Petrie Menagerie: The Crocodile

By Edmund Connolly, on 13 September 2013

We have covered birds, insects, reptiles and mammals and we now end on an animal prevalent in both land and water, perhaps one of the most iconic Egyptian animals about. The Nilotic crocodile is the second largest in the world and can measure in at a hefty 6.1 metres, a worthy beast for our Petrie Menagerie.

Petrie Menagerie #7: The Crocodile

As a native inhabitant of Egypt it is not surprising these creatures are found in numerous literal and more mythology inspired presentations:

Also, the crocodile appears in hieroglyph, as the human-crocodile hybrid god Sobek and is one of the three elements of the fearsome monster, Ammit, the devourer of souls.

For the 19th / 20th century viewer, crocodiles were recognised, and have even been displayed in menageries prior to ZSL. This is well attested by Lewis Carroll’s philological parody poem, referencing the little critters:

How doth the little crocodile

Improve his shining tail,

And pour the waters of the Nile

On every golden scale!

How cheerfully he seems to grin,

How neatly spreads his claws,

And welcomes little fishes in

With gently smiling jaws!

(Carroll, Alice in Wonderland, 1865)

The Object:

The word crocodile derives from the Ancient Greek: kroko (“pebble”), deilos (“man”); its very name implies a hybridisation. Despite the lovely wooden crocodile presented above, it is the fearsome mixed creature Ammit I shall focus on today.

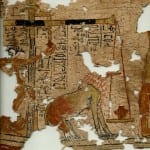

Made up of crocodile, lion and hippo this demon is the perfect climax to our menagerie. In Ancient Egyptian religion, it was believed that if the deceased’s heart was heavier than the feather of truth they had led an untrue life, thus were devoured by this incarnation of the three most fearful Egyptian creatures. This papyrus, an Egyptian substitute for paper made of papyri reeds, depicts the entire judgement scene[1], with Ammit waiting, no doubt hungrily, by the heart as the scales are set.

Petrie’s Peers:

Whilst crocodiles were merrily swimming through the Victorian imagination, what would they make of these more fearsome amalgamations of creatures? Ammit is clearly monstrous, and it is interesting to note the artist has made no attempt to fuse the three animal forms together: each stands out separately, denoting his mythological and ferocious status. This idea of monsters from the past seems prevalent in fiction of the time, returning to Alice and Wonderland, Alice meets a Griffon and a Mock turtle, both of which are similar ‘hybrid animals’[2].

In the sequel, Through the Looking Glass, Alice comes across the ‘Jabberwocky’[3] , who is depicted in the illustration as a dragon-bat-bulldog (??) type mix. In the twentieth century, another epic children’s author, Nesbit, invents another hybrid creature, the Psammead[4] who is a sort of snail / monkey type creature from the Ancient East.

These amalgamations often appear in children’s fiction, perhaps because there is an element of childish naivety in their composition, but it implies a mode of reception for creatures such as Ammit. He is a being from mythology (whether it should be termed belief or illustrative is a massive debate and question to ask, far too much for a little blog post[5]) and Carroll’s Griffin and Jabberwocky, and Nesbitt’s sand fairy (Psammead) all mix elements of recognisable creatures into a fantastical melting pot, out of which crawls these monstrous fascinations.

In this sense, would the hippo- crocodile-lion creature Ammit actually ring familiar with the Victorians? He is similar to their own ‘mythology’ and fairy tales, despite the exotic alienism of his component; quintessentially it is a similar construct[6].

Petrie’s Menagerie:

I firmly believe one can have too much of a good thing, so this will be the final instalment of Petrie’s Menagerie. In our publically accessible museum (Tues-Sat 1-5pm) we now have:

- A Hippo – whom we compared to his celebrity counterpart, Obasych,

- A trio of lions with royal connotations

- A petting zoo, including a dancing hare

- A regal horse (plus plumed headgear)

- Some intricate fish and coiling cobras

- A protective scarab and a royal Vulture

- And, finally, a grinning crocodile.

Not bad for a small museum in Bloomsbury!

Edmund works at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology as the Projects Coordinator. He graduated from the Institute of Archaeology, UCL, in 2012 and plays sport for UCL almuni and ULU.

Edmund works at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology as the Projects Coordinator. He graduated from the Institute of Archaeology, UCL, in 2012 and plays sport for UCL almuni and ULU.

[1] Papyrus is a very delicate, brittle material, so unfortunately this piece is not on display. The picture I have included focuses solely on Ammut, there are other characters and text on the other pieces that are well worth seeing.

[2] This just means they are made up of bits of other animals: The griffon, traditionally lion and eagle, the mock turtle is depicted as a turtle with a calf’s head – perhaps a sly nod to the Assyrian sculptures of cow and human composites? (Thomas, 2008, 3).

[3] Am delighted that spellcheck recognises this word!

[4] The actual word Psammead (pro sam-E-ad) contains the phonemes ‘pa’ and ‘dad’, as well as ‘ma’, ‘mom’, ‘mammy’ meaning the creature is also a hybrid of genders and parental roles (Knoepflmacher, 1987, 310).

[5] Karen Armstong’s superb book, A short History of Myth (2006) covers this type of material, and is quite an easy, short read

[6] If you are interested in the Monstrous and Antiquities type discussion, I may be giving a paper at the Monstrous Antiquities conference at the IOA this year, focusing on Nesbit and Near Eastern beings.

One Response to “Petrie Menagerie: The Crocodile”

- 1

Close

Close

actually, l have a question… if psam means a grain of sand (which is lovely, considering that a psammead is a sand fairy), what is the hieroglyph, and meaning, of the second half of the word psammead? l have e.a. wallis budge’s book on egyptian writing, but so far, have had no luck with this. l only recently came across psamtek as the name of 3 kings…