Specimen of the Week 385: UCL skulls

By ucwehlc, on 12 July 2019

This blog was written by Lily Garnett, volunteer at the UCL Pathology Museum

UCL.16.009 and UCL.16.018 are skulls. Like any human face, although they have the same features, they look different. They have both been processed for medical teaching, with cuts and hooks to reveal the inner workings of the cranium.

In terms of provenance, the history of these two individuals remains a mystery. The UCL prefix to their number indicates that they were found within the collection and their history prior to this is unknown. Before accurate plastic models became available in the 1990s, real human bones were used for teaching.

But where do you get a skeleton from?

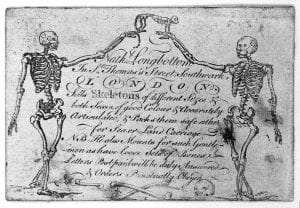

There are some elaborate 18th and 19th century trade cards for ‘skeleton suppliers’, such as Nathaniel Longbottom of St Thomas’s Street Southwark. Although this indicates that you could go and buy a human skeleton from a shop, there is no indication as to the original source of the skeletons. Of course they may have acquired them in completely legitimate circumstance, but the likelihood of body donation at this time is unlikely.

Mr Longbottom’s card reads

Nath. Longbottom in St. Thomas’s Street, Southwark, London sells skeletons of different sizes & both sexes, of good colour & accurately articulated; & packs them safe either for sea or land carriage

L0015028 Trade-card of Nathaniel Longbottom, supplier of skeletons

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0

Anatomy Act

In the 19th century people made every attempt to prevent their bodies to be dissected for medical teaching. The prevailing Christian belief that bodies must remain intact for Resurrection made the idea of dissection repellent for the majority. The demand for human remains increased grave robbing, and in instances such as Burke and Hare, led to people being murdered just to supply medical institutions. To prevent the increasing fear of the bodies of love ones being stolen, in 1832 the Anatomy Act was passed. This act allowed doctors to take any corpse that was left unclaimed at the city morgue or hospital. The change in law put an end to grave robbing in the UK, but supply did not reach the medical institutional demands. So British doctors looked to the colonies and found a supplier in India.

To take one example, Adam, Rouilly is one of the longest established manufacturers and suppliers of anatomical models supplying UK universities. The company started in 1918 when Monsieur Guy Rouilly and Mr Adam took over E. Rouilly and Sons which had until this point manufactured and supplied architectural fittings. The name was changed to Adam, Rouilly and the products supplied also changed when Rouilly found a real skull while visiting a customer. On taking this chance find to Middlesex Hospital Medical School he was asked if he could provide more and realised there was a gap in the market as the demand for skeletal remains to be used for teaching outreached the supply. Thus their trade in importing skeletons began.

From the 1930’s Adam, Rouilly purchased skeletal human remains from the firm of Reknas Ltd in Calcutta, which remained the main export until 1985. This means that the vast majority of skeletons that were purchased by medical students as teaching tools from 1930, especially if they are from Adam, Rouilly have travelled here from India, most probably regions around Calcutta. C.6. in the UCL collection is an example of a medically mounted temporal bone by Adam, Rouilly, and is therefore most probably the remains of an individual from India.

Black Market

In 1985 the Indian government outlawed the export of human remains, but this has no stopped a black market in remains. This came following the arrest of a bone trader who was exporting 1,500 child skeletons. The skeletons of children were much sought after and could command higher prices as they illustrated osteological development. It sparked rumours that reached Indian newspapers and claimed children were being kidnapped and killed for their bones. In the absence of any large competing suppliers from other countries, India’s export ban shut down the international trade of human skeletons, to a certain degree. It forced the transition to plastic teaching models.

Although it is now not considered the norm for medical students to require a real skeleton in order to support their study, the demand for such human remains is still present and there is an active black market. Common law in the UK states that there is no ownership in a corpse, and many online UK sellers explain that the human remains that they are selling are antique medical specimens for private collections not public display. It’s probably that remains such as these have travelled all the way from India.

References:

- http://www.adam-rouilly.co.uk/content/history.aspx

- https://www.wired.com/2007/11/ff-bones/?currentPage=all

- https://strangeremains.com/2015/04/17/i-want-to-frame-these-18th-century-fliers-for-skeleton-suppliers/

4 Responses to “Specimen of the Week 385: UCL skulls”

- 1

-

2

Fossil Friday Roundup: July 19, 2019 wrote on 28 March 2020:

[…] Specimen of the Week 384: UCL skulls (UCL Blogs) […]

-

3

Fossil Friday Roundup: July 19, 2019 – The Official PLOS Blog wrote on 12 May 2020:

[…] Specimen of the Week 384: UCL skulls (UCL Blogs) […]

-

4

Can You Legally Buy a Real Human Skeleton? – Online Web Gyan wrote on 22 January 2021:

[…] Specimen of the Week 385: UCL skulls […]

Close

Close

[…] Specimen of the Week 384: UCL skulls (UCL Blogs) […]