Specimen of the Week: Week Eighty-Four

By Emma-Louise Nicholls, on 20 May 2013

I am SO excited. I moved into a new flat last week and it has a balcony. That isn’t even the exciting part. Whilst I was flat hunting I narrowed the list down from 1230 to four by using a list of non-negotiable criteria (it’s good to know what you want in life), and then crossed off everything that didn’t stand up to the requirements. On viewing day, I was waiting for the estate agent outside property number one, staring up at the balcony when an eagle landed on the railing. In an ‘if it’s good enough for the eagle to sit on, it’s good enough for me to live in’ mindset, I took the flat. Almost there and then. After moving in, I took my first balcony outing and as I stepped out the self-same eagle erupted out of the corner and flew off. It was only then that I realised I in fact have a nest on my balcony, right there- on MY balcony, with three medium sized white eggs in it. WOW! I vowed never to step foot on the balcony again in order not to disturb the eagle and her future offspring and now check on her every evening using a mirror stuck to a spatula, very slowly and quietly inserted out of a window. She’s doing very well and I expect her baby eagles to hatch within the the next week or so. Now completely obsessed with baby animals in general, I thought I’d tell you about one we have at the Museum. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

I am SO excited. I moved into a new flat last week and it has a balcony. That isn’t even the exciting part. Whilst I was flat hunting I narrowed the list down from 1230 to four by using a list of non-negotiable criteria (it’s good to know what you want in life), and then crossed off everything that didn’t stand up to the requirements. On viewing day, I was waiting for the estate agent outside property number one, staring up at the balcony when an eagle landed on the railing. In an ‘if it’s good enough for the eagle to sit on, it’s good enough for me to live in’ mindset, I took the flat. Almost there and then. After moving in, I took my first balcony outing and as I stepped out the self-same eagle erupted out of the corner and flew off. It was only then that I realised I in fact have a nest on my balcony, right there- on MY balcony, with three medium sized white eggs in it. WOW! I vowed never to step foot on the balcony again in order not to disturb the eagle and her future offspring and now check on her every evening using a mirror stuck to a spatula, very slowly and quietly inserted out of a window. She’s doing very well and I expect her baby eagles to hatch within the the next week or so. Now completely obsessed with baby animals in general, I thought I’d tell you about one we have at the Museum. This week’s Specimen of the Week is…

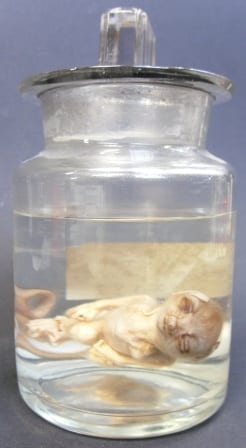

**The Baby (unspeciated) Lemur**

(P.S. I feel I should tell you that it is a pigeon not an eagle)

1) Primates are divided into several groups that range from super easy to ridiculously hard to tell apart depending upon the particular species in hand. For example, apes have the very obvious morphological difference of no tail. As with every rule however there are exceptions, for example the tail-less barbary macaque, which has no tail, is not an ape. Although there are numerous ‘rules of thumb’ I think it’s fair to say that many species invoke the enviable identification trick of ‘just knowing’, to a certain extent. The main non-ape, non-monkey groups are bushbabies, tarsiers and lemurs. Once you get get your ‘eye-in’ for facial shapes and various other qualities, you can begin to see patterns that will allow you to come across a new species of primate and give a pretty good attempt at placing it into a category.

2) As we are not quite sure as to which lemur family our baby lemur belongs, I shall tell you about lemurs as a group. Lemurs are all endemic to Madagascar, although two species were introduced to the Comoros Islands where they have flourished. There are no (modern) species of lemur found anywhere else in the world (I mean in the wild… obviously).

3) There are currently approximately 100 recognised species and subspecies of lemur, although many scientists have been saying for years that there are likely to be many more. To back this up, they went and discovered several species within recent years, indicating (as zoological patterns seem to do) that more are likely to come out of the woodwork. The 100 odd known types include the smallest primate in the world; Madame Birth’s mouse lemur, which weighs only 30g. Awwww. The largest species of lemur is the spectacular indri which weighs up to 9kg. The huge number of lemurs means that the country of Madagascar ranks second in the world for the highest number of primate species. Brazil got the top spot, though with the Amazon fighting in it’s corner, you’d expect nothing less.

4) The word ‘lemur’ comes from Roman mythology. The ‘lemures’ were shades, ghosts, or spirits of the restless or malignant dead. The lemur was named after the lemures owing to their ‘ghostly vocalisations’, the reflective qualities of their eyes and possibly also the fact that many species are nocturnal.

5) For the majority of lemur species, the mating season is less than three weeks each year, the timing for which is directly related to environmental conditions. A single female is likely to be in oestrus for just a few days during this period which causes many a conservationist to pull their hair out. I mean their own hair, not the lemur’s hair in a fit of sadistic rage-filled frustration. The gestation period can be as short as nine weeks in some species but lasts for up to 24 weeks in others. Smaller species tend to have twins, though many have triplets or even quadruplets. Conversely, larger species normally have a single offspring, or twins on occasion. Newborns are vulnerable and are carried in the mother’s mouth of all places until they are old enough to hold on to the fur on the mother’s back. They drink the mother’s milk until the environment causes the next flush of fruit and shoots, when they begin to forage for themselves. They will stay with the mother until they are two years old.

Emma-Louise Nicholls is the Museum Assistant at the Grant Museum of Zoology

3 Responses to “Specimen of the Week: Week Eighty-Four”

- 1

-

2

The Week In Science (May 20 – 26) | Science Communication Blog Network wrote on 1 June 2013:

[…] Specimen of the Week: Week Eighty-Four […]

-

3

Specimen of the Week: Week 109 | UCL UCL Museums & Collections Blog wrote on 11 November 2013:

[…] waved goodbye with a heavy heart to the baby eagles that hatched on my balcony and fledged during the summer, Saruman (hamster) and I were alone. Don’t get me wrong, he keeps me busy. He is as naughty […]

Close

Close

[…] From ‘Grant Museum of Zoology’, May 20, 2013 […]