Land, Building Supplies and Repair-People: Differing Visions of Urban Futures in Ulaanbaatar

By ucsarpl, on 8 February 2016

This is the fourth blog post in a series about debt and loans.

As part of our series on debt, this post discusses some emerging subjects appearing in a context where there is a severe lack of cash flow. It describes a section of Mongolia’s construction industry where forms of indebtedness leave people surrounded by commodities (land, labour and building supplies) but unable to make money.

The Ulaanbaatar district of Zuun Ail, just north-east of the city core, has long been a place where one can buy building materials. The main street of Tsagdaagiin Gudamj that stretches northwards, is a crowded and bustling street lined with many shops and large centres housing sellers of all kinds of fixtures, paints, wood, and many other types of building supplies.

Mongolia’s period of intense economic growth during 2009-2012 saw a simultaneous boom in construction occurring throughout Ulaanbaatar. Since this time however, Mongolia has seen an equally rapid economic downturn, including a drastic reduction in foreign direct investment. Due to a number of factors, the construction sector has felt this overall economic slowdown harshly and there is currently a severe lack of cash flow in the industry. Bank loans often come with high interest rates, making it difficult to make a profit when buildings are completed (if enough financing is acquired to complete them at all). In the current economic climate, many major construction companies commonly operate through large-scale forms of bartering to acquire materials to finish projects. For example, a construction company can barter a $100,000USD jeep to obtain $100,000USD worth of concrete blocks.

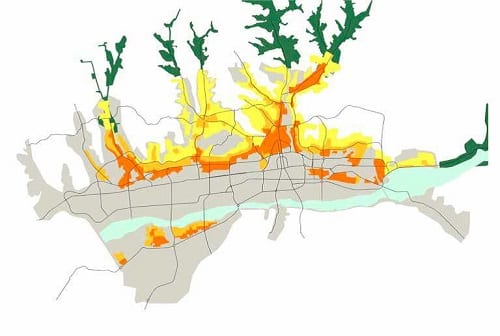

During this economic slowdown, fuelled by a government plan to redevelop areas of Ulaanbaatar’s sprawling ger areas with affordable apartment housing, land from several ger areas have been acquired by construction companies where some people choose to swap their land for either compensation or apartments. Due to some of these processes Zuun Ail has become a place were competing visions of urban futures have begun to materialise in sometimes conflicting and contrasting ways.

Spheres of Anticipation

In Zuun Ail, several areas of hashaa (fenced blocks of land usually containing a small house or ger (tent)) were signalled for redevelopment into apartment housing. However, due to the economic slowdown, several plans for construction have, as yet, failed to materialise. When I visited Zuun Ail in October and November 2015 some construction sites were lying dormant.

Image 1: Zuun ail redevelopment. An apartment complex lies half-built alongside many occupied hashaa.

Some land owners in the area preferred to hedge their bets. Instead of choosing to receive compensation from construction companies wanting to acquire their land, they preferred to sell the land privately, hoping to let their land increase in value so they can obtain a better deal at a later date. In this uncertain economic climate, for many the value of an apartment is viewed as more unstable and less reliable than the value of land beneath peoples’ feet. Attention shown by construction companies keen to acquire land for redevelopment can increase a land owner’s attachment to their land, where land is viewed as the main value-holder.

Image 2: A hashaa owner advertises their land for sale hoping for a better deal, while construction work has been completed around them.

Additionally, along the perimeter of Zuun Ail, several key infrastructures – sewerage pipes and underground electrical cables – were in the process of being laid through funding sourced by the Ulaanbaatar municipality. These key infrastructures are severely lacking in the ger areas of Ulaanbaatar overall. These infrastructures were designated for future apartment buildings in areas further away from the city core and wouldn’t be available to nearby hashaa residents per se. However, some residents of these blocks of land anticipated that the close presence of such infrastructures would only increase the value of their land.

Image 3: Sewerage systems are laid down in late October 2015, the installation cutting through a person’s hashaa.

The Zasvarchin (repair-person)

Within the ebb and flow of anticipation and stalling wrought by construction companies and the installation of infrastructure in the larger areas of Zuun Ail, sit a number of people who are deeply affected by the fluctuations occurring in the construction industry. These people could be considered emblematic of some of the emerging subjects arising out of Mongolia’s rapid economic change. Motivated by a desire to better understand the construction material supply areas of Zuun Ail, I went one cold afternoon to visit some of the construction material vendor centres (barilgyn material hudaldaany töv) that run through the main street in this district.

It was a cold day, grey clouds hung low in the sky and there was a bitterly cold wind. I felt the cold start to bite into my clothing and limbs the longer I stayed outside. This was in the middle of November, never a flourishing time for Mongolia’s construction activity in the best of economic circumstances. However, I was curious about how sellers in this area perceived the current state of the industry given Mongolia’s economic downturn.

The main street was busy. It was lined with stores and vendors selling all sorts of construction and building materials, from windows to wooden beams and pipes. The street was littered with signs directing customers to stores off the street. There were many cars and a lot of people weaving through traffic and on the footpath – people coming and going buying this or that small goods for some construction or hardware project or another. Small pick-up trucks waited with the sign ‘achaa awna’ in the window – you can rent them to transport your materials. Overall, on the surface it seemed that this area was where people bought items for small-scale projects, or for supplies for completing the interior of buildings. I came across a hudaldaany töv (sellers centre). It had a number of concrete steps reaching steeply up to a large two story building.

Image 5: Various advertisements on the steps leading up to a construction materials market. Some are advertising sales.

On the steps were some older and middle aged people milling around, each standing on their own. Quite a few of them men. On a little roadway that services the front entrance stood a stocky security guard. She wandered slowly in this space not looking at anyone in particular, but often faced the front of the building standing away from the main road. In this small, dispersed crowd on the steps an older man and a woman several years younger than him carried small signs around their necks displayed on their chests. These were people available for hire to do small handy-work, interior construction tasks – painting and decorating, installing kitchen cabinets or fixing the interiors of apartments. They stood in the cold waiting for someone to hire them. They were all silent, standing a few feet away from each other gazing solemnly out towards the road.

I decided to see what was taking place inside the building. It was crowded at the entrance, with people milling around organising packages in their arms before leaving. Once inside, I turned left and immediately saw two women in front of us with similar signs around their necks. The women would have been roughly in their mid-fifties. They were both looking for work. The signs around their necks explained they were available to do painting and interior decorating. I introduced myself to them and asked how they were, how work was going and how the year had been. They said that that work had been extremely bad, that they were lucky to get work every 14-15 days or so. One lady commented that it was common for such itinerant workers to be from the countryside, and that they often head back home after the construction season ends. The two of them, she said, were doing this work to support their children, that private construction companies only pay very low salaries. She personally lives in Zuun Ail and a lot of her relatives do the same work that she does. These people, I learnt, are described as ‘zasvarchin’ – ‘repair person’ or handyman.

Later, upon leaving this centre (which I will describe further below), we saw that a woman standing on the front steps was possibly being hired. A man arrived with a toolbox and was discussing something with her. I was told that it is a common way for people to be hired in this industry. To the left of the entrance, a series of workbags were hung up on some grates covering a window. As we left, the older man in his late fifties or early sixties was still waiting in the cold with a sign around his neck.

The Materiality of Debt

Going into the centre, I saw several rows of closely packed stalls lined with goods from floor to ceiling. Some vendors were selling linoleum and other kinds of flooring, while others were catered for lighting. Others sold all sorts of safety equipment and others still were selling anything from brooms to nails or rope and hardhats. There were several stalls with people sitting alone unattended by customers.

Two men in one corner of the store were playing cards. At first I just assumed that these sellers simply had more free time during the slow-down of the industry in mid-November as winter approaches. However, as my day progressed, I noticed more and more card-games, which prompted my thinking about the current levels of business for these sellers, the state of Mongolia’s construction industry, and some of the financial positions these vendors are in.

I stopped to talk to people for a few minutes each time as I walked around. Introducing myself and my research, I asked everyone generally the same questions – how has the year been for their business, if bad, when did it start, what do they think it will be like later, do they allow barter. At the first stall I visited, a stall of mixed supplies, from nails to tape measures, to rope, the vendor said business this year had been bad, muu, and that it started getting bad around spring of 2015. She said that the industry won’t start up again until after the winter, not until May 2016.

I went upstairs to a floor that was much quieter. On this floor were a lot more stalls that were direct supply outlets for companies selling only one or two items. I found a woman texting on her phone in a stall selling bathroom sinks as well as long, thin, green pipes used for supplying drinking water. Happy to talk but without looking up much from her phone, she too said that since spring 2015 business had become pretty bad. I asked about whether they barter as a form of transaction. She said that people come in and propose bartering arrangements and that it is possible to do so. She said that the supply company she works for is also happy to barter sales items in lieu of rent money to keep hiring this shop space, but that it hadn’t yet come to that.

Walking along this floor, several shop spaces were left vacant. I waited outside a store that sold power tools. This store had several customers and also sold quite high end brand equipment of saws, drills and several other specialised power tool equipment. I thought that maybe she might have had better business, or at least engage with more instances of bartering, given the high prices of her goods. This vendor said that since August 2015 business has become really bad. She said that a few people try to offer a proposal (sanal) to barter an item in exchange for power tools, but that she refuses to do so. She said that some people offer to give her an apartment in exchange for goods, but that because the apartment price is very low, she doesn’t want to do it.

On this dimly lit floor towards the back of the building, there was one store that had a table in it selling electrical fittings. A lot of the other stalls containing goods were open but unmanned and the hallways were empty of customers. In the electrical fittings store, away from the gaze of customers walking up the stairs, there were several people playing a big card game amongst each other. Leaving to go back outside, I walked along the street to a similar sized hudaldaany töv. Walking along similar rows of light shops and multipurpose electrical stores I saw another card game taking place between two vendors who were gambling money on the outcome.

I began wondering at this point that perhaps these middle-sellers, located in a larger supply chain of building materials, would have a very limited ability to barter. People hired by suppliers as sales clerks to sell their goods would probably need to provide to their employers cash for the items sold. Any decision of bartering would have to be made by the company, not them. Similarly however, if they are working for themselves they would need to receive cash in order to purchase future sales items or, most likely, pay off loans. They were surrounded in suspense by a packed stall of goods lining the wall from top to bottom, but with an absence of customers. These goods formed unmovable, material representations of someone’s financial debt, where the unseen money is stuck in these objects that cannot be sold. These vendors are caught in a position of requiring cash in an increasingly cashless environment and lack the leverage to make bartering properly profitable for themselves.

I went to one more hudaldaany töv that day. This one had all kinds of supplier stores often adorned with brand named signs and often selling singular items. There was one store selling fire hydrants and another store sold speciality bathroom fixtures. In one store there was a poster stuck on the wall displaying a picture of piles of American dollar bills with the words “First Billion” written in a big heading at the top – an attempt to causally evoke future wealth and fortune.

Image 6: Inactive spaces – A shop space formerly selling toilet fixtures lies vacant and open for rent.

Going upstairs to the second floor of this building, there were several store sites left vacant with the words “for rent” on the door. Walking along this corridor I found the manager of the building sitting in their office and was able to speak to them for a few minutes. They informed me that some distributors have two or three shops and that lately they have often been combining them into one, as they can’t make a profit with multiple stores. The manager said that the hired sales assistants working in the additional stores lost their jobs and that sales overall have been decreasing since 2013. The big companies setting up the small shops can’t pay salaries and rents on all of them. Only seasoned veterans, this person explained, with established older businesses can do this sales-work, not newcomers. In this climate of debt and an inability to secure cash, new businesses do not thrive and quickly close.

As I walked out I found another sign saying “for rent” on an empty shop space, and went to take a photo. However, I quickly realised that behind shadowed glass was a whole vacant shop space full of men engaged in another big card game. I left to go down the stairs. Following the number of card games during this day in the several hudaldaany töv gives an example of action, of sociality that has arisen out of a lack of business activity. It also reveals the social connections between these vendors that inhabit these sale spaces, people who are also in competition with each other. How much of this slowness is due to the bad state of the industry? Or how much is due to the fact that it was November and too cold for the construction industry to be booming at this time? Considering peoples accounts of the state of their business, perhaps it is both.[i]

All photos © Rebekah Plueckhahn.

[i] I would like to thank G. Delgermaa for helping me source information and Doljinsuren for assisting me with this research.

Close

Close