Scientist in Residence

Slade Scientist in Residence 2023 -24: Professor Duncan Greig

I’m delighted and honoured to be the sixth Slade Scientist in Residence. I’m a professor of genetics in the Centre for Life’s Origins and Evolution (CLOE). My main research method is experimental evolution: I observe populations of living organisms as they evolve, in my lab. We usually think of evolution as a slow process, but because microbes can reproduce very quickly, making large populations, they can evolve significantly in just a few days. I mostly use yeast, the same organism that makes bread and wine, because it’s easy to engineer their genes. So I can control the genetic starting point to test whether evolution proceeds in the way that theory predicts.

I’m delighted and honoured to be the sixth Slade Scientist in Residence. I’m a professor of genetics in the Centre for Life’s Origins and Evolution (CLOE). My main research method is experimental evolution: I observe populations of living organisms as they evolve, in my lab. We usually think of evolution as a slow process, but because microbes can reproduce very quickly, making large populations, they can evolve significantly in just a few days. I mostly use yeast, the same organism that makes bread and wine, because it’s easy to engineer their genes. So I can control the genetic starting point to test whether evolution proceeds in the way that theory predicts.

Isn’t it amazing that all living things on earth evolved from a single ancient ancestor? This is thrilling: it means that evolutionary genetics is like a time machine. All genomes today contain traces of the lives our distant ancestors lived, stretching back countless generations, beyond a billion years! But although we understand the process of evolution—mutations occur randomly and spread by genetic drift or under natural selection—predicting the outcome of evolution is difficult because chance plays such a huge role. If we could restart life all over again, or if we could observe it evolving on another planet, how similar or different would it become? Would the newly evolving species look familiar to us, for the same reason that dolphins and fish independently evolved similar shapes? Or would we even get species at all? It’s not actually obvious why we have different species. Why not instead evolve a single species that can inhabit a whole planet, or alternatively have near-infinite species, where every living individual is itself a single uniquely adapted species?

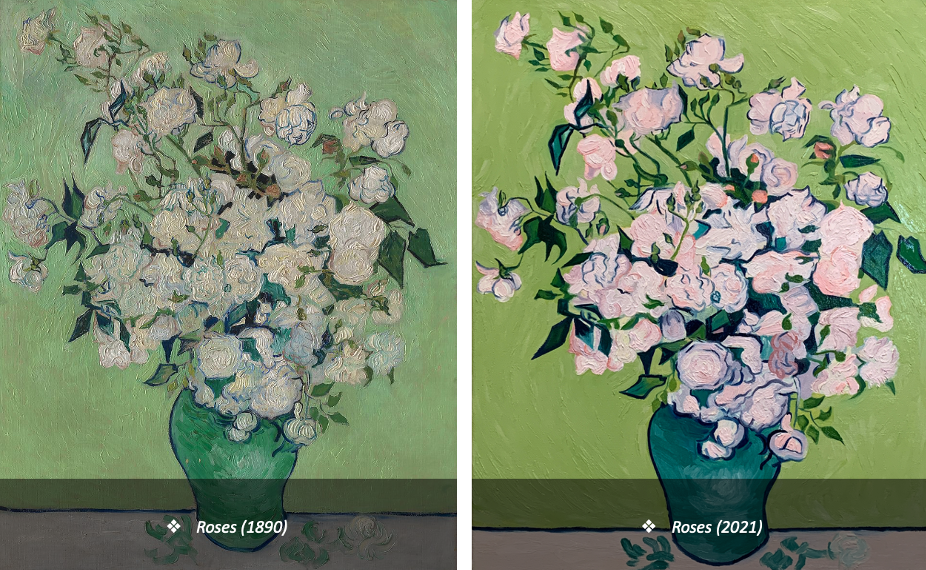

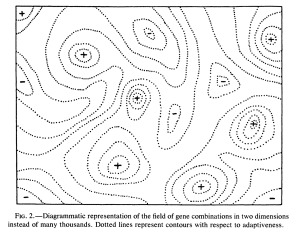

Example of an adaptive landscape, from Wright S (1988) Surfaces of selective value revisited. Am Nat 131(1):115–123

There’s a lot of scientific theory addressing these big questions. My research method is to test these evolutionary theories with laboratory experiments. For example, one way to define species is as groups whose members can breed together, exchanging and sharing similar genes, but not with members of other groups, who therefore evolve different genes and diverge as distinct species. Some of my experiments have involved changing the genes involved in the production of sex cells or courtship or mating to allow different yeast species to breed together (yes, yeast cells have sex!), or to inhibit breeding between groups of the same yeast species, and then letting them evolve.

Links between evolutionary biology and art are perhaps less obvious than for other sciences, though I’d argue that all science is really a form of art. Scientists, like artists, endeavour to understand and interpret the world, and they portray and promote their point of view through their work. We try to show others how to see through our eyes. The practice of genetics is highly abstract, but it is rich with visual metaphors, such as the adaptive landscape, or the phylogenetic tree.

It is the artistic, creative, part of science that I most enjoy. Designing an experiment, working with my hands, presenting a satisfying result such as a graph. The best experiments are profoundly beautiful. I loved doing A-level art under my brilliant teacher, the ceramicist Neville Ferry, and I was proud when he told me I could make my living as a potter. Although I eventually decided to study science rather than apply to art school, I’ve always maintained my interest in art and I still make pots—and other things—quite regularly. I’m really enjoying hosting two talented Slade students in my research group, and this summer I organised an interdisciplinary workshop for a group of artists and biologists at a remote research station. Exploring the connections between our different practices and processes is very stimulating, and I’m convinced there are enormous benefits (both ways) to working together. I’m very grateful to have the opportunity to do much more of this in the coming year in my role as Scientist in Residence.

Slade Scientist in Residence 2022 -23: Kimberley Selvaggi

I am thrilled to be the next Scientist-in-Residence (SiR) at the Slade School of Fine Art, following my two-year residency as Conservator-in-Residence (CiR)(2020-22). I was originally trained as a fine artist and got my undergraduate degree in art history. I then pursued my graduate studies in conservation (MSc) at the Institute of Archaeology, UCL. During my studies here at UCL, I had the privilege of being placed in an internship at the Slade with Jo Volley, where I was able to further develop my knowledge and interest with artists’ materials in a more scientific and analytical way. This placement ultimately led to the creation of the CiR role by Dr. Dean Sully (former SiR and my degree coordinator for the MSc), which has created a direct link between the staff and students at the Institute of Archaeology and the Slade.

As a conservator, I have mainly sought to specialise in the preservation of objects and works of art with painted or decorated surfaces, which has been greatly inspired by my own practice as an artist. Much of my research into the preservation of decorative surfaces has been looking at the permanence of colour. Many artists and scientists know that paints, pigments, and dyes can be rather fugitive when exposed to light for prolonged periods of time. This is often why many colours fade as they age, or they may undergo a change in colour.

My dissertation work set out to look at the fading properties of fugitive nineteenth-century paints, particularly that of eosin lake pigments, otherwise known as geranium lake, and most famously used by Vincent van Gogh, among other Impressionist painters. Geranium lake (a brilliant red) has been known to fade quite rapidly when exposed to light, and in some instances, the colour has deteriorated entirely from painted surfaces in as little as twenty years. I reconstructed this fugitive pigment and made it into a paint using nineteenth-century recipes (along with the expertise given by Dr. Ruth Siddall). My samples were put through artificial, accelerated ageing techniques where I was able to mimic and observe the colour fading to facilitate the creation of a reproduction of Roses (1890), a painting by van Gogh, which has notoriously suffered from the deterioration of this pigment. In terms of gaining a sense of van Gogh’s original conception, the fugacity of this pigment makes it especially challenging for the viewer. Therefore, my reproduction looks to imitate the act of representation through the study and analysis of material practice and give the viewer a sense of the original colour composition that has been lost to time. The practice of maintaining pictures through repainting, respectful of the images conveyed, is a standard method of conserving an image, and stems from a methodology that romanticises historic preservation.

This research has really inspired me to look further into traditional manufacturing techniques of paints and pigments along with other artists’ materials. I’ve recently been developing my interest in horticulture, and as Scientist-in-Residence, I hope to be able to push forward with the Pigment Farm, an initiative of the Materials Research Project, aimed at growing plants for cultivation of dyes to produce into pigments for artists’ use. I am excited for this opportunity to learn and develop new methods to experience the cultivation of colour, but more importantly to share this project and knowledge with the staff and students at the Slade.

Slade Scientist in Residence 2020 -21: Professor Daren Caruana

We are delighted to announce that Professor Daren Caruana, UCL Chemistry will be the 2021 Slade Scientist in Residence.

Statement From Professor Daren Caruana:

I am incredibly excited about this residency at the Slade School. Science has been my career but art has always been a firm passion of mine.

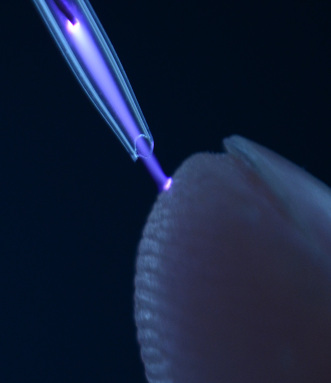

I originally identified as a biochemist and really enjoyed the interrogation of chemical systems within a biological setting. Over the course of my training, I was fortunate to have been exposed to the scientific process in several fields of research; eventually I landed as a physical chemist, or more specifically electrochemist. Electrochemistry is quite an important discipline that underpins many important technological applications, such as batteries and power sources, electroplating, sensing, and many more. My research focuses on ‘blue skies’ and less applied areas which often has no clear end use. Since I have been at UCL, I have been concerned with understanding gaseous plasmas, an area of research with is quite unique. The rationale behind this work is to investigate the properties of these fascinating electrically conducting gases, using an electrochemical approach. The presence of free electrons opens up the possibility of observing and possibly controlling very unusual chemical reactions. Electrons are normally discretely organised within atoms and molecules, however, if the conditions are favourable electrons tend to exchange between molecules or reorganise within molecules; this is the basis of almost all chemical change. In plasmas electrons exist freely in the gas phase and it turns out they can react in quite unique ways. So, I think of electrons as reagents or reactive chemical species rather than a consequential component of chemical change. Accidently, this work has led to the development of some useful technology which has resulted in a patent, centred on plasma jet materials synthesis. Of course, another benefit is the fact that these plasmas are beautiful to work with. There is something quite satisfying working with a hot ball of glowing gas!

|

|

| Butane flame with additives, photo credit: Matt Li | Argon plasma jet, photo credit: M. Emre Sener |

In the early stages of my career, I was a great fan of ‘Lateral thinking’, a way of thinking developed by Edward De Bono. Originally aimed at business and economic theory, it can be applied to many areas, and I would say that it shaped a lot of my research approach, particularly the way I think of ideas and exploring problems. The approach I adopt in my research is a lot of fun and very satisfying; although can sometimes lead into blind alleys; the difficulty is actually recognising this! I don’t often question the scientific approach, but it is probably about time I did. I am hoping this residency will give me the space to dissect my scientific approach and explore the parallels with the artistic approach.

Art has always been important in my life; I turn to oil painting whenever I have the time or life throws a pandemic. So, an opportunity to be involved with the Slade is an extraordinary opportunity for me personally. The shape of this residency will hopefully be symbiotic, a chance for me to study and learn, but if appropriate, contribute to various projects in the Slade. I look forward to step completely out of my comfort zone, be privileged for a chance to observe and appreciate the philosophy behind the creative process. With my chemistry hat on, I would like to explore how art practice uses chemistry and start to examine how the different facets of chemistry can play a role in the creative process or in the artwork itself. Although this residency will be for a short period, I hope to act a conduit between the Slade and the chemistry department for years to come.

Slade Scientist in Residence 2019 -20: Dr Dean Sully

We are delighted to announce that Dr Dean Sully, Associate Professor in Conservation, Institute of Archaeology, is this year’s Slade Scientist in Residence. He will be giving his first lunchtime lecture, “As a Scientist Resident in Insouciant Time” , Wednesday 16th October, Slade Gallery 1.10 -1.50pm.

Statement from Dr Dean Sully:

It is a great honour to become the 3rd Scientist in Residence at UCL Slade School of Art.

In my day job, I coordinate the MSc Conservation for Archaeology and Museums programme at the Institute of Archaeology, where I have been based for the past nineteen years. I hope that my term as Scientist in Residence will provide a direct bridge between the staff and students of the Institute of Archaeology and the Slade.

As a social scientist, I do have an ambivalent relationship with the authorising narratives of the scientific process that assume the role as the arbiter of truth about the reality of the world. The adaptation of scientific discourse is however used to justify the role of conservation within heritage institutions. This is a necessary, but insufficient foundation for effective heritage conservation.

Heritage was framed in twentieth century as the fear of losing the past, in a salvage paradigm that sought to gather together the vestiges of what was left in order to have some evidence of what was lost. In the twenty-first century, this is replaced by a fear of a lost future and a sense of the past as something to be ashamed of. The heritage paradigm becomes one of salvaging sufficient resources to sustain human population in a future broken world.

As a response, my conservation research seeks to address broad questions about how the world comes into being, beyond merely tautological justifications of fixing a past within the present. This engages with making heritage as a creative act in the present moment.

If scientific processes aim to explain how things are, then creative practice has the potential to explore how things should be. This speculation becomes a means of building a bridge between dominant narratives and less powerful stories that may lie hidden. By imagining alternative narratives, interactions and pasts, we are forced to speculate on other possible, plausible future worlds. If we speculate more about everything, reality may become more malleable and preferable futures more achievable.

In my own heritage work, I have benefited greatly from collaborations with creative practitioners. These exchanges offer the opportunity for heritage practitioners to look in on themselves, and for artists, to gaze across the boundaries of the heritage worlds that we create.

Rather than acting as a host for Artists-in-Residence, as Scientist in Residence, I now get the chance to be a guest in your creative processes. As a respectful guest, I hope to share my projects that engage creative practice in the process of heritage conservation. More importantly from you, I hope to learn new forms of future making that create space for playful experimentation and offer new approaches to the practice of making future heritage objects and places.

Associate Professor in Conservation

Coordinator for MSc Conservation for Archaeology and Museums

National Trust Conservation Advisor for Archaeological Artefacts and Collections

Coordinator for Centre for Critical Heritage Studies: Curating the City Research Cluster

Websites and social media

UCL Conservation Blog

UCL Conservation Facebook

Subscribe to Institute of Archaeology news and events on the UCL Archeology

As a Scientist Resident in Insouciant Time

Slade Gallery, Wednesday 16th October 2019, 1.10 -1.50pm

‘If I were a scientist asked to be in residence at the Slade School of Art, this is the sort of lecture that I would imagine I would present. I would be likely to include some introduction to my scientific discipline, and possibly how the interaction between creative processes and heritage practice provides the opportunity for challenging established ways of working. It would probably describe the planned visits, tutorials and seminars that I would expect to arrange between the Slade and The Institute of Archaeology. I would be fairly sure that it would identify several projects that I would hope to develop with staff and students at the Slade, including an exhibition with South London Gallery’s Art Assassins, Centre for Critical Heritage Studies’ Hidden Sites of Heritage, UCL Repair Café, and use of speculative design to produce an exhibition of Insouciant Objects from the Museum of Beyond. But, by stating it in this way, I am still uncertain if it is now more likely to be brought into reality than before’.

Dean will be available after the talk for informal chats and/or to make future appointments with either staff or students.

Slade Scientist in Residence 2018-2019: Dr Ruth Siddall

We are excited to announce that Dr. Ruth Siddall, Geologist and Pigment Analyst is this year’s Slade Scientist in Residence following on from last year’s very successful residency with David Dobson, Professor of Earth Materials, UCL. Ruth will be based in the Slade School of Fine Art for one year from this term and will be giving her inaugural lecture Arcadia Lost: Geologies and Art Histories of Classical Landscapes on Wednesday 24th October 1.10pm-1.50pm in the Slade Gallery. All welcome.

This residency has been born out of the Slade Materials Research Project and we are very grateful for support from Professor Anthony Smith, UCL Vice-Provost (Education & Student Affairs) and Professor David Price, UCL Vice Provost (Research) in making this innovative position possible.

Ruth says of her new role:

‘I am delighted to have the opportunity to be the 2nd Scientist in Residence at UCL Slade School of Fine Art.

My current job at UCL is Student Mediator, a role based in the Office of the Vice-Provost Education & Student Affairs. However, by qualification and experience I am a geologist with an interest in the application of the Earth Sciences to cultural heritage. My interests are in the evolution of archaeological landscapes and their mineral resources; stone, clay and pigments and their use in architecture, sculpture, ceramics and painting. Research-wise, I have mainly worked within Greek archaeological contexts but have also carried out research in Italy, Turkey, Egypt and the UK on Neolithic to Roman-period archaeological projects.

That scientific techniques could be used to further the understanding of art and architecture first became apparent to me when I began a research project at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens studying building materials in Ancient Corinth. This experience made me realise that there was not a single ‘past’ and that the geological environment in which folk lived influenced the choices made by artists and craftspeople over the materials they used and how these materials were valued. I began to realise the continuum between science and art/craft in the understanding of material remains and thus sparked a life-long interest in the science of art.

I also have a great interest in materiality and technology in contemporary fine art. This ranges from the experience of the landscape as art to specialist material-based collaborations with artists including Jo Volley, Gary Woodley, Onya McCausland and Amira Fritz at the Slade and Josh Bilton, Katrina Palmer and Thomas Appleton. I am a member of the Tracing Granite project coordinated by sculptor David Paton which is a cross-disciplinary exploration of the granite landscapes of Devon and Cornwall.

I am also a member of the Slade Material Research Group and have collaborated with Jo Volley, Gary Woodley and Malina Busch on The Pigment Timeline Project. The characterisation of historic pigments is a particular research interest and I am co-author of the book The Pigment Compendium. I am also proud to have contributed to a number of studies of materials used in architecture, painting and sculpture.

I am very much looking forward to working with staff and students at the Slade hoping to share knowledge, learn new skills and experience some opportunities for creativity!’

Slade Scientist in Residence: Prof David Dobson

UCL has announced the establishment of a new Scientist in Residence at the Slade. The first UCL Scientist in Residence will be David Dobson, Professor of Earth Materials in UCL’s Department of Earth Sciences. Professor Dobson will be based in the Slade School of Fine Art for one year from January 2017. This residency has been born out of the ongoing Materials Research Project.

Professor David Dobson’s first lecture, ‘Elephants in Stilettos: studies of the Deep-Earth’ took place in the Haldane Room on 11th January 2017 at 1pm.

Blue from Iron

David Dobson

The colour of most minerals arises from electronic charge transfer between transition metals – most commonly between iron in its tow valence states of 2+ (ferrous iron) and 3+ (ferric iron). In most minerals the iron is surrounded by 6 oxygens in octahedral coordination; this results in reds and yellows in ferric-dominated minerals and greens in ferrous-dominated minerals. If the iron ion ends up in tetrahedral coordination (only 4 oxygens surrounding it) then a blue colour is produced – this is the colour centre in Prussian blue – but this is very rare in natural silicate minerals because the normal tetrahedral sites are too small to take the ferric ion. Iron can be forced into tetrahedral coordination in silicates by pressure which compresses the ferric ion faster than the silicate ion.

High-pressure experiments have shown that several bright blue silicate minerals exist with ferric iron in tetrahedral coordination. At low pressures serpentine dehydrates into olivine, pyroxene and haematite, giving the mixture a rust-red colouration. Above 80,000 atmospheres pressure serpentine forms pyroxene plus ‘phase A’ which contains tetrahedral Fe3+ and is a rich royal blue colour. Olivine transforms into ringwoodite at pressures above 200,000 atmospheres with ferric iron sitting on the silicon site, charge balanced by a proton – again very rich blue. These minerals are no good as pigments as we can only synthesise them in milligram quantities and they are not stable under normal conditions.

It is possible to force iron into tetrahedral coordination at low pressures by replacing the silicon ion with a larger species; phosphorous and germanium are good candidates. Vivianite is a hydrated iron (2+) phosphate which is white when pure, but on exposure to air some of the ferrous iron oxidises to ferric iron, producing the blue colour found in blue earths. Synthetic vivianite starts off a very pale blue and takes several weeks to darken to its final colour. The zinc silicates and germanates are interesting candidate materials as all of the structural sites are in tetrahedral coordination so should produce blue-iron bearing compounds. Work is ongoing to see how much iron can be dissolved into these materials and hence how blue they can be made.

Established in 2012 at the Slade School of Fine Art, UCL the museum aims to promote knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the role of material within thinking and making. The museum is concerned with the preserving, collecting, exhibiting and fostering understanding of material at the highest possible museum and scholarly standards.

Exhibits can be anything that relates to material: a finished product in its own right or an unprocessed raw material. They can draw attention to substances or components with certain physical properties used in production or manufacture.

The museum, H 460mm x W 660mm x D 270mm has the potential to travel but will normally be situated on the ground floor of the Slade.

Close

Close