwar.org. Find out more about the Peace Education and Action for Impact programme here: at https://worldbeyondwar.org/action-for-impact/

Give Peace Education a chance: A Citizenship-based educational approach

By Blog Editor, on 14 June 2022

By PGCE Citizenship Student Teachers 2021-2022: Aroosa Azam, Samed Karadal, Shanti Kandola-Wade, Jess Duggan, Fatima Ahmed & Suhasini Bostone.

What is ‘Peace Education’?

We, unfortunately, live in a world where too often humans resort to violence and war as a primary tool to resolve disputes and responding to challenges – Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the ongoing Ethiopian civil war (Tigray War), or rising tensions and standoffs between China and the US over Taiwan and the South China Sea. Amongst this backdrop, what can teachers do to support students to understand the world around them, in a safe, and supported way? The answer is perhaps a simple one – ‘Peace Education’. But what is Peace Education?

Before we look at Peace Education, a good starting point is unpacking what ‘peace’ is. We could use the dictionary definition of ‘peace’, but instead we adopt Johan Galtung’s definition. Galtung asserts that peace is like a coin – it has two sides: ‘negative’ and ‘positive’. ‘Negative peace’ refers to the absence of violence and is negative because something undesirable (e.g., violence or war) has ended, but can always restart, for example in the Korean War, where tensions between North Korea and South Korea still exist but are kept at bay by the Korean Armistice Agreement signed in 1953. ‘Positive peace’ refers to the attitudes, institutions and structures within society that allow for peaceful societies to be born and flourish, such as charitable causes like Amnesty International.

Positive Peace is then the end goal of Peace Education, because by adopting a positive peace mindset, as individuals we can improve and clear our headspace, improve our coping and critical thinking skills, and improve our overall mental and physical health. We can then use our internal positive peace to be creative in solving problems within our daily lives in our societies and in the world. Inner positive peace will enable us to communicate with one another productively and positively, and ultimately, this will lead to the cultivation of the structures and changes in society that will allow for positive peace to flourish in society.

The question for Peace Education is then, how do we achieve ‘Positive’ Peace? It intends to allow students to explore their relationships and their belonging at the personal (inner), peer, community, and societal level. Through Peace Education, students are equipped with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values necessary to preventing conflict, resolving them peacefully and creating the social conditions that enable peace.

Education for Peace is underpinned by 4.7 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations General Assembly, 2015). This is supported by Fundamental British Values (‘FBV’), such as mutual respect and tolerance for others, which is why it can be integrated through a curricular approach. With this in mind, citizenship education is one of the most effective ways of delivering peace education in secondary schools. The National Curriculum for Citizenship does not reference peace education explicitly, but it explores related concepts (Department for Education, 2013). In Key Stage 3, the capacity for students to foster a culture of conflict resolution extends across topics, such as, human rights and responsibilities, the global community and the role of voluntary organisations in society. Throughout Key Stage 4, students extend their knowledge through the exploration of diverse identities, the UK’s involvement in international organisations and international law.

UNICEF describes peace education as a “tool to deliver conflict-sensitive education” (2016, p.vii). GCSE Citizenship lessons that focus on balancing the right to life, the overseas work of Oxfam, the role of the United Nations Security Council and its members in armed conflict, for example, enable the development of critical thinking skills, problem-solving and the foundational knowledge that is vital for this purpose. In doing so, we have the opportunity to fulfil the aims of citizenship education and create changemaking citizens with an orientation for justice.

Peace education provides an opportunity to respond to the evolving diversity of British society and addresses calls to decolonise the curriculum. It provides enriched learning by fostering an appreciation for different approaches to academic study – engaging with non-western ideology, female, and minority narratives. Importantly, peace education redresses reductive Eurocentric perspectives on conflicts which can, at times, neglect the lived realities of the global population that have been impacted by colonial legacies. Peace education presents an ideal opportunity to champion this more holistic approach to education by focusing upon a range of case studies, such as Ukraine, Palestine, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Yemen, Iran, and Myanmar. Pupils are offered a variety of historical discourses, which respond to the diversity of some classrooms and wider society.

The commitment to peace education is not a purely academic pursuit to be embedded into the curriculum, but incorporated into wider school practices and ethos. The report ‘Peace at the heart’ published by Quakers in Britain (2022) stresses the idea of the school as a community whereby a peaceful environment can be cultivated to challenge othering, nurture students’ as advocates for themselves and crucially enjoy learning. The report critiques the tendency of schools to implement strict behaviour policies which violate children’s rights outlined in the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child, which include education and dignity. Instead, the report suggests pursuing a ‘restorative’ approach of communication and problem-solving to resolve conflict, rather than focusing upon sanctioning individuals. In addition, students can also be supported to resolve their own conflict through peer mediation schemes, and as a result develop social and emotional skills including communication, empathy and awareness of wellbeing needs. Whilst the practices of ‘restorative’ approaches to behaviour and peer mediation are not new, the pursual of peace education as a whole-school approach and ethos enables schools to cultivate a safe learning environment whereby students are supported and giving the tools to engender peace, and constructive, cooperative, and healthy interpersonal relationships.

Teaching peace education may appear to be a simple, harmonious venture that instantly sparks consensus within the citizenship classroom. However, where there is peace, there has been conflict, which may be reflected in student discussion. Rather than cowering at the thought of tension in the classroom, the teacher can seize the opportunity to create cohesion between students through peace education. As the Crick report (1998) said:

“Education should not attempt to shelter our nation’s children from even the harsher controversies of adult life, but prepare them to deal with such controversies knowledgeably, sensibly, tolerantly and morally” (pp.56).

First and foremost, the teacher should anticipate the likelihood for controversy between their students. This can be optimised by considering the student demographic. For example, during one author’s experience at a secondary school, the Russian invasion of Ukraine was of imminent concern as the conflict broiled. Hence, this prompted a whole-school awareness campaign, delivered during tutor time. In advance of fostering any conflict-related discussion during tutor time, the teacher had become acutely aware of the demographic of their tutor group; including both a Ukrainian and a Russian child. Throughout delivery of Ukraine-related content and any subsequent discussion the teacher ensured to set firm ground rules and expectations of positive language and behaviour. What followed was good-natured and compassionate deliberation of a tragic ongoing war.

Peace education is not just the domain of the humanities and social sciences. Knowledge and understanding of peace can be promoted through all curriculum subjects. Below we list some examples of ways this can be done:

RE: Explore responses and campaigns for peace from religious and non-religious groups and communities. (Editors Note: This blog will explore RE as a subject to teach peace education and RE/Citizenship peace education links in future issues).

Art: Exploration and discussion around art as a form of protest against war. For example the painting ‘Guernica’ by Pablo Picasso, which famously depicts the horrors of the Spanish Civil War.

Sciences (Chemisty/Biology/Physics): The teaching of atomic structures and chemical bombs in the context of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

English: Exploration of war poems in the GCSE ‘power and conflict’ theme.

Geography: Human geography, exploring migration patterns and borders as a result of conflict. E.g., Ukraine conflict/ Poland.

History: War and peace treaties e.g., Paris Peace Accords post-war Vietnam

Music: Similarly, art is a medium that can be incorporated as a hook to instantly engage students in the lesson, and to explore protest songs. Linked is a curated playlist by the PGCE citizenship cohort of peace education themed songs.

Over time and as citizenship specialists, we are becoming more knowledgeable about peace education. Our role in citizenship education enables us to instil in learners the values, attitudes, behaviours and knowledge to become responsible global citizens. In doing so, we hope to upskill students in their quest for creative solutions to any type of conflict, whether it is internal or external. As teachers of peace education within the realm of citizenship, we plan to educate our students about their rights as citizens of a nation and members of a school, to establish a communal and global understanding of peace. Peace education provides a unique opportunity to do all of this and more, through adoption in the curriculum with citizenship specialists. The citizenship community acknowledges that our role is to show students that there is hope, to equip them with the necessary skills to make an impact and to demonstrate that through agency, they can be empowered to build a better tomorrow (Svennevig, 2021).

References

Crick, B. (1998) Education for citizenship and the teaching of democracy in schools: Final report of the Advisory Group on Citizenship. London: QCA.

Department for Education (2013). National curriculum in England: citizenship programmes of study.

Galtung, J. (1969). ‘Violence, Peace, and Peace Research’, Journal of Peace Research, 6 (3), pp 167-191. https://www.jstor.org/stable/422690

Quakers in Britain (2022). Peace at the heart: A relational approach to education in British schools.

https://www.quaker.org.uk/documents/peace-at-the-heart

United Nations General Assembly (2015). Sustainable Development Goals.

UNICEF (2016). UNICEF Programme Report 2012 – 2016: Peacebuilding, education and advocacy in conflict-affected contexts programme, p.vii.

https://www.unicef.org/media/96556/file/UNICEF-PBEA-Final-Report.pdf

Svennevig, H. (2021). ‘Our Responsibilities for Peace Education for the Next Generation’, Teaching Citizenship, 54, pp. 51-54. https://issuu.com/associationforcitizenshipteaching/docs/teachingcitizenship_issue54_autumn_21_digital

UCL Peace Education Launch Symposium July 7th 2022 5-7pm @IOE

By Blog Editor, on 1 June 2022

Join key advocates for peace education from around UCL on July 7th 5-7pm as they make the case for peace education in personal, educational, and societal terms:

Join key advocates for peace education from around UCL as they make the case for peace education in personal, educational and societal terms

About this event

Background

Peace education has never been more important than it is today. Despite its long history, peace education has never found a place in the curriculums that it deserves. There is a great richness of activity taking place in peace education, but it has often existed on the margins of mainstream practice. Now, in the face of war in Europe, educators are demanding resources, knowledge and strategies to develop students’ understandings of this conflict, and human conflict more generally.

How can we give peace education a higher profile?

Peace is a key aspect of the Sustainable Development Goals and should be given as much priority as sustainability. We need to raise its profile to reveal its relevance for social justice. We need to do this by establishing its crucial role in the health of society, from critical thinking, media literacy, to environmental responsibility and democratic agency. Peace is part of the pedagogy of learning and now that there is an urgency to explore this area with a rich evidence base – we as educators need to consider how we promote it to all corners of curricula.

Background reading

To provide further context, you may want to check out:

- The recent Quakers in Britain report “Peace at the heart“

- The Education for Peace and Non-Violence section of “Target 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence in Schools in England“, a recent report prepared for the Our Shared World coalition.

Who are the event organisers?

This symposium on peace education is part of the activities of the Peace Education Special Interest Group at IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society. This relatively new group aims to bring peace educators across educational spheres together. You can read more about the group on the UCL Peace Education blog.

The co-Chairs of this particular event are Hans Svennevig (IOE, Subject Lead: Citizenship PGCE / Teaching Citizenship journal) and Alexis Stones (IOE, Subject Lead: Religious Education PGCE).

Event aims

Please join us as we launch the public activities of this group with a symposium that aims to make the case for peace education in personal, educational and societal terms, and explore ways this might be achieved.

Time will be dedicated to establish ways forward to galvanise expertise and interest, among individuals and networks, to act as a collective and embed peace education in practical and policy terms across all educational fields.

Event format

This is a hybrid event. The initial keynotes of this event will be possible to stream live online. You will also be able to post questions and comments. However, during the networking and planning section, the in-person and online attendees will be split into separate groups for interactive discussions. You will need to select whether you will attend virtually / online, or in person, during checkout.

Who is this event for?

This event is aimed at peace education practitioners, education professionals, teachers, academics and policy makers. Keynote speakers will present ideas in relation to the fields of sustainability education, citizenship education, Religious Education, history education, young people and activism.

You will be able to connect to organisations and individuals about how to support your own education for peace, whether in school, university, further education, museums, or public education.

Event timings

17:00 -17.45: Keynote speakers

- Welcome by co-Chairs Hans Svennevig and Alexis Stones (IOE)

- Introduction session from Maria Hantzopolous and Monisha Bajaj: authors of Educating for Peace and Human Rights: An Introduction

- Giles Duley (Legacy of War Foundation)

- Ellis Brooks (Peace Education coordinator, Quakers)

- Doug Bourn (IOE)

18:00 – 19:00: Sharing and planning for next stage working groups

Peace at the Heart: making the case for putting good relationships at the centre of education

By Blog Editor, on 3 May 2022

Isabel Cartwright from QPSW Education

“It fills me with hope…I’m imagining a future where the cycle of harmful behaviour policies is broken…definitely speaks to me as a teacher.”

These were the words of one trainee teacher about our new report Peace at the heart: A relational approach to education in British schools. In a way this feedback meant as much to me as the many hours of research, discussion and evidence-gathering that went into the report.

Peace at the Heart presents Peace Education as a comprehensive approach to teaching and learning that puts good relationships – peace –at its heart. Written by David Gee, Isabel Cartwright and Ellis Brooks for Quakers in Britain, a faith group committed to equality and peace, the report presents the evidence for a relational approach and shines a light on schools already putting peace at their heart. It makes five recommendations for the governments of England, Scotland and Wales to support Peace Education in line with their international commitments.

“The years that young people spend in education shape their whole lives. Their sense of self, relationships, and life chances…begin to mature in this period.” (Peace at the Heart, 2022 report, pp 3) If you’re a student, teacher, policy maker, or anyone interested in schools as healthy communities, then we hope it speaks to you too.

Why do Quakers care?

Quakers have been concerned about education since their origins in the 17th Century. The belief that the Divine Light is within everyone, leads Quakers to believe that children, like adults, are able to have a direct relationship with God that requires no intermediary. Children are valued in their own right, rather than as grown-ups in the making. Motivated by the belief that education can nurture ‘that of God’ in everyone, Quakers believed from the outset that it should be available to all, girls as well as boys, a radical view at the time. In secular terms, this could be expressed as valuing everyone’s humanity.

This belief in ‘that of God’ in everyone also led Quakers to take a clear stand for peace. The Quaker peace testimony (it’s called a “testimony” because it is how Quakers witness to the world about their beliefs) leads Quakers to try to live out their commitment to peace in their daily lives and in their work.

Today, Quakers’ faith commitment to truth, peace, simplicity and equality still leads them to work towards schools where people matter, where they thrive through relationships and where the beauty of the whole person is affirmed.

“The purpose of education is the pursuit of learning, knowledge and questioning in the service of realising our full human potential in an ever-changing world… The outcome of this approach will be a fair, diverse, just and good society.” (Quaker Values in Education Group).

So Quakers aren’t so much educating about their religion as they are educating for peace.

Making the Case for Peace Education

Peace is understood as more than the absence of war, or ‘negative’ peace as founding father of Peace Studies, Johan Galtung defines it. ‘Positive peace’ is what’s sought, the attitudes, institutions and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies, including the flourishing of Human Rights.

“I feel peace education is about teaching children to discover that they have the power to change things they see are wrong and developing the imagination to find alternative responses to conflict. This is not an objective for a course called ‘Peace’ on the timetable. It must permeate all our teaching. For we cannot teach one thing and act another.” Quaker Faith & Practice 23.85

In our Peace Education work, we were inspired by schools embracing peace at different levels, individual wellbeing (peace with myself), healthy peer relations (peace between us), an inclusive school community (peace among us), and the integrity of society and the earth (peace in the world). Increasingly schools were investing in peace and adopting a whole school approach, supported by partner organisations such as Peacemakers, RJ Working and Transforming Conflict. Movements such as Peaceful Schools and the growing network of Peace Schools supported by the Welsh Centre for International Affairs were showing the commitment of schools to build a culture of peace.

We were struck by the way teachers responded to the ‘peacekeeping’, ‘peacemaking’ and ‘peacebuiding’ lense presented by Cremin and Bevington (2017). These schools were building positive peace without the need for the ‘zero tolerance’ or ‘ready to learn’ type approaches gaining so much attention.

In 2019 our partners in Brussels, the Quaker Council for European Affairs, made a policy case at the European level in Peace education: Making the case. We decided we should make the same case in the British context.

A relational approach

In collating many example of peace education practice, we found that the common commitment seemed to be to the integrity of relationships.

The report explores the different layers of peace and shows their interconnection. Take individual wellbeing for example. As the report argues, the investment in mental health support for individual pupils has had little impact on the prevalence of anxiety and depression. To tackle these effectively, schools need also need to focus on developing healthy peer relations and creating an inclusive school community.

“A genuinely peaceful school becomes somewhere students and staff feel valued and believe they can flourish – it becomes somewhere they want to be. Indeed, research shows that students who enjoy school a lot tend to point to strong friendships, a sense of belonging, and the confidence that teachers believe in them.” (Peace at the Heart, 2022 report, pp 5)

This relational approach brings many evidenced benefits. These include the fuller development of young people, a more effective learning environment in school, and emerging citizens who are more conscientiously involved in their society. “Young mediators have become community workers and peacebuilders, former gang members have become youth coaches, teachers have witnessed their relationships with students transformed.” (Peace at the Heart, 2022 report, pp 7)

A focus on relationships is sometimes criticised for being at odds with clear expectations of behaviour, and systems that support calm environments conducive to learning. But a relational approach using restorative practice has demanding expectations. As the report argues, disciplinarian type approaches often actually deny young people the chance to take responsibility for their actions, or contribute to the life of the school community.

The report shows how the increase in these approaches in England has been accompanied by a sharp rise in school exclusions, compounding social inequality.

“…those eligible for free school meals are four times as likely to suffer exclusion, those with special educational needs twice as likely, and Gypsy and Roma students four times as likely. Exclusions are also used disproportionately to punish students of colour”. (Peace at the Heart, 2022 report, pp 24)

The report also shows how some schools, particularly in Scotland and in Wales, take an alternative approach, and how this has dramatically reduced exclusions.

Recommendations

Peace at the Heart shows that even with limited investment, there is substantial evidence of the difference peace education can make. The report documents the strong United Nations mandate for peace education, but the lack of statutory support in Britain. Many schools are not within reach of a peace education training provider, and without bursaries would struggle to pay for necessary support. In addition to calling for a clearer mandate and investment in peace education, the report recommends more guidance in terms of relationships with external organisations.

External voices can enrich education and can build empathy and insight, but there are blind spots where some inherently political questions are depoliticised while others seem to be subject to a chilling effect. Schools have a longstanding duty to impartiality, but Quakers and our partners have watched government endorsed engagement of weapons manufacturers and the armed forces in school life with no acknowledgement that this raises political issues. Whereas questions of antiracism, LGBT inclusion or peacebuilding in Palestine & Israel are avoided for fear of controversy. The report therefore makes the following five recommendations:

- The governments of England, Scotland and Wales explicitly recognise a duty to educate for peace.

- Teacher training institutions supported to embed peace education as a dedicated study stream.

- Funding established to enhance school communities and develop existing training providers while seeding new ones.

- Research and evaluation into how schools can embed, sustain and evaluate peace education particularly restorative practices.

- External contact. Governments issue guidance on screening external contacts according to the educational value of their interventions and schools’ legal duty to safeguard students from exploitation.

‘Peace at the heart: A relational approach to education in British schools’ launched on 11 May 2022, find out more and view the peace education videos at: www.quaker.org.uk/ /peace-education-case

References:

Cremin, H. and Bevington, T. (2017) Positive Peace in Schools: Tackling Conflict and Creating a Culture of Peace in the Classroom, London: Routledge.

Gee, D., Cartwright, I., Brooks, E. (2022) Peace at the heart: A relational approach to education in British schools (2022): https://www.quaker.org.uk/documents/peace-at-the-heart

Quaker Faith & Practice (2013) fifth edition, The book of Christian discipline of the Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain.

Zwart, D. (2019) Peace education: Making the case https://www.qcea.org/peace/peace-education-report/

Isabel (Izzy) Cartwright is the Peace Education Programme Manager at Quakers in Britain. Her passion for peace and justice comes from volunteering in play schemes in Northern Ireland, living on-board the Japanese Peace Boat, informal and community education and work in schools in East London. Find out more about Quaker Peace Education at www.quaker.org.uk/peace-education

Peace education for a new world by Professor Douglas Bourn

By Blog editor, on 19 April 2022

The war in Ukraine has raised the issue of peace education. How do teachers respond to questions from children about the conflict? What resources are available? How can teachers be better equipped to address these challenging questions.

It needs to be noted that peace education is not a new area within education. It has a long and strong tradition within English education systems as in many other countries around the world. Whilst the area has often been subject to political attacks by governments, many teachers have brought in themes of peace, conflict resolution, mediation and understanding of causes of war into their classrooms. Some of this has come through religious education, others through citizenship and also through history.

This blog contribution suggests there is a need however to bring in peace education themes more directly into learning opportunities that are addressing global and sustainability issues. For example, the term global citizenship is a popular buzz phrase at present but surely to be an effective global citizen means being a peaceful one.

The UN Sustainable Development Goals have become popular themes in schools for making connections between local and global issues. There has rightly been a focus on climate change and sustainability but peace should only be seen as equally relevant, some of the threats to war in the future may well relate to environmental issues. That is why Sustainable Development Goal 16 is so important: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

Within these Sustainable Development Goals, which all countries have signed up too, there is Target 4.7 which states:

By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development

The promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence is included here but it is a concept that has had, up until now, less discussion than say human rights on sustainability. What is needed is in taking forward the relevance of Target 4.7, is to ensure that peace education is recognised as equally important as the other themes.

This may well happen because of the war in Ukraine but it needs to go beyond making passing references to conflict and war and to look at ways in which peace education can be more than learning about war and conflict to identifying from a pedagogical perspective what learning through peace can actually mean.

One attempt to address this in England has been the Our Shared World initiative which is a coalition of over 200 civil society organisations and higher education institutions. This initiative has as its goal the embedding of Target 4.7 of the SDGs into the English school curriculum. An Evidence and Research report for this network, to be launched on April 25th, states that if a concern for social justice, independent and critical thinking and community participation is to be part of education, then peace education can be a key lens through which to perceive a more just and sustainable world.

The challenge is how to ensure that teachers and teacher educators have the knowledge, skills and expertise to put these themes into practice. It is much more than just having a session on peace education when training teachers. There is a need for teachers to be reminded as to why they came into education, having a moral purpose and an approach that encourages learners to develop a values base based on social justice, respect for human rights and sense of co-operation.

Author:

Douglas Bourn, Professor of Development Education at UCL-IOE, author of Theory and Practice of Development Education (2015) Understanding Global Skills for 21st Century Professions (2018) Education for Social Change (2022) and editor of The Bloomsbury Handbook for Global Education and Learning (2020). He is also chair of the Academic Network of Global Education and Learning (ANGEL) Advisory Board.

“Be thou more sheltering, God. Pay more attention.” – response to Tony Kushner for hope in heartless times

By Blog editor, on 28 March 2022

Ongoing and deadly attacks on the people in Ukrainian cities, towns, villages, homes, hospitals, schools and a theatre, amidst hopes for ‘humanitarian corridors’, all affirm the scale and dehumanisation of war. Marina Ovsyannikova’s protests on live news leaving her long-term prospects still uncertain, and the tens of thousands of detained protesters in Russia, demonstrate that words and actions are indeed a privilege.

Suffering persists for the dispossessed, the ‘survivors’, and victims of countless global conflicts. Plights of refugees remain a constant reality across the world. Resilience, solidarity, social action, charity, aid, local and global support, kindness and care abound, and yet old and young flee war for the second and third time, children grow up war-torn and babies are born in war.

Words feel hopeless compared to the urgent needs of individuals and communities who are invaded or suffer under the threat of invasion. Inspired by Lisa Birman’s “A Prayer” (1996), this response to Tony Kushner’s “Aids Prayer” (1994) is an attempt to use words to speak to the heart in heartless times. In the face of the AIDS pandemic, Kushner petitions God for justice and a cure. While God is used here as an address, this God is also a goddess, a god, G-d, gods, a principle, a truth, an aspiration, a hope.

“Be thou more sheltering, God. Pay more attention.”

– response to Tony Kushner’s “Aids Prayer” in heartless times

“Dearly Beloved, Let us pray.

[Dear] God: A cure would be nice. Rid those infected by this insatiable unappeasable murderer of its lethal presence.”

A cure for war, we ask

For war, for invasion, for indiscriminate and discriminate violence.

When ceasefire occurs, for reconciliation

When peace occurs, for listening to flourish.

When homes are built, stories told, for trauma healed not handed on

For story converted to allegory: tales of inner resolvable conflict

Outer peace to yield inner peace.

May anger alert us to injustice (not force)

May fear and pride make peace

May what divides us, do so peacefully

May the exhausted and embattled not need bravery.

Your neglect leaves us besieged, God

We shake our fists at you and your corridors of humans

Wars known and unknown

Suffering heard and unheard

In the Great Court, who will the Jury find guilty?

We ask you to turn your face to us

“At present we are homeless, or imagine ourselves to be…

Be thou more sheltering, God. Pay more attention.”

Further Reading:

“Aids Prayer” for the Episcopalian National Day of Prayer for AIDS (Tony Kushner, 1994)

“A Prayer” (in “Some Things: poems and translations”, Lisa Birman 1998, Dristill Press)

What can peace education do on the eve of war?

By Blog Editor, on 22 February 2022

At the time of first writing, the headlines were saying invasion is “imminent” in Ukraine. Now Russian forces have occupied Donetsk and Luhasnk, with the threat of more intense violence still looming. That shouldn’t mean educators fall silent.

Young people do not exist in a bunker from reality – they hear the news and others talking about it. Many will know that something is up with Ukraine, Putin and Russia, even if no-one has talked to them about it. Silence about war is scary.

When violence escalated in Gaza in 2021, downloads of our education resources about Palestine & Israel increased dramatically, suggesting teachers were responding to the news in their classrooms.

Peace education can sometimes (and powerfully) focus only on the interpersonal level and leave war aside, perhaps fearing it is “too political”. This feeling may be still greater among teachers in England following the government’s new guidance on political impartiality. But a peace educator doesn’t campaign against war in the classroom. They help students build the combination of knowledge, empathy and critical reflection needed to be ethical, active citizens. So what would a peace education lesson about the prospect of war in Ukraine look like? What questions might we ask in the classroom?

Who is involved in the conflict?

Neville Chamberlain, UK Prime Minister at that time, said of the 1938 crisis in Czechoslovakia, it was a “quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing”.

Today, despite the internet and increased global travel, many of us could say the same of Ukraine. How much do most British students – or indeed adults – know about Ukraine and Ukrainians? Or Russians for that matter, outside the stereotypes of James Bond movies. How do the Russian and Ukrainian students feel in the classroom as the news unfolds?

There are good human geography lessons to explore these diverse cultures. There are also compelling real stories of the people experiencing conflict, including journalists risking it all to tell the truth, Russian conscripts or Ukrainian conscientious objectors like Ruslan Kotsaba. What would we do in their shoes? Students could explore religious identity in both societies, including the 2019 split of the Eastern Orthodox Church and faith communities working for peace. Who are the Crimean Tartars? Ethnic Russians?

These are real people. Building empathy is one component of peace education. Chamberlain was in effect saying that the British people at the time, still living with the memory of World War I, wouldn’t care to go to war for so remote a people, but the effect can work the other way. A people ‘about whom we know nothing’, or not enough, is one whom we can unconsciously dehumanise, reducing them to statistics on the news.

Why could war break out?

To understand the present conflict, peace education can lead us to study history, and there’s lots to understand about Ukraine. As the Soviet Union came to an end, many Russians and Ukrainians were involved in nonviolent mass-movements including 300,000 Ukrainians who made a human chain for independence in 1990. There is more on the timeline to understand: Ukraine giving up its nuclear weapons and joining the Non-Proliferation Treaty; NATO’s expansion and Russians’ sense of betrayal’, Ukrainian movements from the orange revolution to the Maidan Revolutions. Perhaps it would be useful to look back further, to Britain’s Crimean War; to the USSR’s experience of World War 2 or ‘The Great Patriotic War’; to the Cold War and life in the USSR; to the Chernobyl disaster; or to the Holodmor, in which millions of Ukrainians starved under Stalin’s rule. What in this history contains the roots of the present conflict, and what needs to be addressed to make peace?

There are also contemporary Citizenship questions: what role do the arms trade or fossil fuels play? What is the UK’s role? What international law applies to war? What are the rights of the people involved: children, refugees, casualties, prisoners? From peace studies, learners can also gain insights into ideas such as structural violence, conflict escalation, cycles of violence.

During the onset of war, leaders’ rhetoric can be reductive, decrying any diplomacy as ‘appeasement’. We also know propaganda and “psy-ops” are an omnipresent part of modern warfare. If the first casualty in war is the truth, then education becomes doubly important so that citizens can see past the slogans, and exercise critical thinking. Perhaps that would make a good English Language or media studies lesson, but students need to be capable of evaluating the narratives purporting to explain why war is happening.

Is war bad?

Yes. War is bad, and it’s OK for teachers to say so.

Even those who say that war is sometimes necessary would generally concede that the experience is grim for everyone, unbearable for many. There’s no shortage of human experience teaching us about the suffering war causes.

For soldiers and their families, for civilians caught in the middle, for those forced to flee, for those left behind. This is not controversial, and our experience shows students can and want to grapple with the moral questions it raises.

But society is guilty of mixed messages on war. With media and culture rife with stories of redemptive violence and triumphs of arms, it is understandable if young people are drawn to the glamour and numb to the dangers. The regular presence of arms companies and military activity in education may also undermine a school’s duty to provide balanced views. Education needs to address the reality.

There are many perspectives to explore. RE teachers can draw on the different ideas on war and peace across different faith traditions. Literature can immerse us imaginatively in war; one of Britain’s most celebrated poems, The Charge of the Light Brigade, depicts heroic folly in war. History can explore the causes and effects of war, zooming in on the lived experience as well as the politics. The lives of Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale might feel relevant too. Given four of the powers negotiating over Ukraine’s fate are nuclear armed states, the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons is also worth understanding, perhaps with resources from CND Peace Education or the Nuclear Education Trust.

Photo: Quakers in Britain

The facts of war must be handled sensitively in the classroom – students shouldn’t be traumatised. Teachers should also strive to be impartial about the political agendas surrounding war. But if democratic citizens are to engage meaningfully with a question like “should this war be fought?” it should be done with an understanding of the human consequences.

How do we make peace?

Peaceworkers time and again have to work against short-termism. The dilemma on the eve of war is too often reduced to “will you fight or do nothing?” What this ignores is the peacebuilding that can and should be done long before violence, addressing the needs of the parties involved and binding their interests. Think of the politicians desperately flying around on diplomatic missions, of the weapons flowing from East and West; could this energy and wealth have been more wisely spent in the preceding years?

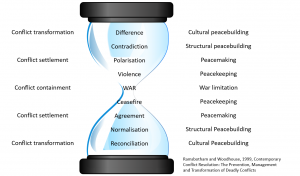

A helpful model of war from Peace Studies is the hour-glass. At its widest it provides space for conflict transformation, building peace and justice. As it narrows, options become limited to mere peacekeeping, or failing that, striving to contain the excesses of war.

The hour-glass also opens up gradually after we pass the narrow aperture of war, allowing for gradual normalisation and perhaps even reconciliation; planning for this post-war is important too. Lessons from the Rwanda genocide or the Coventry blitz show the power of peace even in the recollection of horror.

This model can help students understand many conflicts past and present, including Ukraine. It suggests the skills we could learn for each level: exchange and co-operation to build relationships when we see difference; mediation to get parties talking when they become polarized, which many school children practise every day; restorative justice when harm has taken place. There are myriad peacebuilding practices, and indeed careers for young-people so led. As Ivan Hutnik, a Quaker experienced in international conciliation and conflict transformation, puts it, ‘for real peace, the solutions need to be multi-layered and nuanced.’

Peace education is itself part of peacebuilding. Activities like the World Peace Game can help students role-play international challenges. The skills and processes required by the leaders responding to conflict in Ukraine can be learned, and students can practise them in the classroom, their everyday lives and careers.

The hour-glass is a reminder that education shouldn’t wait until that narrowing of options; the peace education ought to long before the eve of war.

Start somewhere

Peace education should start long before the eve of war and it’s no less relevant when violence breaks out.

If you had to run a 15 minute presentation the day war breaks out, what would you say? Perhaps I’d attempt a truncated version of this blog. First, war is bad and scary; talk to staff about your feelings. Second, the story behind the war is complicated, so ask questions and learn. Remember real people are involved, whether friend or enemy; we can hold all frightened people in our thoughts or prayers. And finally, there are ways to work for peace. That’s about all you could say.

But what else could you teach given time? Peace education isn’t extra-curricular. Throughout RE, English, History, Citizenship, PSHE, Social Studies, RE, Geography, not to mention Further Education or Higher Education, inspection frameworks, learning outcomes proliferate including conflict resolution, understanding the UK’s relations with the wider world, the Cold War, understanding different cultures, human rights, evaluating different narratives, reflecting on one’s own beliefs, religion peace and war. Across curricula a combination of knowledge, emotional engagement and ethical reflection can combine to help students own their own civic responsibility. Teachers and educators shouldn’t be afraid to go there.

War today is the failure of yesterday. The shadow of war continues to throw up some of the worst experiences and dilemmas humans can face. Questions that seem unanswerable, stakes incalculable. That is why they can’t be avoided – teachers and educators have to start somewhere. If we are to find better answers than war, we need peace education.

Author Biography:

Ellis Brooks is the Peace Education coordinator at Quakers in Britain. His passion for peace and justice comes from volunteering in Palestine, Afghanistan and in his home country of Britain, campaigning on issues including the arms trade, nuclear weapons and violent immigration systems. Having worked as a teacher, Ellis has experience of the both the pain and the peacebuilding that exist in schools. Find out more at www.quaker.org.uk/peace-education

Our responsibilities for peace education for the next generation

By Blog Editor, on 1 February 2022

“I am going to do something different… I am going to ask you the reader for your time”.

Introduction:

In this blog post I share a piece that is featured in the ACT 54th issue of Teaching Citizenship Journal which itself is a write-up and slight modification of a conference keynote that I presented on 21st May as part of the ‘The Possibilities of Peace Education: Evidence and Opportunities’ QCEA online conference from Brussels, Belgium. I consider how we all need to think differently about how we frame peace for the next generation, some of the resources and techniques to use to develop skills and knowledge in this area. I consider how peace education can be used as part of citizenship education and how this can be developed over institutions at any level especially within UCL I discuss how this is being included in teacher education at IOE including within PGCE Citizenship currently. Most of all I ask a moment of your time.

Our Responsibilities for Peace Education for the Next Generation

I am going to do something a little different at the start of this article. I am going to ask you the reader for you time. This is a bold move, as we all are short of time and we want to read and get through things as quickly as possible. I ask that if you are reading this, and have no time, come back to it later (as a free to access blog, that’s easy to do). I do not ask this lightly – you may indeed read the whole piece and feel that I have missed something out – I am sure I have. But I ask this of you so that you can explore the elements of peace education that I tried to present to the conference delegates when this was originally presented. I thank you for allowing me the indulgence of your time.

As you cannot immediately ask me any questions (you are welcome to write to me) I want to pose some questions to you. I would like you to spend some time – maybe a minute or so to consider and reflect on each question before moving on to the next. The power of silence in our busy and chaotic lives brings with it a form of inner reflection, inner peace.

In peace education, how can we teach young people about:

Drone warfare?

The impact of COVID on structural inequalities?

The consequences on warfare due to the climate emergency?

Increased militarisation and securitisation in nation states in Asia, Europe and the Americas?

Potential conflict in places like Palestine/Israel and Ukraine/Russia?

Continued turmoil in nations such as Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethopia, Sudan and Cameroon?

The continuing global arms race, including the increased proliferation of nuclear weapons?

Countering violent extremism?

Social injustices?

Violent knife/gun crime in the streets?

Divisive messaging leading to increases in ‘othering’?

The large displacement of people around the world and their treatment?

Thank you reader for thinking through these questions and giving them some real pause and reflection. When considering these very hard hitting questions, you may have started to think about all the problems and complications in the world, the challenges we all face in our various nations related to authoritarian governments, the creeping securitisation of the state, the limiting of freedoms and so on. To me when I wrote those questions and thought about my role at UCL, Senate House, kept coming to mind. Senate House was the inspiration for the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell’s 1984. It speaks to me of the doom and gloom of what might happen, and often creepingly seems to be happening, or the consequence in doing nothing.

When thinking about those questions that I presented before and thinking about our responsibilities we may feel that the urgency compels us to talk and consider what will happen if we don’t do something, anything. It may compel us to consider the very big problems, which in turn may make us and others to feel very small and hopeless and focus on the worrying thoughts, and that these are all really too overwhelming to do much about. That we are in fact hopeless to make a difference.

The Norwegian sociologist and founder of peace and conflict studies Johan Galtung says “the view that one cannot meaningfully work for both absence of personal violence and for social justice can also be seen as essentially pessimistic as some sort of intellectual and moral capitulationism” (1969: 186). The next generation has enough doom to experience by watching the news, yes they need to be informed but they are often more informed than we, through their connections to social media – and an education many of us never had.

I pose that our responsibility to the next generation is to provide hope in a world of hopelessness to provide the skills that they can use to make an impact, to consider and understand the world around them, to be accepting and encouraging, kind and compassionate, to build transformative relationships with the big questions, to consider notions of peace education in all subjects at all education levels and through all themes, and to be empowered through their agency to build a better tomorrow with small steps. To build empathy and to lead the way. As you develop teaching materials for big questions like those that I have posed think about how to reframe the discussions. Think about your responsibilities, the glaring obvious are the problems we face – let’s talk more about the solutions and provide an opportunity for hope, for learning about what can and often is being done.

It is our role to reframe how we engage with young people and students, and how we talk to them, the expectations we have of them as citizens of our communities, the skills they possess to help us to be better. This is how we can start working toward notions of as Galtung said the two types of peace, negative (absence of personal violence) and positive peace (absence of structural violence). It is our responsibility to do so.

In my own work at IOE, UCL’s Faculty of Education and Society I have the privilege and opportunity to educate the next generation of citizenship teachers with strong citizenship subject knowledge and citizenship pedagogic skills. As well as the various curriculum requirements of the PGCE, and principles of social justice, human rights and democracy I’ve worked to intersect peace education into the curriculum to ensure that these new teachers are appropriately trained to teach such elements effectively. As we know Citizenship education is often contested in the UK and England as much as it is throughout other nations and so at the IOE we enable citizenship teachers to have a full breadth of the notion of citizenship education in England as first conceptualised by Crick and added to over time by various changes in the national curriculum, as well as the rich work of individuals and groups such as Ajegbo, Starkey, Jerome, Kerr, Osler, Hantzopoulous, Bajaj, Hess, ACT, Young Citizens, the Politics Project, Parliament Education Service the list goes on and on.

As Professor Hugh Starkey notes citizenship education is about ‘learning to live together’ and this is a key element of peace education. Citizenship education in the English context is about our rights as democratic active citizens and it is about exploring these rights in the classroom, peace education and positive peace is clearly an essential component of these. We work to develop student teachers knowledge of the curriculum, but also the skills that they will come to develop in their own students – to participate and lead active citizenship, transformative peace education, sustainability education, human rights, and political democratic organising. At UCL through our new Peace Education Special Interest Group and this blog we are also working with colleagues to increase peace education more widely among students and staff wherever they may be found.

I ask you to look back at those questions that we reflected upon earlier, again. How can you as an educator of any other subject specialism reframe the answers? To empower and enrich our students no matter their age? How can you give actionable hope to the next generation?

Let’s think about how we pose the answers, how we share and frame the discussion, how we can pose these with positive local, national and international actions that have led to change, that have led to peaceful resistance and campaigning for human rights and peace perspectives, that have led to the skills and knowledge that we can bring about to resolve these complex themes. I ask you to ponder how can we bridge negative and positive peace, inner, interpersonal and wider world peace?

I suggest that we can start to do this through empathy. Through celebrating and recognising difference. Through educational resources such as Fly Kites not Drones inspired by Afghan Peace Volunteers, or resources from CND Peace Education, or QPSWs Razor Wire and Olive Branches or celebrating the success of the ban on nuclear weapons (a huge success). We can consider these notions of peace when using resources from ACT on the deliberative classroom or building resilience project or the range of ideas and materials in Teaching Citizenship Journal for example on Protest Songs or Critical Media Literacy. We can build peace when we consider the role of Race, LGBTQ+ rights and decolonising the curriculum through schools and university reading lists to incorporate wider voices. We can use resources from the Peace Education Network such as Teach Peace Primary or the soon to come Teach Peace Secondary. Resources from The Black Curriculum, Diversity Role Models, CitizensUK, Protection Approaches, The Refugee Council, the Peoples History Museum, The Migration Museum. We can utilise the voices of film makers like Leon Oldstrong and films such as https://www.fairtrademovie.co.uk/ or social influencers that tear down the walls of othering to explore what unites us, food, travel near and far. We can use the voices of students themselves like social action opportunities developed for young people from FirstGive or Young Citizens or pupil power initiatives set up by Aliyah York or the work of the Hamilton Academy #OurVoiceYourChoice students or for Higher Education via the National Union of Students or work like the Student Action for Refugees Project. The list of possibilities to improve the lives of our young people and students, and give them the skills to live and make hopeful change in a complicated world are endless, indeed they are essential for everyone’s long term enjoyment of peace and prosperity. That is particularly why when working with my colleague Alexis Stones we decided it would be useful to set up a Special Interest Group in Peace Education to promote the work at every level of UCL.

While we are considering the resources to use to inspire the next generation, let’s think about our own everyday language and how we can work to change that, to be hopeful and inspiring, recognising the hard work needed but enabling us all to work towards tangible small, medium and long term impacts. Let’s think about resources and skills that we can use promote inclusive opportunities. Let’s talk about how movements build and grow over time and how small steps lead to positive action. Let’s empower young people to know that small things can and do make a difference. That they REALLY do make a difference. Just look at the Friday climate strikes and the attention we now have on that issue. Let’s empower agency, that is our responsibility to the next generation. We owe it to them to give them the skills to make change, and then helping them to make the change.

As I draw to the end of this blog post I thank you the reader for that time you gave me at the start, and I hope that what I have written about has given you a few ideas, has made you feel a bit more hopeful about how things are, and have reminded you that you can and ARE galvanising young people and students to lead us forward. You might feel that I am being overly positive, I too am human and see how things are all around, but with the privilege that I clearly have I need to do all I can to work towards hope.

I just want to remind you of what all of this is about, it’s about our universal human rights wherever or whoever we are. It’s about our rights to peace. And let’s not forget the enormous hope and hard work that went into creating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights after war and how countless young and old people have benefitted throughout the years through that work. We must continue our responsibilities to the next generation to enable them to continue that work, to strengthen it. As QCEA’s 2018 report indicates we need to move away from just good intentions we need to continue to raise awareness and build secure peace education learning opportunities that everyone can access regardless of background, identity or citizenship status… as we are all citizens, and so we need to make sure that these places of peace education are conflict-sensitive.

There is work to do – but let’s be proud and hopeful of that work to inspire others and enable the next generation to lead. Because none of us are free, and safe from incivility or structural violence until we all are, that we as individuals only have dignity when we all have dignity.

Other resources I recommend reading – that inspired this piece:

-https://freshedpodcast.com/hantzopoulos-bajaj/ Maria Hantzopoulos & Monisha Bajaj; Education for Peace and Human Rights

-Amit Puni’s Podcast on Citizenship education: https://citizenshippodcast.podbean.com/

-Educating for Peace and Human Rights; Hantzopoulos & Bajaj: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/educating-for-peace-and-human-rights-9781350129719/

-Children’s Rights Education in Diverse Classrooms: Pedagogy, Principles and Practice; Starkey & Jerome: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/childrens-rights-education-in-diverse-classrooms-9781350062825/

-The Prevent Duty in Education, Impact, Enactment and Implications; Buscher & Jerome: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007%2F978-3-030-45559-0

-Lessons from Lockdown; Breslin: http://www.breslinpublicpolicy.com/transform-education-dot-org-dot-uk/

Blog purposes

By Blog Editor, on 1 February 2022

The Peace Education Special Interest Group Blog Purpose:

The purpose of the peace education special interest group blog is to bring together ideas around peace education and how these can be developed at UCL and in education more widely. As the SIG progresses we will be able to start putting forward suggestions for developing peace education at UCL. We are very pleased to be able to invite and include different academics and peace educators within this blog and later in the year at the start of our formal celebratory launch we will develop these conversations through networking opportunities both online and in person to bring together a range of practitioners.

In our first post – I (Hans) write about how we can think about peace education for the next generation.

Peace Education Special Interest Group Launch

By Blog Editor, on 10 January 2022

Peace Education Special Interest Group at UCL Blog Launch

Welcome to our readers interested and inspired, motivated and hopeful to learn, share, develop, and grow in the subject of Peace Education. The Peace Education Special Interest Group has been set up by Hans Svennevig and Alexis Stones subject leaders of PGCEs (Initial Teacher Education) in Citizenship education and Religious Education respectively. We have been able to form this group with support from Professor Nicola Walshe Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment Head of Department whom we thank.

This blog will be the mouthpiece of activities and announcements, reflections and considerations related to the special interest group including events and opportunities for collaboration, to hear from Peace Education activists, students, teachers and academics. We invite you to get in touch with us if you would like to contribute to the special interest group or have an idea or activity that you would like to share to further peace education at every level of UCL. We will update this blog frequently – with the next edition to examine some of the themes around peace education and how it can be incorporated in teaching at every level. Later in the summer we hope to have an event to bring peace educators together and consider a longer term strategy and vision for the special interest group.

We are looking forward to working with the UCL community and see Peace Education as a core component of the overall long term vision and strategy of UCL.

Close

Close