Please don’t call us a Cabinet of Curiosity

By Jack Ashby, on 12 February 2016

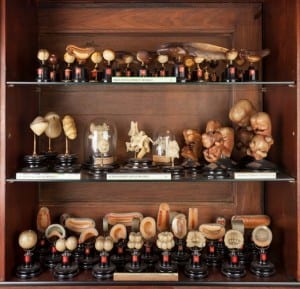

Embryological wax model display at the Grant Museum.

Top: Frogs; Middle: Arthropod, Echinoderm, Human; Bottom: Lancelet

“Isn’t the Grant Museum wonderful! It’s such a cabinet of curiosity!”

This exclamation is clearly meant as a rich endorsement of the Grant Museum – it’s obviously intended as a compliment. Nevertheless, it makes me wince.

Inspiring curiosity and wonder is surely among the highest ambitions a museum could ever have. It’s infinitely more important than making visitors learn something. Curiosity? I am a huge fan. Cabinets? We definitely have some nice ones. Cabinets of Curiosity? No thanks.

For me, this term implies that our objects are nothing but curios – weird artefacts amassed by some eccentric collector. Erratically accumulated in another time; weird and wonderful titbits intended to impress; to show off the collector’s status and influence – “Gosh, Sir William! Where did you get that ghastly tenrec!?”

Not to say that other disciplines do fit that description, but I think the phrase Cabinets of Curiosity – and Wunderkammer like it – are especially bad fits for natural history. It’s not that I’m saying we should be particularly pious about the real world contributions that natural history collections have to support world-changing science*. I’d be the first to admit that dead animal specimens can be funny, and beautiful, but they are also important.

It’s not that the randomness implied by Wunderkammer offends recent leaps that museums have made in professionalising curation. That could surely be part of it, but I don’t want to go on a tangent about how organising isn’t the same as curating (which has been well covered on this site). It’s that the term suggests that our collections are irrelevant today – nothing but a sophisticated side-show. Perhaps not even that sophisticated.

The Micrarium at the Grant Museum inspires curiosity and wonder

I’m aware that not all of my colleagues agree, and some have even embraced it. I understand that for some it might feel like an attractive proposition, but I do think it undermines the importance of museums.

To be clear, I absolutely subscribe to our collections being objects of wonder. My office is on the balcony directly above our Micrarium. Every day I hear “Wow!” (a tick for wonder) “Look at this! What is that!?” (ticks for curiosity). And that gives me a warm glow inside.

But I’m left very uncomfortable at thinking we are working so hard to attract people to ogle at curios. Another word that museum professionals avoid is “weird” (and I know at least one museum’s communications strategy explicitly forbids it), for entirely the same reasons – museums shouldn’t be getting public support to maintain curios and weird trinkets.

Dog with eight legs – I don’t think we have the context in our displays to avoid this being chiefly a curio. LDUCZ-Z1529

I am aware that it wouldn’t take the greatest leap to accuse me of hypocrisy here. Why do we make such a show of things like our Jar of Moles? It would be absurd to insist that the moles are not weird, and it is my decision to make them a public spectacle. On other hand, I’ve ruled out displaying our teratological collection – anyone who spots it in our store room asks why the dog with eight legs isn’t on display. “Surely the people would love it!?”

The line is hard to draw, but the moles clearly communicate the Grant Museum’s history as a university collection – we assume they were stored in this way as they were intended for a dissection class, or by a researcher planning to study mole anatomy (thus requiring easy access to multiple moles). The wonder a visitor feels when they meet the moles – and inevitably asks the question WHY do we have a jar of moles – hopefully inspires them to ponder why a university would want to have any of our objects. “What is this museum doing here?” is a perfectly good, curious question; one we encourage.

There surely is a way of displaying an eight-legged dog without conjuring the traveling Freak Show, but right now I don’t see the appropriate context within our current displays. I worry that it would be too much of a curio, not enough of an object of wonder.

In many ways Renaissance Cabinets of Curiosity were the precursors to museums. They held art, zoological and geological specimens, archaeological and anthropological finds and other travellers’ spoils from across the globe, largely before any of these academic areas really existed. Indeed, what I’ve argued is the best natural history specimen in the world – the Oxford dodo – was essentially part of a cabinet of curiosity, before Tradescant’s collection was acquired by Elias Ashmole. It went on to be the basis of the Ashmolean Museum, arguably the first public museum in Europe.

But today the academic disciplines mentioned above do exist, and we do use our collections in interesting, valid, useful, relevant, important, wonderful ways. So I ask you a favour, please don’t think of our museum as a Cabinet of Curiosity – I think we are so much more than that.

*climate change, biodiversity, food availability, energy and medicine to name a few.

Jack Ashby is Manager of the Grant Museum of Zoology

9 Responses to “Please don’t call us a Cabinet of Curiosity”

- 1

-

2

Thomas H wrote on 12 February 2016:

I agree with the main point of this article – weirdness for the sake of weirdness is not what museums are for. But to be fair to Ole Worm, whose museum you have figured as the archetypal cabinet of curiosity (that same picture sits by my desk), his aims were far higher than a simple freak show.

Not only did he categorise and arrange things in a way which, although outdated by modern ideas, fit the then understanding of the structure of the world. Like the other Wunderkammers that sprung up at the same time, it was part of the general concept of the microcosm and the macrocosm – that a room, city, or even person (although Worm was not a Paracelsian) could be a complete and miniature representation of the world.

In fact, his ideas about how people should interact with museums focussed more on what we could learn than the pure shock of the freak. He wrote (in Latin):

“I conserve well with the goal of, along with a short presentation of the various things’ history, also being able to present my audience with the things themselves to touch with their own hands, and see with their own eyes, so that they may themselves judge how that which is said fits with the things, and can acquire a more intimate knowledge of them all.”

-

3

Ray Barnett wrote on 12 February 2016:

Jack,

I appreciate your sentiments but for me an even greater bête noire is how no report in the media about museums is complete without the prefixes ‘musty’ or ‘dusty’. If somehow we could abolish this cliché we would be doing the museum world a great service.

- 4

-

6

Jenn Steenshorne wrote on 12 February 2016:

To do so is completely ahistorical and misunderstands the purpose of Cabinets of Curiosities and Wunderkammers (many were not just collections of weird stuff for the sake of having weird stuff).

-

8

Richard Kissel wrote on 13 February 2016:

Any and every collection of natural history is an assemblage of curiosities, but it is the context in which they’re presented that lifts them beyond mere curios. Context–like that you provided for the pup a few posts above–helps visitors create meaning beyond the sideshow. I love the Grant, but pup or no pup, context is lacking, and it’s a wonderful curiosity cabinet. Embrace it!

-

9

Amanda wrote on 28 August 2022:

Curiosity cabinets are the elder to your collection and are exactly what you have. Natural history is prime example of curiosity, please do more research and show respect and education to the field, the concept of curiosity cabinets was to display conversation pieces for educated people to converse about, to assume less and use language to discredit curiosity shows exactly why it’s important to go back to the roots and have both, museums are great for preservation, not exploration. Please do more research, I’m almost concerned a public place to write incorrect and biased opinions was given due to the topics at hand.

Close

Close

The National Museum of Ireland – Natural History in Dublin is often cited in popular press as a ‘cabinet style museum’ which is halfway to a ‘cabinet of curiosities’ in many commentator’s eyes. Some of the difference between historic cabinets and today’s museums is as much about the audience as the layout or content. People are still curious (a very important trait we encourage), but generally much better informed.

See: Gould, S.J. (1994) Cabinet museums revisited. Natural History Magazine 1/94: 12-20. (Reprinted as Cabinet museums: Alive Alive O! in Gould, S.J. (1996) Dinosaur in a haystack. Jonathan Cape, London, 238-247).