A King as catapult practice!

By Jenny M Wedgbury, on 21 January 2016

Detail of Noel Lemire (1724 – 1801), After Jean Michel Moreau (1741 – 1814), Louis Seize, 1792, Coloured etching, Inscribed: Bonnet des Jacobins donné au Roi 20 Juin 1792 (The Jacobin bonnet of liberty given to the King 20 June 1792); A Paris Chez L’Auteur Rue des Augustins, UCL Art Museum

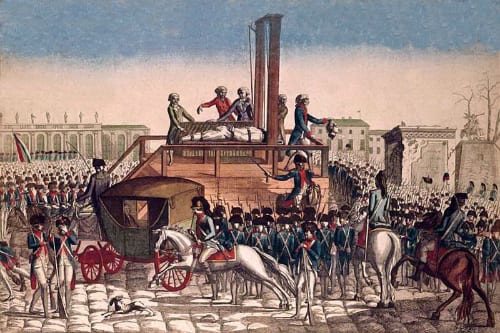

On this day, 21 January 1793, Louis XVI of France, stepped out of a carriage in the Place de la Révolution (formerly Place Louis XV) and climbed the steps to the guillotine.

At eight o’clock that morning, a guard of 1,200 horsemen had arrived to escort the former king on a two-hour carriage ride through the streets of Paris to his place of execution. Accompanying Louis, at his invitation, was a priest, Henry Essex Edgeworth, an Englishman living in France. Edgeworth recorded his experiences of that day stating,

“As soon as the King had left the carriage, three guards surrounded him, and would have taken off his clothes, but he repulsed them with haughtiness- he undressed himself, untied his neckcloth, opened his shirt, and arranged it himself. The guards, whom the determined countenance of the King had for a moment disconcerted, seemed to recover their audacity. They surrounded him again, and would have seized his hands. ‘What are you attempting?’ said the King, drawing back his hands. ‘To bind you,’ answered the wretches. ‘To bind me,’ said the King, with an indignant air. ‘No! I shall never consent to that: do what you have been ordered, but you shall never bind me. . .’”

Cronin, Vincent, Louis and Antoinete (1975); Edgeworth, Henry in Thompson, J.M., English Witnesses of the French Revolution (1938, Memoirs originally published 1815).

The King then climbed then approached his executioners on the scaffold and according to some accounts, the blade fell at 10.22 and one of the executioners showed the head to the crowd, at which point a huge cry of “Vive la Nation! Vive la République!” arose and an artillery salute rang out which reached the ears of the imprisoned Royal family”

From Charles-Henri Sanson’s first-hand account, former royal executioner and then High Executioner of the First French Republic.

The image of the guillotine, the execution of the King and Queen and the subsequent ‘reign of terror’ are often the tableaux against which we set our knowledge of the French Revolution. However, it is often over-looked that following the fall of the Bastille in 1789, Louis XVI nominally presided over the old feudal order of France for three years, whilst the revolutionary cogs turned.

Our current exhibition in UCL Art Museum, Revolution under a King: French Prints 1789 – 92, consists entirely of objects from the first phase of the French Revolution, when Louis XVI was still on the throne. The exhibition follows three central phases of the early years of the French Revolution. The final phase culminates in a display that traces the King’s doomed flight to join with foreign armies at the Austrian border in the Flight to Varennes, the revolutionary invasion of the Tuileries Palace in 1792 and his eventual trial and execution.

Anonymous La Famille des Cochons ramenée dans L’Etable (The Family of Pigs brought back to the Pigsty), 1791 Coloured etching, UCL Art Museum

One image really stands out from this section and seems to encapsulate the narrative of the first three years of the revolution leading to the steps of the guillotine. It is the intriguing and beguiling image of Louis Seize, by Noel Lemire after Jean Michel Moreau. This coloured etching is adapted from a print after a formal portrait of Louis XVI made in 1775, and then altered in the plate to add the bonnet rouge (the symbol of revolutionary zeal). It is also a commemoration of the journée of the 20th June 1792, which, by no coincidence, falls upon the anniversary of the Flight to Varennes in the previous year. On this day, a crowd of revolutionary supporters invaded the Tuileries Palace where the royal family were confined. They confronted the King directly, forcing him to wear the revolutionary cap of liberty and toast the Republic, a personal humiliation and a further stage on his rapid progress towards demise.

Noel Lemire (1724 – 1801), After Jean Michel Moreau (1741 – 1814), Louis Seize, 1792, Coloured etching, Inscribed: Bonnet des Jacobins donné au Roi 20 Juin 1792 (The Jacobin bonnet of liberty given to the King 20 June 1792); A Paris Chez L’Auteur Rue des Augustins, UCL Art Museum

In the print, the head has been carefully cut around and the background eliminated. A possible reason for this can be found in a close examination of the paper behind the King’s neck. It has a number of furrows, which reveal that the head has been folded back many times. This suggests the possibility that the King’s head was used as target practice for a catapult or the pellets of a toy gun!

To find out more about the exhibition and our public programme of events please go to Revolution under a King

Jenny Wedgbury is Learning and Access Officer for UCL Art Museum

Close

Close