A gem of an idea

By Rachael Sparks, on 26 February 2014

Every collection has its nooks and crannies, and it’s rare for curators to know the full scope of their domain. So every now and again we’ll take a quiet moment to sneak into our stores and explore that neglected corner or unfamiliar drawer, just to see what might be lurking.

Late last year I was looking for some material for my new conservation volunteers to work on. I’d begun training them in the mysteries of plastazote cutting – that’s making snug little foam housing to hold objects safe – and I wanted some simple starter objects. You know the sort of thing: nice and flat on the underside, so there’s no tricky shaping of the mount to match the curve of the object, and not so fragile that the students get disheartened by accidentally breaking something. We’d already done a batch of cylinder seal impressions (straight rectangular lines, flat as a tack – lovely). But now I wanted to try them on something new.

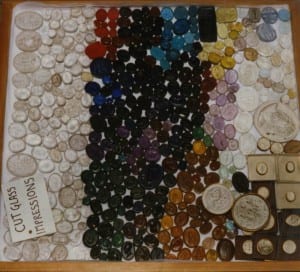

So I started to explore the stores in search of inspiration. Here’s what I found:

Now at first sight, this drawer would depress any curator. Its badly overcrowded, filled with unmarked, unaccessioned objects, and its sole source of documentation is the rather unhelpful (and inaccurate) label thrown in on top. But for me, it was just perfect; a real gem of a find.

What we have here is a series of glass objects, mostly oval in shape, with various classically-inspired designs carved into their upper faces. Most are what we would call intaglios, but a few are carved in cameo as well. These are small, very personal objects you can hold in the hand, in varying shades of amber, red, purple, green and white. Smooth, tactile and aesthetically very pleasing.

So I handed the drawer over to my volunteers for repacking; it went down a treat. And in the process, volunteer Yuqi, noticed another interesting feature – some of the gems have tiny inscriptions cut into their faces, in English or Greek script. This led to much peering with magnifying glasses and cries of delight as we hovered over her work and tried to make out the designs and signatures, most of which seem to be cut in reverse.

So what do we know about this material?

These ‘gems’ (I don’t really know what else to call them) had come to us from the former Museum of Classical Archaeology at UCL, which was disbanded in the late 1990s as the result of some as-yet unexplained need of the higher powers to swallow up their gallery space. The Institute of Archaeology inherited their collections, and so the gems came to live with us.

Unfortunately, that about all I know. The ‘gems’ have never been accessioned, and there isn’t any documentation relating to them. So where they came from, and how and when they came to UCL, is completely unknown. Did they form part of a single collection, or were they given to the museum in dribs and drabs? And what were they brought here for? I’d love to know whether someone actually wanted them for teaching, or whether they were just offloaded onto staff because they had nowhere else to go.

Whatever their history, they served their immediate purpose of training my students, and many of them have now been safely rehoused in conservation grade materials. But this isn’t the end of their story.

You see, now that I know this material is here, I can see its potential. But in order to do something with it, some serious research is in order.

Some preliminary poking about suggests that we have classically-inspired pieces made to cash in on the popularity of ancient gems, perhaps as early as the late 18th century AD. The inscriptions are most probably the maker’s names. Now I want to know who these makers were, why the objects were made, and what the iconography used represents. One big question is whether these are the finished product, sold as a seal for making impressions (remember those names in reverse), or whether these were perhaps used for making plaster casts for sale.

Having been drawn into the story of our gems, I now see similar material everywhere – from collections at the British Museum, to isolated pieces for sale on ebay or in the counter-top displays of Covent Garden antique dealers. Then there is the fabulous gem research being done by Claudia Wagner and her colleagues at the Beazley Archive, in Oxford.

Fortunately, I’m not the only one who is fascinated by our glassy friends, and the same volunteer whose eagle eyes spotted the inscriptions has now decided to write her Masters dissertation on the collection. Hopefully she can pull together some useful parallels and start to put this material in its wider context. The questions are endless: I’m really looking forward to finding out some answers.

_________________________________________________

Rachael Sparks is Keeper of the Institute of Archaeology Collections, UCL

2 Responses to “A gem of an idea”

- 1

-

2

Rachael Sparks wrote on 5 March 2014:

Nice to hear from you Ian – and thanks! I’d certainly love to hear your thoughts on the pieces when you have time – do you want to email me directly about organising a visit?

Close

Close

Great post Rachel,

I’m doing my PhD on actual Roman gems from Britain. I think a lot of what you have are known as ‘Tassies’, glass replicas of ancient gems. But there seem to be some gem impressions, perhaps of ancient gems?

They might have been used in teaching classical art, since they are nice and small and easy to pass round. At the University of Leicester we have a big case of impressions of gems from the British Museum collections, which were acquired for teaching ‘back in the day’.

If you or your masters student wants someone to take a look at them, I’d be happy to give you a hand.