Racism, eugenics and the domestication of humans

By Subhadra Das, on 25 October 2017

The Grant Museum’s current exhibition – The Museum of Ordinary Animals: The Boring Beasts that Changed the World - explores the mundane creatures in our everyday lives. Here on the blog, we will be delving into some of the stories featured in the exhibition with the UCL researchers who helped put it together.

In December 1863, the scientist Francis Galton presented a paper to the Ethnological Society entitled ‘The Domestication of Animals’. In it, he outlined six characteristics necessary for an animal to be domesticated

- Hardiness: the ability to survive despite human neglect.

- Fondness for Man…notwithstanding occasional hard usage and frequent neglect.

- Desire of comfort…a motive which strongly attached certain animals to human habitation.

- Usefulness to Man.

- Breeding freely.

- Easy to tend…by which large numbers of them can be controlled by a few herdsmen…Gregariousness is such a quality.

It is worth noting that this paper was presented not to an audience of scientists who study animal behaviour but to ethnologists – that is, scientists who study the difference between different groups of people – and that Galton’s main objective in outlining these traits was to demonstrate that domestication happened because certain species of animals were, by their inherent nature, domesticable.

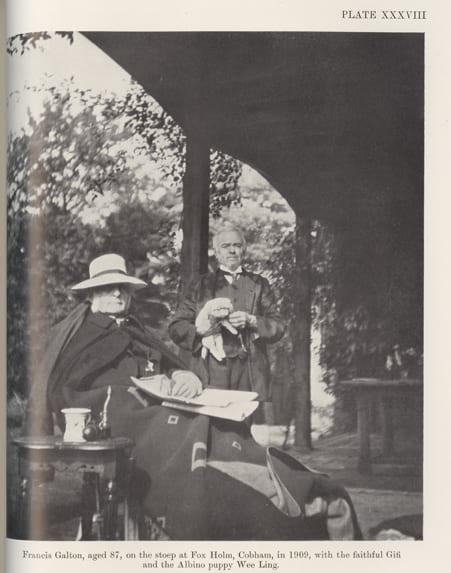

Francis Galton and his albino Pekingese dog Wee-Ling, whose skull features in the exhibition. Wee Ling was the product of research into pedigree breeding by fellow eugenicist Karl Pearson.

Where a particular species does not have the traits to be brought under human control, he said, less civilised human societies, such as the reindeer herders of Lapland, are forced to live their lives to accommodate the animals in order to benefit from them. Galton gives examples from all over the world of how what he called the “rude races” had successfully brought animals under their control as pets, sacred animals and in zoos. In other words, it is easy to domesticate animals — even ‘savages’ can do it.

Galton’s The First Steps towards the Domestication of Animals was published in 1865 and that same year he also published a two-part article entitled “Hereditary Talent and Character“, in which he outlined his vision for improving society through the selective breeding of humans. Galton’s particular genius was to think of humans as Ordinary Animals too. In the wake of his cousin Charles Darwin’s theory of how species evolved, Galton reasoned that if humans are a species like other domesticated animal species, there is every reason, and moral and political imperatives to suppose that humans can also be bred in such a way as to improve the species.

Over the next five decades Galton developed this idea and called it eugenics (‘eu’ = good, or true + ‘genus’= birth, race or stock). Adopted across the political spectrum in the US, Britain and Europe in the early decades of the Twenieth Century, and by the Nazis in the 1930s, Galton’s idea was put to devastating effect.

Galton used the success of animal domestication and husbandry to justify his idea for a eugenic state. “No one, I think, can doubt,” he wrote “that, if talented men were mated with talented women, of the same mental and physical characteristics as themselves, generation after generation, we might produce a highly bred human race, with no more tendency to revert to meaner ancestral types than is shown by our long-established breeds of race-horses and fox-hounds.”

To determine what those mental and physical characteristics were, Galton turned to the study of anthropometry, or the science of measuring of human abilities. In 1884 he established his Anthropometric Laboratory at the International Health Exhibition in South Kensington. Over the course of one year, nearly 10,000 people paid 3 pence a time to have their height, weight, eye colour, vision, strength of grip and hearing measured and recorded. One of the devices Galton designed to test human hearing was a whistle which could be varied in pitch to such a degree that in the upper ranges only animals could hear it. He tested the whistle on animals in London Zoo “but with little to report, except that it certainly annoyed the lions.”

The modern dog whistle was originally invented by Galton to test human hearing – one of the many characteristics he used to measure human qualities.

(UCL Science Collections LDUCGC-GALT-39)

Galton’s attitude forces us to address: how are humans different from animals? What do we mean when we talk about humanity? If humans are a species like any other, what imperatives do we have for treating ourselves (and them) differently?

The Museum of Ordinary Animals runs until 22nd December. A number of events accompany the exhibition: through discussions, a late opening, a comedy night and offsite events discover how boring beasts shape our relationship with the natural world. Full details are on the exhibition’s website.

Subhadra Das is Curator of the UCL Galton Collection, and contributed to the Museum of Ordinary Animals.

Close

Close