Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month November 2017

By Mark Carnall, on 30 November 2017

First halves are overrated. Be it team sports, plays, movies or books, the first half sets the scene, introduces the characters, gets the ball rolling but it’s really the second half which delivers the climax, the conclusion, the crescendo, a twist, the point or the moral. A good second half will stick with you, make you think. You’ll never get last minute drama, an eleventh hour save or a Cinderella story in a first half. It’s all about the second half. The same is absolutely not true of fossil fish at all. There’s tail fins, sure, but it’s all about what’s up front for fish. I don’t even know why I raised it in the first place really. But now you’re thinking about how cool the second half of things are and well, it’s not gonna be the case in this month’s underwhelming fossil fish, our periodic foray into the fossil fish collections of the Grant Museum of Zoology. Break your hopes down, here’s this month’s fossil.

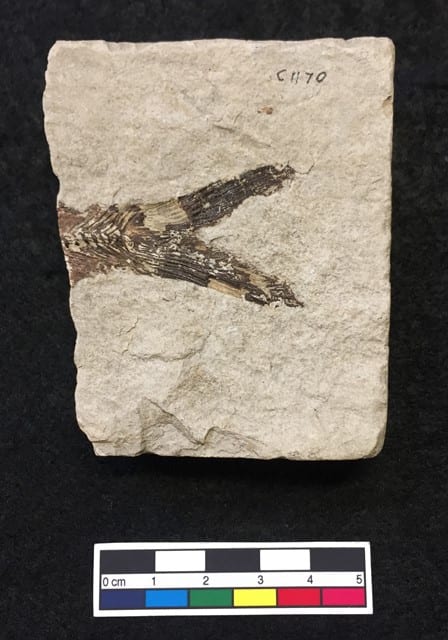

What happened to the rest of this fossil? The Grant Museum records do not record whether there ever was a front end to this fossil. It may have been that the rest of the fish was never preserved due to a quirk of fossilisation. It may be that the head end was destroyed with a misjudged whack with a geological hammer leaving just the tail. It may be that the head has been wrongly attached to a bandicoot, unlikely, but it happens. It seems that this less-than-half tail end is the whole story for this month. This specimen came with an array of identifications from Grant Museum curator Tannis Davidson. According to the database, this is identified as Diplomystus sp. collected from Lebanon. According to an old card index this is a specimen of Diplomystus brevissimus and according to an older catalogue of fossils, this is a specimen of ‘to be identified’. Taking the most specific identification at face value (for reasons we’ll see later) Diplomystus brevissimus is an older name for Armigatus brevissimus. Armigatus brevissimus and relatives are some of the most studied teleost fossil fish, however, the fine detail of the relationship between various fossil species is complicated with a number of concurrent classification systems recognised (Grande 1982). Armigatus brevissimus was a herring-like fish from the Upper Cretaceous of Lebanon which checks out with one of the three documentation sources in the Grant Museum (although we can’t be sure if the locality wasn’t later ascribed to the fossil from the identification rather than the other way around).

Preservation Well, there’s clearly a few bits of the fish missing here, almost everything from the tail forward. Although the fossil looks very much like a fish tail, the margins of the tail fins and back and underside of the body are missing as you can see from the truncated fin rays of the tail. There is exceptional detail preserved in what is left of this individual which is consistent with the preservation at the Konservat–Lagerstätte (site of exceptional fossil preservation) al-Namoura in Lebanon. The fine detail of the vertebra can be seen as well as the individual fin rays of the tail as well as where individual rods have come away with the counterpart to this fossil.

Scientific Research As mentioned above, despite this species and its fossil relatives being used extensively in anatomical studies and comparisons, their relationships are decidedly messy. These fossils were first named Clupea brevissimus in 1818 but were later moved to Diplomystus, in 1888. Diplomystus was coined by Edward Drinker Cope in 1877 (of ‘Bone Wars‘ fame). In 1982 the entire genus was revised by Grande and Diplomystus brevissimus was moved into Armigatus brevissimus on the basis of a tooth patch on the skull, morphology of the skull elements and a foramen (hole) in one of the gill arches. This is why we can’t confirm the true identification of this specimen as we’re lacking these diagnostic features so unless the other end of the specimen is found we’re going to be stuck with this tentative identification FOR THE REST OF TIME.

In Society Being in the fish tail ballpark let’s take some time to address the issue with mermaid/man/folk tails. Most fish (excluding all the weird ‘uns) swim with their tails and fins in the same plane as their body (dividing left and right) and move their tails from left to right to propel themselves. Most depictions of merfolk show the tail fins perpendicular to the plane of body (dividing front and back) so merpeeps can sit on a rock without looking too uncomfortable. If they swam like fish, this would mean that they should swim on their sides rendering them completely blind on one side of the body as both eyes face the same way, unless of course mermaids spend all their time on the bottom of the sea like flounder, turbot, dab and sole. Whales and dolphins, which are mammals, not fish, have their tails in the same orientation as merpeople. However, most mermans are depicted with scaly and shimmery lower halves which is a fish character, not the smooth skin of a cetacean (whales and dolphins) but female mermaids are often adorned with kelp or scallops to cover their very mammalian breasts which is one of the mammal characteristics. This leads us to a number of possible evolutionary scenarios explaining merfolk:

1) Half human fish whose axial skeleton have rotated 90 degrees through evolution.

2) Half human cetaceans who have secondarily evolved shimmering scales

3) Half fish humans which have evolved a primate-like upper body.

4) Half cetacean humans which have evolved a primate-like upper body.

5) Completely their own thing which have convergently evolved fish, human and cetacean characteristics.

Scenario 1 is not likely as this would require humans evolving morphologies superficially similar to animals which are distantly related to them. Scenario 3 makes slightly more sense but there are so many convergences required between fish and humans (depending on the fine detail anatomical similarities) including a number that don’t make sense: noses, ears, nipples, belly buttons, hair, cranium, heterodont teeth etc. Scenario 4 is still quite ridiculous but logically less of a stretch than we propose for 3 as long as we’re happy with the re-evolution of scales (pangolins did it!). Alternatively humans evolving cetacean-like lower halves is probably the most plausible. Scenario 5 demands the most stretching of possibility and plausibility. So, pending further research, merpeople are probably descendants of whales and nothing to do with fish.

Armigatus brevissimus

Preservation 8

Research 3.5

In Society 1

Underwhelmingness 5

References

Grande, L. 1982. A Revision of the Fossil Genus Diplomystus, With Comments on the Interrelationships of Clupeomorph Fishes. American Museum Novitates. Number 2728, pp. 1-34, figs. 1-38.

Mark Carnall is the Collections Manager (Life Collections) at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and former Curator of the Grant Museum.

2 Responses to “Underwhelming Fossil Fish of the Month November 2017”

- 1

-

2

Susan Elaine Jones wrote on 8 December 2017:

Superb UFFotM this month, not just for the excellent informative content,, the deep consideration of merpeeps evolution but also the links to Bandicoots and Bone Wars are worth the subscription price alone!

Close

Close

True to form, what a delightful 180 in the second half