“Shakhaanii Business”: Shared Debt, Privatization of Profit, and (Re-)Emergent Corruption Discourses in Mongolia

By uczipm0, on 2 March 2017

By Marissa J. Smith

Marissa J. Smith obtained her PhD from Princeton University’s department of anthropology in 2015, after defending a dissertation about Erdenet and its position in local, national, regional, and international contexts. She currently teaches at De Anza College in Cupertino, California.

With presidential elections on the horizon, as the Parliament called its fall session into recess and Mongolians began preparations for the Lunar New Year, Tsagaan Sar, major developments materialized regarding two particular issues that since the June 2016 parliamentary elections have become foci of interrelated concerns, controversies, and conspiracy formation about national debt, national development, and international mining projects, long noted and discussed on this blog.

The two issues are: 1.) the Parliament’s vote on February 10 that the state take (törönd avakh) the forty-nine percent share of the Erdenet Mining Corporation, deeming illegal the controversial sale of the shares on the and 2.) the announcement on February 19 of a “staff-level” agreement worked out with the IMF, $440 million dollars through a three-year “Extended Fund Facility” program. This announcement included that around five and a half billion dollars of “support” from China, Japan, South Korea, the Asian Development Bank, and the World Bank were also expected. China confirmed the extension of an over two billion dollar currency swap on February 21 during the diplomatic visit of Foreign Minister Ts. Munkh-Orgil, while Erdenet was not officially addressed during Munkh-Orgil’s visit to Russia on February 13-14.

As noted and discussed on this blog, the senses prior to and just after the summer elections were of slow-down, “stalling,” “resisting closure;” the feeling may now be characterized as of urgency, sped up, as the first of a billion dollars’ worth of loan payments come due this year and presidential elections approach. With $580 million due for maturing bonds in March, the announcement of the IMF decision has been met with some relief. However, this relief has also been mixed with suspicions and speculations like those around the highly controversial “matter of the Erdenet 49%.” Some have also tied the two together:

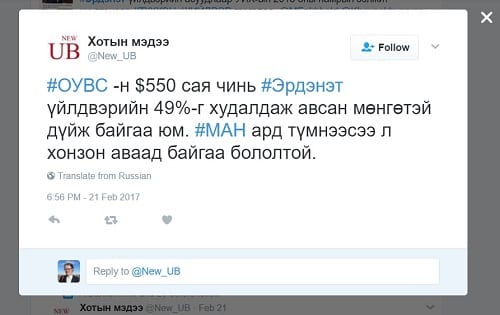

“The $550 [sic] million of the IMF matches the amount of money that the 49% of the Erdenet enterprise was purchased for. It seems that the Mongolian People’s Party (MAN) is “settling accounts” of/with the people.”

Both of these events are easily placed in narratives noted and discussed in this blog. With the IMF package, there are ever more loans than can be paid off, as more loans are taken to pay for loans. While much more on the IMF package and associated “projects” from the ADB, World Bank, Japan, and South Korea can be expected after Tsagaan Sar, for now the announcement of stagnant salaries and increased taxes associated with the IMF’s conditions for the loans has been at the center of concern. The major worry with the Erdenet 49% is that shares (khuv) have been, and will continue to be, wrongly distributed. As I have written about elsewhere, while international headlines described the action as “nationalization,” what is expected is a re-privatization, one that will favor a small group of politicians, working together across party lines (see Bumochir Dulam’s post on Mongolia’s deficit of institutionalized and regulated opposition politics) and foreigners (with some of the major politicians accused hailing from minority ethnicities subject to being questioned as to their degree of “Mongolness,” like many of the residents and employees of Erdenet itself).

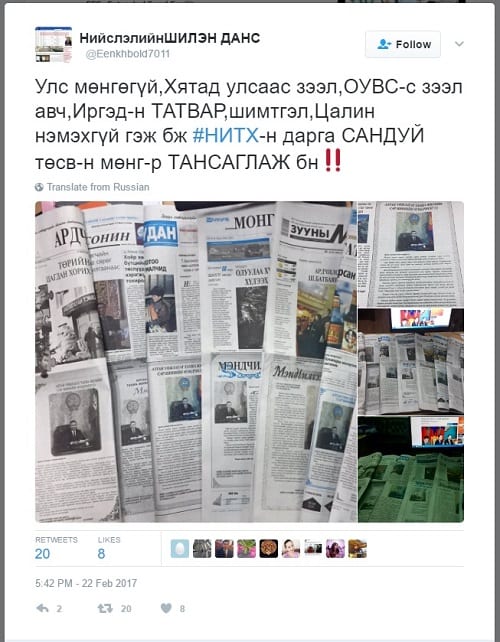

“The country has no money, has taken loans from the IMF and China, there will be taxes and fees on the citizens, salaries will not increase, they say. The Ulaanbaatar City Council head SANDUI LIVES IN LUXURY on budget money!!”

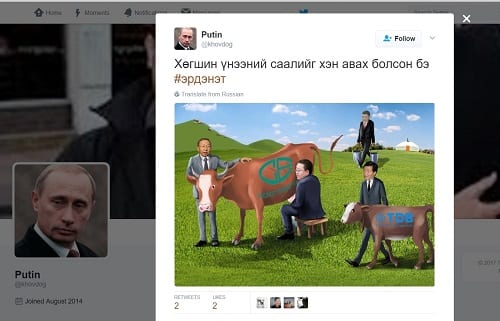

Members of MANAN milking Erdenet, the “exhausted cow.”

How are these two issues connected? The IMF cites predictions of a return to eight percent growth in the national economy by 2019, but why is the premise that privatization will generate excess wealth to pay off loans unbelievable and genuinely questionable, from the perspective of Mongolian citizens as well as an anthropological perspective?

Who Owns the Shares?

Beginning a period of field research this past summer, I arrived in Mongolia just one day before the Parliamentary elections. After settling in my hostel, I glanced at twitter and saw something about Erdenet trending (before now, highly unusual), but with arrival errands I was unable to look into the matter beyond noting a connection with the discourses about “offshore” assets that had broken into Mongolian political commentary in spring 2016 with the release of the “Panama papers.” The night of elections, I attended a party with other foreign researchers and journalists, where I was told that Prime Minister Ch. Saikhanbileg had made his announcement that Erdenet was now “100% Mongolian.”

Returning to twitter to take a closer look, I found that this very notion of Erdenet having become “100% Mongolian” was a major point being refuted in the tweets I had been seeing. In conversations considering the election results, consensus quickly emerged that the timing and grandiosity of the announcement had been a key element in the Mongolian People’s Party’s taking eighty-five percent of the Parliament, the announcement backfiring badly for Saikhanbileg and his Democratic Party. As I spoke with Mongolian friends with varying degrees of relation to Erdenet and the Erdenet Mining Enterprise, the theme of “who has taken the 49%?” continued to dominate conversations. Everyone, not only Erdenetchuud, the people of Erdenet, felt dispossessed. The matter did also come into my arrival errands, as while I waited to have a notarized copy of my passport made near the Government Building the morning after the election, the notary held court with clients on the issue of who had the 49%.

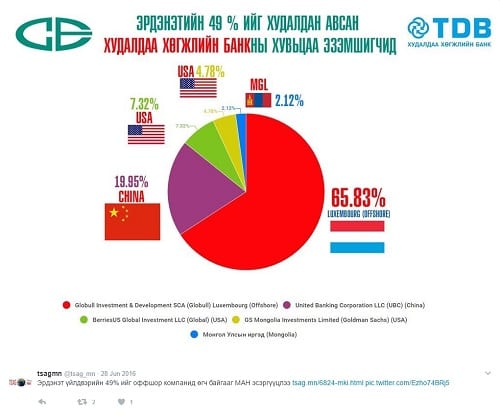

Answers to this question ranged widely: an eye-catching tweet showed a pie chart with the percentages of the Trade and Development Bank owned by shareholders in China, Luxembourg, United States, and Mongolia (just over two percent); those in and close to Erdenet tended to allege that the 49% had gone or would go into Chinese hands; others focused on individual politicians, doing politics in the way noted by Rebecca Empson: “speculation and circulation of rumours, of factions, motivations, alliances and actions of individuals dominates political talk.” A friend who had worked at Erdenet while I conducted dissertation research there and was now living in Ulaanbaatar also framed things in this way a few days after the election, listing everything that had gone downhill since changes in political appointments following the 2012 elections. Her relatives had been compelled to retire, access to the sport center had been restricted with entrance fees, and there was speculation a national-level politician would take the vacation resort. She also told me how she was one of the few regular salary-earners in her extended family and was helping to pay off the mortgage on an apartment in the name of a family member while living in another apartment owned by still another family member, caught in an arrangement that reminded me of the story in the post by Bumochir Dulam.

The shared nature of debt makes privatization excessively threatening, go beyond expropriation, in ways that make scalar and even erase distinctions between consumer, corporate, and national debts. If wealth, and the relations generating wealth, are distributed into closed groups or exit from the national community, the burden of debt (made heavier with increased taxes and stagnant and evaporating wages) remains widely shared with less possibility of being alleviated. A pattern has even emerged in which it at least appears that more and more debt is taken on as shared, while ownership and possession of capital and profits is made increasingly exclusive. If the knowledge of where this ownership and possession lies and moves is unavailable, its realm of exchange cannot be entered, and thus “transparency” (shilen dans) has become a cornerstone of President Elbegdorj’s policy without stemming the flow of suspicion and speculation over conspiracies involving members of the government and business elite.

As posts on this blog from over the past year articulate, the mirroring of debt in personal life and one’s own business and household on the one hand and at the level of the national economy and international relations on the other are not merely apparent. As Lauren Bonilla put it last February, the “external debt” is also “internal debt” – for individual Mongolian citizens this debt is their own, and also for members of government who have calculated the share of the debt as held by every citizen (including pensioners and children). Most lately, at the end of January, as Mongolians were awaiting news on the IMF agreement and the Erdenet matter was being investigated in Parliament, major English news outlets reported that, “oddly enough,” Mongolian citizens were offering their own cash, jewelry, and livestock towards paying off the national debt. (This phenomenon and associated negative international attention were also mentioned by President Ts. Elbegdorj in his address to the Parliament before the vote on taking the 49%, which I assume is connected with the apparent encouragement of the practice by Prime Minister J. Erdenebat, though it has been stated that the donations, khandiv, will go into a separate fund and not be put towards debt payments. Both moves seem to demonstrate that the government members seek to take responsibility and authority for paying the debt onto themselves.) Bumochir Dulam also shows how the “8%” mortgage program tied not just individuals to the state bank, but also groups of friends and family, being at least informed by employees of commercial and state banks. The concerns of the Mongolian economists he cites as to who actually benefitted from the program and attendant negative effects on the economy broadly are apparently also borne by the IMF, who support legal reforms of the mortgage program and regulation of the state bank, passed at the end of the fall session of Parliament.

What is “shakhaanii biznes”?

On being told of the sale of the 49% on the election night in June, my reaction was of disbelief; having studied Erdenet for almost a decade I thought of the central roles I have seen the enterprise and city hold in relations not only between Russians and Mongolians (let alone other international relationships), but also among Mongolians; the great stresses that would be required to break these relations, the force with which these stresses would be resisted, and the massive scale of the potential fallout for the national economy and international relations, in which were also implicated the jobs and workplace communities of many of my friends, the infrastructure of the city of Erdenet, and the many Mongolians who accessed trade, schooling, healthcare, and employment more indirectly through association with the enterprise and its associated institutions throughout the city.

In the last two months, as I have followed news, opinion writing, and social media during the course of investigations by the Standing Committee on Law of the Ikh Khural, I have noticed a category for a particular kind of corruption that I had not picked up on before. The term shakhaanii biznes, or simply shakhaa, appeared particularly in connection with discussions of apparent conflicts of interest involving politicians most centrally involved with the movement to take the 49%. The term struck me not only as a category of corruption accusation I had been unfamiliar with, but also due to the force of its possible valences; a possible translation is “pressured” or “forced business,” but a related or homonymic verb with the meaning “to shoot” is commonly used in Mongolian as a strong swear word, analogous to English’s “f-word.”

While this concept and its contexts bear more investigation, the situation being described here is apparently that of trade being kept within a closed circle of participants to the detriment of those outside – as well as inside? The term might also refer to the “pressure” upon those inside to participate in the activity. In December and January the Buryatia, Kalmykia, and Mongolia-focused Russian-language news outlet asiarussia.ru ran two pieces (here and here) related to the issue of Erdenet’s 49% with shakaanii biznes in the headlines and with suggested translations, including tenevoi biznes (“business in the shadows”). Sociologist Alena V. Ledeneva, a major contributor to academic discussions about “barter economies” and “corruption” in postsocialist economies, devotes a chapter of her How Russia Really Works to tenevoi biznes, describing the way that networks of barter, in which the many participants she interviewed expressed being compelled to participate, kept the Russian economy itself, as well as individual Soviet enterprises (similar to Erdenet) going through the 1990s and beyond.

As I re-read Rebecca Empson and Lars Højer’s separate work about Mongolian pawnshops (lombard), it strikes me how it is not sharing or transferring property or personal substance itself that is objectionable, but being compelled to do so in conditions of anonymity or uncertainty, as the effects of these movements are so wide-ranging, potentially infinitely so. Such transactions involve and constitute ongoing relations, in which consequences and risk, as well as benefits and potential benefits, are shared. As Rebecca Empson shows, these “chains of debt” extend well beyond the lombard and the person handing over property in exchange for a loan, as she observed, remarkably, that a debtor had to also provide a list of telephone numbers belonging to other people also “accountable for payment.” The lombards themselves, Empson notes, are also “just ticking over;” rather than being profit-making ventures as her interlocutors alleged, they were as bound in chains of debt as their “clients.” Debt relations are not between a debtor and a creditor, but form “networks” and “webs” in which these distinctions become perspectival.

It seems that large enterprises and national economies and their politics are not so different, and thus are really involved and implicated in much more small-scale seeming interactions after all. To analyze Mongolian economy and politics, we must not lose sight of these points as we encounter one particular corruption accusation or conspiracy theory after another.

Close

Close