Eye of Ox, Wing of Bat, Leg of Frog… Working in a Witches’ Pantry.

By Mark Carnall, on 24 January 2011

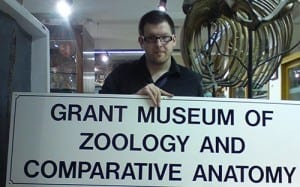

Working as the curator* in a natural history museum is a weird and wonderful job and one that solicits baffled stares at social events. A frequently asked question is, “So what does a natural history curator do?”.It is a good question and one that unfortunately doesn’t have a discreet satisfactory answer. The best way to answer it is perhaps via the medium of a (sometimes-depending on your browser Matt brown-) bulleted list.

Working as the curator* in a natural history museum is a weird and wonderful job and one that solicits baffled stares at social events. A frequently asked question is, “So what does a natural history curator do?”.It is a good question and one that unfortunately doesn’t have a discreet satisfactory answer. The best way to answer it is perhaps via the medium of a (sometimes-depending on your browser Matt brown-) bulleted list.

What Does a Natural History Curator Do?

- Detective Work. Finding a reliable estimate of how many species of things there are is impossible (see here for more information). Many fossil species remain unpreserved or undiscovered and many extant species of thing are yet to be described. Fortunately, working in a museum that specialises in zoology significantly increases the chances that one will be able to identify any given specimen. Still, the chances of identifying any animal specimen in the museum could be anything between 1 in 3 million to 1 in 30 million. There’s always a chance it could be a completely new species. Fortunately, experience and expertise helps to narrow down the search. Are you looking at a specimen with a bony skeleton? That narrows the search down to around 60,000 described species. Is your animal hairy? Well then, it’s probably one of 5,000 or so mammals. However, the chances are that you won’t have an entire animal in front of you to identify. It might be a single bone or in the case of microscope slide preparations a section of a single organelle.

- Historian. Interpreting evidence is a very Important part of curating an historical collection. For zoological specimens all the information we have about a specimen pre-mortem increases the potential scientific value of a specimen and what is can tell us about the biosphere. Many of our specimens are accompanied by labels, inscriptions, catalogues and occasionally notebooks and publications but do we trust this information? Who wrote this information? Was it the world’s leading authority on the animal in question or was it an educated guess from a work experience student? Is the available information primary evidence or was it retrospectively deduced, a common practice in natural history? Was it information from last year or information from 1830?

- A Science Communicator. Typically, visitors to the Grant Museum often have a lot of questions about the natural world and we pride ourselves in ensuring that at least one of our zoological team is on hand to answer any questions are visitors may have, typically, then pulling specimens out of cases and drawers to show people key features. However, we don’t know all of the answers and dealing with visitor enquiries can be one of the most satisfying aspects of the jobs. At other times as museum workers we represent the ‘frontline’ of science and in the past I’ve had to deal with visitors who have a lot of confusion with ideas around evolution, physiology and Earth history. Not only is this kind of work engaging but also it really helps to ground the way we fundamentally work in the museum. Are we seeking to engage natural history geeks only? Or do we hope to enlighten a visitor with no knowledge base at all? Or do we try to please both? Or neither, isn’t that being extraordinarily authoritative, elitist and arrogant? Then again, sticking a bunch of specimens out on display without raising tricky issues is another form of unethical practice (even if visitors would enjoy themselves regardless).

- A General Dogsbody. This post could easily turn into an epic thesis so for the sake of brevity here’s a small selection of other things a natural history curator may be required to be: public speaker, politician, bar person, researcher, projectionist, artist, conservator, manual labourer, advocate, consultant, mediator, author, glorified porter, lecturer, television presenter, talking head, tour guide, administrator, manager, coroner and even a stand-up comedian.

This post is just a taster of the sometimes odd life of a natural history curator and this blog will over time give even more insight into life a the Grant Museum as well as life in various other museums and collections at UCL.

*See this interesting article about the disambiguation around the title ‘curator’ Visual Thesaurus (via Prerogative of Harlots).

UPDATE 4th February to investigate apparently bulletless bulleted list.

2 Responses to “Eye of Ox, Wing of Bat, Leg of Frog… Working in a Witches’ Pantry.”

- 1

-

2

alan wrote on 30 July 2014:

“Typically, visitors to the Grant Museum often have a lot of questions about the natural world”

I’ve been working in museum since about 10 years and believe me: you will never predict what visitor want to know.

Close

Close

You forgot “washer-up.” Though I suppose you could stretch bartender to include the morning after.