Why natural history museums are important. Specimen of the Week 278: The British Antarctic Survey Limpets

By Jack Ashby, on 10 February 2017

There is much more to a natural history museum than meets the eye, and that’s mostly because relatively tiny proportions of their collections are on display. At the Grant Museum of Zoology we are lucky enough to have about 12% of our collection on display. That’s because we have a lot of tiny things in the Micrarium and our collection is relatively small, with 68,000 objects. While we REALLY like to cram as much in our cases as is sensible, these percentages are not realistic for many museums, whose collections run into the millions.

The vast majority of specimens in natural history museums, ours included, were not intended for display, and that includes this week’s Specimen of the Week…

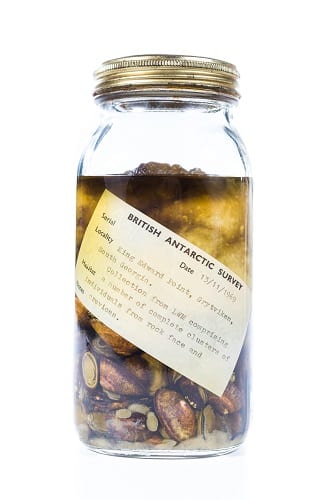

**The Jar of Antarctic Limpets**

What are museums for?

The value of natural history displays are relatively well documented. In 2013 I oversaw a study funded by Arts Council England for the Natural Sciences Collections Association which found that they were the most popular gallery type in museums with mixed collections. It’s clear that what visitors see of natural history museums is very well loved. And there are other reasons to think museums are important: research going on here in our own department – UCL Culture – is investigating the benefits to people’s health and wellbeing from engaging with museums. However, arguably many natural history museums could be more successful at using their galleries to communicate what goes on behind the scenes, and that’s a shame as public galleries are not the only thing museums are for.

Specimens or artefacts?

As well as being visitor attractions, many museums are also research institutes – there may be tens or hundreds of scientists working behind the scenes, using the stored collections to make discoveries about biodiversity, evolution and how ecosystems work, among many other things. If they don’t have their own researchers on staff, most museums with natural history collections hold the bulk of their collections off display for researchers to visit. In natural history museums we talk of “specimens” rather than “artefacts”, which are more often associated with archaeology, anthropology and social history museums. The difference is that specimens are real examples of a particular type of thing: specimens are in museums to represent their whole species. Artefacts are man-made objects, mostly in museums to represent themselves*.

Specimens as snapshots

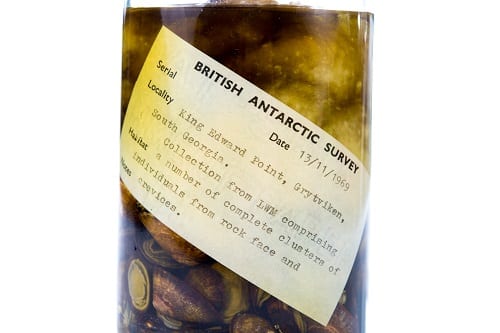

There are many kinds of research that can be done with museum specimens, not least because museums hold the physical definitions of each species : the type specimens. Specimens are not just an example of a species, they are an example of a species at a particular place at a particular time. As crucial as the object itself are the data that go with it: where was it collected, when, and by whom. These pieces of information make museum specimens incredibly valuable. These limpets, for example, were collected at King Edward Point in South Georgia on 13th November 1969, by the British Antarctic Survey.

Understanding changes in diversity

One of the most critical kinds of research that natural history collections can be used for is investigating how ecosystems and their ecological communities change over time. This specimen is physical evidence that this species of limpet was at that site on that date. Furthermore, analysis of the make-up of the specimens could tell us about the chemistry of the ocean they lived in. Understanding the impact of climate change, pollution, ocean acidification and ecosystem collapse being are critical to our ability to mitigate these global challenges, and specimens like this can provide invaluable data.

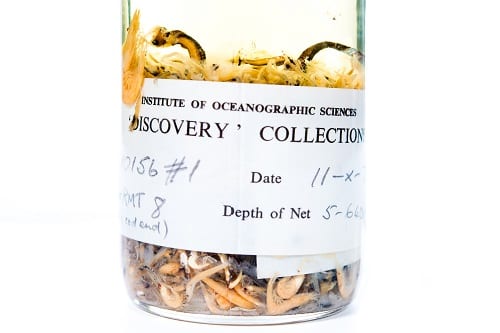

Series sampling

Different scientific organisations have been sampling at King Edward Point since 1925 (although it was somewhat disrupted by the Falklands War, after which it was occupied by the British military for a while). Therefore, the specimens from different points in the long term sampling series can be compared over time. We also have samples from the Institute of Oceanographic Sciences (now the National Oceanography Centre) that have been amassing “The Discovery Collection” since 1925. The original purpose of this survey was for whaling research, and so they trawled for huge numbers of samples of krill – the principal food of whales. As such they can tell us about the oceans before the whaling industry brought about the collapse of global whale populations.

These are just a couple of examples of the kinds of incredibly valuable collections that museums hold in their storerooms. Museums are so much more than just the displays.

* That said the extent to which specimens are also artefacted by human intervention is one of my favourite topics when talking to students about the authenticity of museum displays. Mounted skeletons and taxidermy, for example, are made by people from animal remains. I wrote about this in The Conversation.

Jack Ashby is the Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

2 Responses to “Why natural history museums are important. Specimen of the Week 278: The British Antarctic Survey Limpets”

- 1

-

2

Kim Bryan wrote on 24 February 2021:

Fancy becoming a citizen of the western antarctic?

Founded on 2nd November 2001 as a new nation project, the mission of Westarctica is to bring attention to a remote uninhabited region central to the stability of the ecosphere of our planet. Westarctica enjoys non profit tax exempt status in the US, non consultative status with the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs and operates consular offices around the world including in the UK. Seeking to become the global voice of a region with no independent role in world affairs, Westarctica is fully supportive of all international efforts to conserve the West Antarctic ice sheet.

https://www.westarctica.info/

Close

Close

I am very pleased to see this article. In my opinion Mollusks play vital role in biodiversity, geography, evolutionary biology to find out various previous Physical aspects to related our ocean environmental changes as well as to find out link with other animal association over time and to find out habitat with environment.

Thank you for sharing 🙂