Guest post from Ian Caswell, UCL Press Journals Manager.

When discussing peer review, generally, I find it helpful to remind myself of some of the values as to perhaps why researchers publish in scholarly journals. In essence, it usually comes down to these 4 headings.

- Knowledge and discovery

- Evaluation and validation

- Credit

- Access to research

Within this environment, peer review is arguably the fundamental gold standard aspect of scholarly and academic publishing and is, at least in its most fundamental use of it, the facilitator for publishers to sell journals and its content.

So then, what is the role for peer review precisely, and what does it serve to accomplish?

An easy question to answer, right? In the book Editorial peer review: It’s strengths and weaknesses, the author writes the role of what peer review serves is, as ‘the goal of the process is to ensure that the valid article is accepted, the messy article cleaned up, and the invalid article rejected,’ thereby ensuring that the article made available to the reader is quality controlled.

In another book titled Peer review: A critical inquiry, the author here writes that the process of peer review also benefits the author, as they are later certified by the process if published proceeding peer review: “Careers are often made or destroyed by the process.”

In scholarly publishing, peer review acts to validate and assess work and is the current system used to assess the quality of a manuscript before it is published. Other experts in the relevant field assesses the research or article for things like fact, validity, and significance, that aid the assessors (i.e. Editors) to determine whether the manuscript should be published in the journal or not. I think it is pertinent to remember here that journals do play a vital role in the scientific and scholarly process, by refining research through peer review and disseminating it to appropriate communities by publication, and it is this role of review by peers that has been a part of scholarly communication since the appearance of the first journal in the 17th Century (see the brilliant book by Professor Aileen Fyfe et al, A History of Scientific Journals: Publishing at the Royal Society, 1665-2015.)

Challenges in peer-review

There has been a lot of discussion around the challenges peer review present, stemming from bias and prejudices towards authors, fraudulent behaviour, non-expertise reviews, and so on. In the article Peer review in a changing world: An international study measuring the attitudes of researchers by Mulligan et al in 2012, notes that:

“Although alternative forms of peer review have evolved to tackle issues of bias, it is less clear what effect, if any, they will have upon fraud. High‐profile cases of fraud and plagiarism have brought the debate about the efficacy of peer review to a wider audience, attracting greater public attention. Such incidences include [certain individuals], tipped to be a Nobel Prize winner, who published a series of fraudulent papers that were withdrawn from Nature, Science, Physical Review, and Applied Physics Letters.”

Journals typically tackle these types of concerns by anonymising authors and reviewers from each other to ‘enable a fairer and just review system’. In this article Mulligan et al surveyed around 40,000 published researchers that were randomly selected from the Web of Science (then known as the Thomson Reuters ISI list) and concluded that the majority of respondents were happy with the current system, but noted the system is imperfect and more can be done to ensure a higher level of efficacy and efficiency.

Now, being led by open science principles, it is largely seen that being more open and transparent with research publication and assessment can we increase scholarly rigor, accountability and trust.

What is open peer-review?

There is a growing evidence base of the challenges and flaws in the current anonymised peer review system (albeit, mainly within the biomedical and clinical sciences), and major publishers and journals are already testing open peer review processes (or have already implemented a practice of it already).

In April 2017, a systematic review of what open peer review is was published online in F1000Research (itself an innovative model of open peer review). It concluded: “Open peer review has neither a standardized definition, nor an agreed schema of its features and implementations. The literature reflects this, with a myriad of overlapping and often contradictory definitions.”

What this review very accurately depicts, is that there are a number of definitions of open peer review that can be collated together into themes and it purports there are 7 open traits to what open peer review concerns itself with, and that open peer review can take either a single aspect, or a multitude or mix of any of these traits, to operate as an open peer review model. Briefly, these are:

- Open identities, where authors and reviewers are aware of each other’s identity.

- Open reports, where the review reports are published alongside the relevant article

- Open participation, where the wider community are able to contribute to the review process

- Open interaction, where direct reciprocal discussion between author(s) and reviewers, and between the reviewers themselves, is allowed and encouraged

- Open pre-review manuscripts, essentially, a pre-print server, where manuscripts are made immediately available (e.g., BiorXiv) in advance of any formal peer review procedures

- Open final-version commenting, where the review or commenting on the final “version of record” is published

- Open platforms (or “decoupled review”), where review is facilitated by a different organizational entity than the venue of publication

What is UCL Press doing?

At UCL Press, we launched our very own open peer review and open science journal called UCL Open Environment: a fully non-commercial, Open Science journal, publishing high impact, multi-disciplinary research, on real world environmental issues, with the overall aim of benefitting humanity. The journal is for any researcher or professional at knowledge-based universities, institutions, and organisations (including Non-Government Organisations, Think Tanks, Inter-Government Organisations, and the United Nations) and submissions are invited from those at all career stages, including early career researchers, mid-career professionals, and senior scholars. There are also no barriers to the Open Peer Review Process (whereby the identity of the reviewer and the report are made publicly visibly at all times); engagement from all will advance the greatest leaps and discoveries.

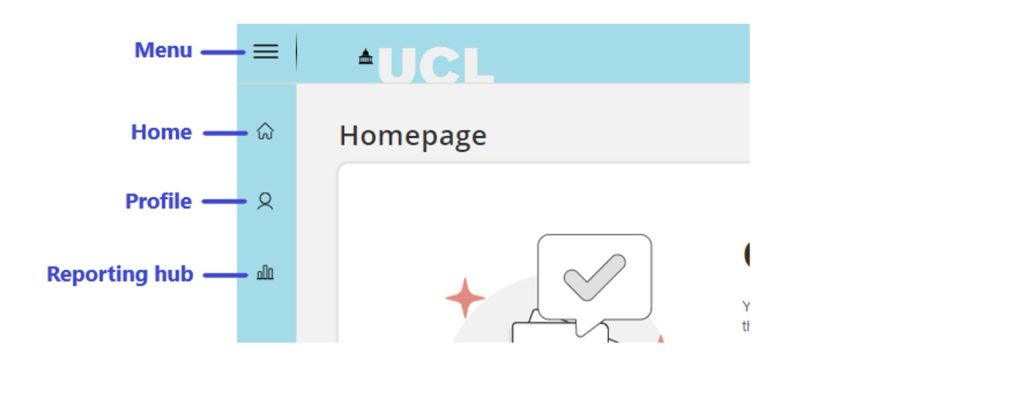

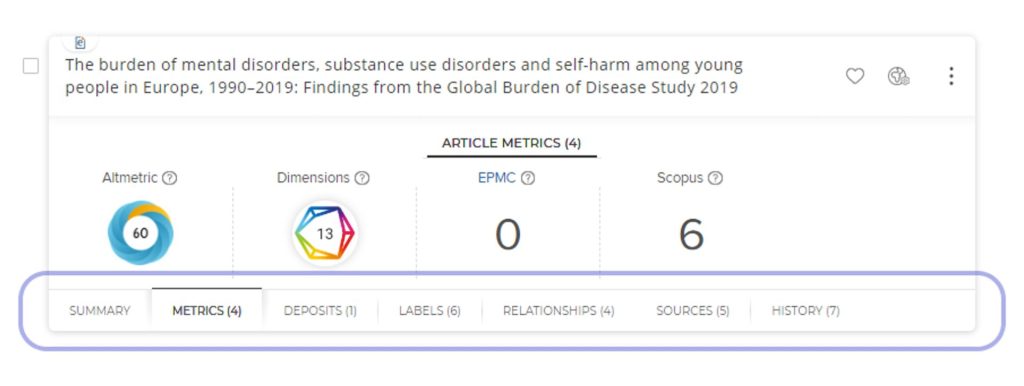

Reviewers are firstly asked to sign in to the system using their ORCID account and when they submit their review report, the report is posted up online in the preprint server alongside the article, under the CC-BY licence and assigned a unique DOI. You can find out more information about this at https://ucl-about.scienceopen.com/for-reviewers/peer-review-process.

Reviewers can therefore attain credit of their report and readers are able to follow the process openly online. We hope this will also aid the development for others (especially earlier career researchers and students) with examples on how a review is written and how an article is revised accordingly, aiming to improve the way we should engage critically and beneficially with research.

Readers of this blog can see for themselves how the journal works (you can see here the list of the latest submissions and open peer reviews, as well as here for publications accepted after peer review). It is my hope that readers will be encouraged to provide more open peer reviews or open comments, adding to the corpus of open debate around research, and consider contributing to UCL Open Environment, as we believe that by removing barriers and innovatively working openly and together will we accelerate finding solutions to the world’s most significant challenges.

Close

Close