Specimen of the Week 313: The Newt Microscope Slides

By ucwehlc, on 20 October 2017

This week, lucky blog readers, not only do we have our usual Grant Museum Specimen of the Week, we have a super-special guest star. From the Grant Museum Micrarium and the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons come…

**The Newt Microscope Slides**

Newtmageddon

I was admiring the Grant Museum Micrarium recently (as I often do), and one of the microscope slides caught my eye. It shows a series of microscopically thin slices through the body of a larval (immature) newt. This sort of slide is common in our collection: there are at least 10 of them in the Micrarium alone. There is no information on the slide itself, but from the techniques and materials used it seems to have been made during the 20th century. We also know that it would have been used by UCL students, as it originally came from a cabinet of microscope slides from the UCL Zoology labs.

This slide and others like it have been used to teach anatomy and microscopy to students for a very long time. Newts have also been an important model organism (an organism extensively used in laboratory experiments) for even longer. Our newt reminded me of some other microscope slides used to teach students, which are much, much older.

Salamandapocalypse

These newt slides (pictured below), now in the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons, were made for the brilliantly-named Dr Tweedy John Todd as part of his experiments into healing and regeneration sometime in the 1820’s or 1830’s. For those of a microscopical bent it is worth noting that these slides are some of the oldest surviving examples of the use of Canada balsam as a mountant. Dr Todd was one of the first people to study the importance of nerves in the healing process and published his results in the snappily-titled On the Process of Reproduction of the Members of the Aquatic Salamander in 1823. As you may have guessed from the title, Dr Todd made his historically important medical discoveries by cutting the legs off newts. Lots and lots of newts.

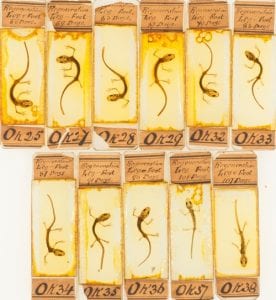

Newt slides from the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons. rcsms-Quekett-division 2-Ok 25-38 © Royal College of Surgeons

The exciting career of these particular newts did not stop with Dr Todd’s death in 1840. They came to the attention of Richard Owen and his assistant John Quekett at the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. Owen is now famous for his opposition to Darwin and for founding the Natural History Museum, but at the time was the Conservator of the Hunterian Museum. He was working with microscopist Quekett to develop a teaching collection of microscope slides for the Royal College of Surgeons, and Dr Todd’s slides were just the ticket.

Model organism

Newts and other salamanders have fascinated humans for thousands of years due to their ability to regenerate lost limbs. They have often been used in laboratory experiments, especially axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum) which are particularly good at regenerating organs and are used by researchers in the study of nerve regeneration and transplant medicine. You can read more about axolotls on our previous blogs here and here.

Although there is a large population of captive bred axolotls in labs around the world they are now critically endangered in the wild. Today all three species of newt found in the UK are protected by the Wildlife and Countryside Act, and the great crested newt Triturus cristatus is also a European Protected Species. Like the wild axolotls they are threatened not by overenthusiastic medical researchers, but by habitat loss.

You can find out more about the importance of model organisms in our current exhibition The Museum of Ordinary Animals which runs until 22nd December. The Grant Museum of Zoology is open from 1–5pm Monday to Saturday. Admission is free and there is no need to book.

The Hunterian Museum is currently closed until 2020 for renovation, but you can follow the work of the Royal College of Surgeons museums, library and archive team through their blog.

Close

Close