Source: Flickr.com – México PFP by Jesús Villaseca Pérez. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

This week, a great deal of media outlets reported that Mexico was the second deadliest conflict zone in the world, just below Syria’s civil war, and ahead of war-torn countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan and Yemen.

The news reports drew on a newly-launched edition of the Armed Conflict Survey (ACD) published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), a London-based think tank. The survey analyses different dimensions of on-going armed conflicts around the world, including figures on fatalities, refugees and internally displaced persons.

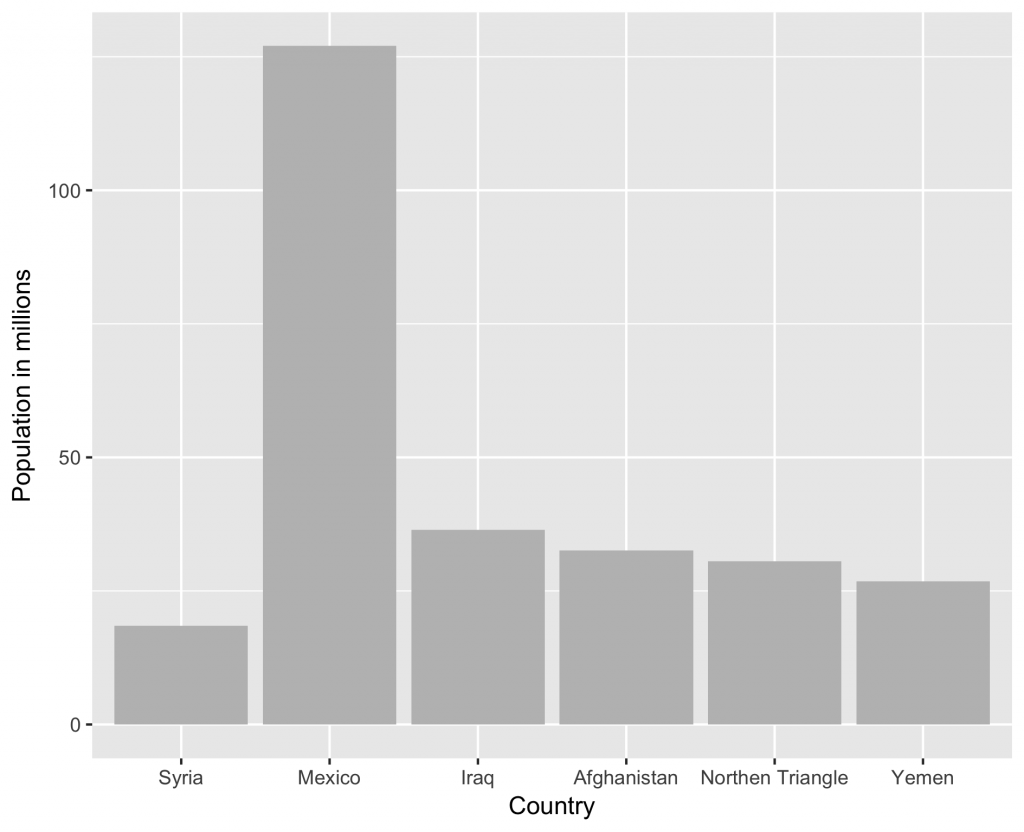

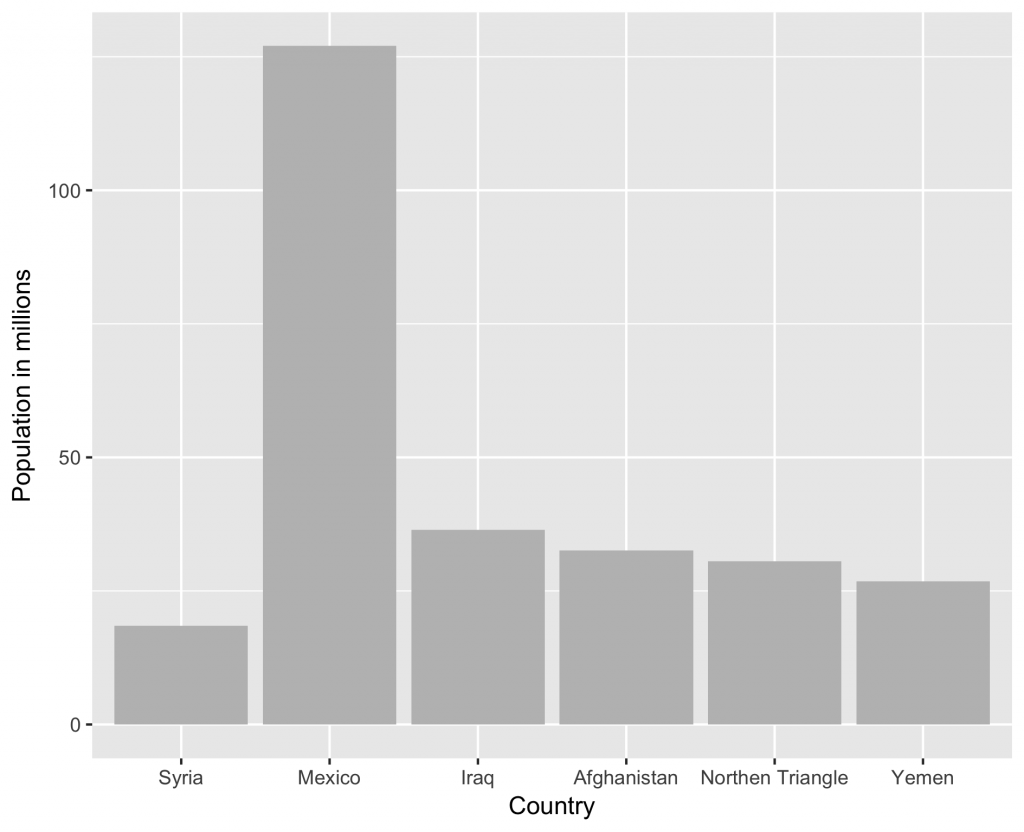

In a press release issued to promote the launch of the ACD, IISS makes the claim that the second deadliest conflict in the world is Mexico’s struggle against organised crime, which they claim caused 23,000 deaths in 2016. The most lethal conflict, Syria’s civil war, caused 50,000 deaths, while Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen follow Mexico. The only other countries in Latin America considered by the survey were El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala—the so-called “Northern Triangle”.

Conflict related fatalities as reported by the Armed Conflict Survey 2017.

That Mexico, the 11th largest economy in the world by purchasing power parity, could be placed in the same list as countries ravaged by international conflicts involving heavy artillery caused a media frenzy, including a retweet by President Donald Trump, as well as a rebuke from the Mexican government.

The survey conclusions are deeply misleading for two main reasons.

1. It compares countries with very different population sizes

When mortality or homicides are compared cross-nationally it is necessary to adjust figures by population size. For example, a hypothetical country A had 100 homicides for a population of 1 million people, while country B had 500 homicides for a population of 10 million people. In absolute terms, country B had 5 times more homicides than country A. However, once population sizes are taken into account, country A had 10 homicides per 100,000 people, while country B had 5 per 100,000 people. Thus country A can be thought of as twice as lethal than country B.

Bringing this hypothetical scenario to reality, consider the example put forth by Alejandro Hope, a security analyst in an interview with a Mexican TV network:

United States has a more than twice the number of homicides than Honduras, yet no one in their right mind would argue that the United States is twice as dangerous as Honduras.

For this reason, cross-national comparisons of homicide figures are almost always done in rates for 100,000 people, as this comparison of homicides in Latin America, or the international homicide observatory set up by the Igarapé Institute. Once the different population sizes are taken into account (USA: 321 million; Honduras: 8 million), it is evident that the United States’ roughly 12,000 homicides represent a far smaller rate per 100,000 people (3.9) than Honduras’s 6,000 homicides (84.6 per 100,000 people).

Antonio Sampaio, a security researcher at IISS, said to Reuters that the ACD did not use rates for the cross-national comparisons because many of the countries in the study do not have good quality population statistics.

However, this obstacle is hardly enough justification when comparing countries with populations so dissimilar in size as Mexico, Syria and Iraq. Mexico’s population (127 million) is one order of magnitude bigger than all of the countries in ACD’s list of the top 5 deadliest conflicts. To put that into perspective, Mexico’s population is larger than the population of Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Yemen combined (114.2 million). It is true that precise estimates of a country’s population are not always available, and that accurate statistics in fragile, conflict-torn countries are hard to come by, but the difference between the populations of the countries in the survey is too large to be ignored.

Population estimates from Google Search.

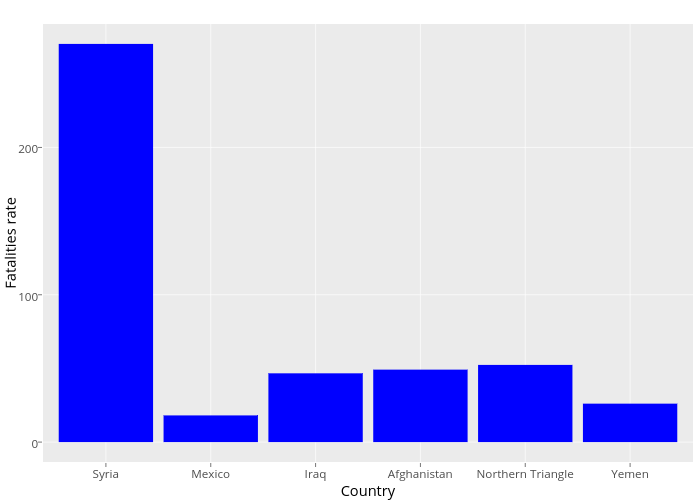

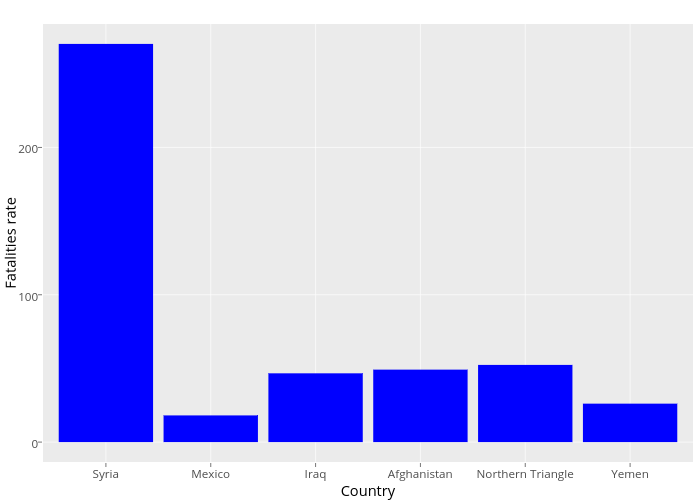

Thus, even if relying on (approximate) population estimates from the earliest available year, it is necessary to adjust the fatalities listed by the ACD by population. The plot below compares the rates per 100,000 people in the countries listed by IISS as the top 5 deadliest conflict zones, plus the countries in the Northern Triangle, using fatalities reported by the survey and population estimates from Google Search. Taking rates into account, México is not even close to being the “world’s second deadliest conflict zone,” as its rate is less than half of that of Iraq, Afghanistan, and the countries in the Northern Triangle.

Estimated rates of conflict-related fatalities per 100,000 people as reported by the armed Conflict Survey 2017, using population data found on Google Search, provided by the World Bank.

2. Not all homicides in Mexico can be attributed to organised crime violence

The other questionable assumption in the survey is that all of the 23,000 fatalities in Mexico are attributable to organised crime violence. The press release issued by IISS does not specify the data source used to estimate that figure, though an IISS blog post mentions that these correspond to intentional homicides. In response to an email, Sampaio confirmed that the figure is the total number of victims of intentional homicide as reported by Mexico’s National System of Public Security, which is based on data compiled by state prosecutors.

Precise estimates are not available, though Tom Long, Lecturer of International Relations at the University of Reading, stated to The Guardian that “probably half of Mexican homicides are not related to drug trafficking”. For example, if we took only those homicide reports involving firearms as being more likely to be related to organised crime violence, they amount to 60% of the total (around 13,000 homicide reports), a much lower figure as that cited by the survey.

It is true that Mexico has a problem of organised crime violence. And it is also true that homicides in Mexico increased in 2016, and it is likely that a sizable proportion of these homicides were related to organised crime.

However, assuming that all homicide fatalities in Mexico are related to organised crime is fallacious, even if a more precise measurement is not available. Furthermore, the qualitative nature of homicidal violence in Mexico is vastly different from the calamitous atrocities happening in Syria, Irak, Afghanistan, or Yemen.

There is much to study about Mexico’s organised crime phenomenon, but equating it to civil wars, and muddying public perception, does more harm than good.

Close

Close