Specimen of the Week 242 – the Marsupial Lion

By Jack Ashby, on 3 June 2016

1) Large lion-shaped predators were living in Australia until around 50,000 years ago – lion-shaped, but not lions. This is because there were no wild cat species in Australia*, and up until 3-5000 years ago when the dingo arrived with Polynesian traders, all large Australian mammals were marsupials. One such beast was Thylacoleo carnifex, the “marsupial lion”. Alongside this big predator lived “marsupial rhinos” (diprotodons), giant kangaroos, giant echidnas, “marsupial tapirs” (Palorchestes) and giant wombats (Phascolonus). All in all, Australia used to have much bigger animals than it does now.

2) It is believed that marsupial lions diverged from the branch of the marsupial tree that led to wombats and koalas. It’s also possible they were more closely related to possums, but in any case this is interesting as it’s unusual for carnivores to evolve from herbivores. Along with wombats, possums, koalas and kangaroos, the marsupial lions belonged to the order Diprotodontia, which is characterised by two big forward-facing lower incisors (Di: two, proto: forward. dontia: teeth). In Thylacoleo, these essentially functioned like a cat’s canines, but they were serrated.

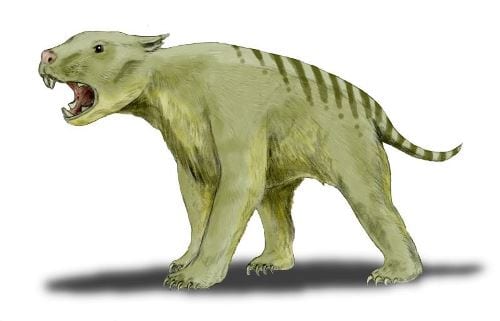

Reconstruction of the marsupial lion, by Nobu Tamura, CC-BY-3.0; via Wikimedia Commons

3) In an even closer example of convergent evolution (when two unrelated lineages evolve similar adaptations to fulfil the same task, like those puncturing predatory front teeth), Thylacoleo had extraordinarily well developed carnassial teeth – the long slicing blade-like cheek-teeth very similar to what is seen in big cats. This is essentially the key defining feature of a marsupial lion, and it has always struck me as remarkable that this is exactly the part of the animal that was preserved in this fragmentary fossil we have in the Grant Museum. It’s just a small section of jaw, but the slicing premolar carnassial has survived.

4) This fossil was collected when a well was sunk 40 miles from the town of Hay in rural New South Wales. The local Aussie Rules football team is the Hay Lions, which I choose to speculate is no coincidence. We don’t know when this fossil was excavated, but Thylacoleo was one of the first extinct mammal species described from Australia, by Richard Owen in 1848. As much as I dislike pretty much everything about Owen**, I do have to credit his choice of name. Thylacoleo carnifex – “the pouched lion executioner”.

5) Thylacoleo had a retractable thumb claw (again, convergent with cat claws), which has long been used as evidence of its predatory prowess. Earlier this year evidence was found in a cave that suggested they were competant climbers (indeed, that thumb is semi-opposable), leading to the suggestion that they were ambush predators – jumping out of trees to attack passing prey. The timing of Thylacoleo‘s extinction is suspiciously close to the arrival date of the Australian Aboriginal people (and in many proposed scenarios this was a significant factor in their demise). The fact that they probably lived side by side made me wonder whether marsupial lions dropping out of trees could have started the age-old Australian yarn of the drop bear. The threat of drop bears has long been the first choice tale for gullible tourists, but maybe it has its roots in the marsupial lion.

*until Europeans introduced domestic cats after their colonisation in 1788, which have since gone feral and represent one of the greatest biodiversity disasters in the world.

** As well as being one of Europe’s leading comparative anatomists, founding the Natural History Museum and inventing the word dinosaur, he also had a big role to play in seriously damaging the career of our own founder, Robert Grant. He was, by any account, a thoroughly bad egg.

Jack Ashby is Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

[UPDATED 10/10/2016 to correct a typo in the date of European colonisation – the correct date is 1788.]

Close

Close