Where is the wild?

By Jack Ashby, on 12 May 2011

A delayed account of zoological fieldwork in Australia – Part 15

For the past 14 weeks I’ve been writing the account of the five months I spent on ecological fieldwork in Outback Australia. This is the final post for that trip. I visited many of the world’s major ecosystem types – rainforest and desert, alpine and coral reef, moorland and woodland, heath and kelp forest, monsoonal woodland and swamp. I trapped, tracked, handled, spot-lit, sampled and photographed some of my most favourite animals. Not wanting to boast, but I had a frankly awesome time.

A few weeks back I wrote about what makes an animal wild. To finish this series I’d like to ask a similar question of the landscape. Over the course of those five months I barely went inside, or even saw a building for that matter. Sleeping in a tent, cooking on a fire, drinking from a stream and washing in a bucket certainly should make you feel like you’re living relatively wild. At least with respect to my London life.

I know it’s a cliche, but even after weeks at a time of living like this, uninterrupted by people, electricity and phones, something generally would pop up and remind me that people have been here before and massively affected the land I was living on. There were instances when I did feel the isolation that should come with a lack of humanity, and I’ll get to those, but for much of the time although the distance in kilometres or decades to the nearest set of people was massive, the effects of far off neighbours or previous visitors made it feel much closer.

I have written a great deal in these posts about the presence and effects of feral animals in Australia, and so I wont go on at length here. There was barely a day when I didn’t encounter a feral pig, buffalo, starling, camel, toad, fox, cat, sparrow, rabbit, pigeon, myna, dog, cow, horse or deer. One morning I remember boiling billabong water on the fire as dawn was breaking in the monsoonal forests of the Arnhem Land Plateau. This time, before anyone else in the team got up, was often an a chance to sit back and bask in the wild, remote peace. On this occasion, however, a feral donkey began to charge, screaming and eeyoring. After the initial shock and then hysterical laughter, I charged back and he backed off. However it somewhat ruined the mood. I’ve seen plenty of Asiatic wild ass in India, but donkeys have something ridiculous about them that’s absent from their “natural” relatives. Donkeys are just too reminiscent of the people that brought them here. Instantly I was reminded that this land had been settled and farmed; no longer natural.

Australia’s ecosystems have been massively changed by the people that have visited, starting with the first aboriginal settlers over 50,000 years ago. Their activities changed the fire regime of the continent, and with it the climates, plants and animals. Among other things, there were once massive marsupials filling roles occupied elsewhere by elephants, lions and tapirs. Obviously this information isn’t something you can readily see in the bush – you have to have known it already. But in knowing it, even when waste deep in a spring miles from anywhere, as wombats amble nearby, you know that the land you are in isn’t the way it should be.

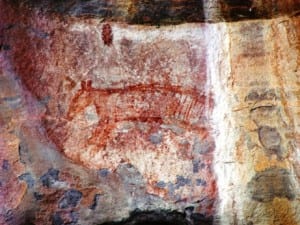

I am a massive fan of the thylacine. This stripy wolf-like marsupial officially went extinct in 1936 (though there have been thousands of unofficial sightings since), when the last captive individual died in Tasmania. Tasmania had been their refuge since their mainland extinction a couple of thousand years before. I could barely contain myself when I was taken to this aboriginal rock art depicting a thylacine in the Northern Territory – a palpable reminder of the predator’s existence there, and how different the regions ecology is now.

There were places and times when it really did feel wild. Tasmania’s central highlands was good for that, or watching the sun rise over the world’s largest parallel dune system in the Simpson Desert. Normally I relish the emotions these situations create, but I did have one negative encounter with the wild I want to share. One afternoon in Arnhem Land we had time to spare between the dawn and dusk trap checks, so another guy and I decided to follow a creek up from camp and find its source. Just a couple of hundred metres upstream we found a big rock platform which the creek curved around. Rocky outcrops covered in wallaby and echidna poo stuck out from one side.

From this outcrop we could see another one a couple of hundred metres away, and we crossed over to it, and then across two more. At the furthest outcrop I thought it was big enough to support rock-wallabies, but no mammals showed up and we turned around.

In my head I knew the route we had taken turned right off the big platform, and then straight out, parallel with our original course, so I thought I knew the way back.

After ten minutes, however, we found ourselves in undulating scorched bare, burnt woodland. We had not crossed this land before and we couldn’t see the outcrops we had crossed. We realised we were lost.

Both of us realised what trouble we could be in. It was the hottest part of a hot day on open ground, we had brought no water, hadn’t told anyone where we were heading and wouldn’t be considered missing for hours. My heart rate rocketed while we tried to think what to do.

First, we went right towards rocks, as I knew we had turned right on the way out. It was not correct. We tried shouting – a desperate response. We couldn’t be far – not much more than a kilometre, but the others were probably by the noisy creek and out of earshot. I got quite worried and lost confidence in my recollections of our original route.

After several unsuccessful sorties, each time returning to same spot, we decided to try and head to where we first turned back and reassess. En route we heard water flowing, and decided to follow a dry stream bed, hoping it led to the same creek we had started at. Instead, and very luckily, we appeared on the first rock platform. It wasn’t what we were expecting, but was such a massive relief we couldn’t stop giggling.

When we had first realised we were lost we can’t have been more than 100m from here. What we did was foolish – we had originally set out to follow the creek, but changed plans when we saw the country. The country felt pretty wild that day.

Close

Close