Reflections from the first meeting of IoMH Special Interest Group in Psychological Trauma

By iomh, on 6 July 2022

This blog was written by UCL Division of Psychiatry PhD Student, Ava Mason.

The Institute of Mental Health (IoMH) Special Interest Group in Psychological Trauma is an interdisciplinary group of UCL researchers and clinicians from our partner NHS trusts. The meetings within this group aim to provide opportunities for collaboration between academics and clinicians, raise the visibility of trauma research at UCL and develop a UCL-wide ‘trauma strategy’. The first meeting included a range of hot topic talks, whereby each of the members discussed their research or clinical focus to the 150 attendees.

Dr Michael Bloomfield who chaired the event explained how one third of individuals who experience psychosis have also experienced previous childhood trauma. Reporting recent results from a large multi-site international study, he stated that 69.9% of participants who had experienced childhood trauma and had an at-risk mental state also had undiagnosed PTSD or complex PTSD. Relating to trauma experienced by children in care, Dr Rachel Hiller discussed key work currently being conducted investigating transdiagnostic predictors of mental health outcomes. This work could help to develop feasible and effective interventions and inform future service decision making for those in care.

The next hot topic was presented by Shirley McNicholas, who discussed multiple ways in which trauma informed care could be implemented, specifically referring to the women-only Drayton Park crisis house. She discussed how the environment can be used as a therapeutic tool to help people feel safe, while environment seen as punishing and criminalising negatively impacts women who require support. Trauma informed care also involves helping people connect the past to the present to intervene appropriately, reducing misdiagnosis, inappropriate care planning and compounding self-isolation and shame. A trauma informed organisational approach within Camden and Islington was then emphasised by Dr Philippa Greenfield.

She discussed the need to increase trauma informed culture embedded within all services and wider communities. This involves challenging inequality and addressing secondary trauma in the workforce and with patients and acknowledging the impact of adversity and inequality on physical and mental health. Currently, trauma informed collaborative and Hubs have been established to help manage change from within organisations and monthly trauma informed training is being run for staff, service users and carers.

Dr Jo Billings highlighted the considerable impact of occupational trauma within the workplace. Within the peak of the pandemic, this phenomenon had increased research focus, with studies finding 58% of workers meeting criteria for anxiety, depression, or PTSD. Within global research on police workers, 25.7% drank hazardously and 14.2% met criteria for PTSD. Focusing on UK research on 253 mental health professionals, high rates of burnout and secondary traumatic stress have been reported. Strategies that could mitigate this include increased reflective supervision, minimising work exposure where ethically possible and identifying individuals who may be at most risk.

Relating to plasticity enhanced psychotherapy, Dr Ravi Das discussed the importance of research aiming to improve synergy between drug and psychological treatments. Current medication for PTSD does not target causal mechanisms of PTSD, which may explain why many individuals with PTSD do not find medication effective. Drugs like Ketamine block NMDA receptors critical to memory formation and restores lost synaptic plasticity, preventing trauma memories from stabilising. This allows the memory and cognitions of the event to be altered during therapy. Future research should focus on specific medication that target mechanism of change itself to increase the effectiveness of PTSD treatments.

Dr Talya Greene discussed the impact of mass trauma, whereby the same event or a series of traumas affect many people at the same time. The current health system is not built to provide support to many individuals at once following an event, especially when the health workers themselves may be affected by the incident. Additionally, those that are affected by the event vary in many ways, from their cultural, mental health and trauma backgrounds to the way in which they were mentally or physically affected by the event itself. Focus is needed on the effects of early trauma responses on future health outcomes, and how to target groups that don’t normally access support due to physical difficulties or cultural background. Additionally, the current evidence base needs to be increased to see what may be effective specifically in the context of mass trauma settings.

Dr Mary Robertson and Dr Sue Farrier discussed various specialist services within Camden and Islington. One of these was the traumatic stress clinic, working with patients who have a history of complex trauma, including trafficking victims, war and conflict refugees, and individuals with a history of child abuse. The service helps to stabilise the individual before considering which trauma focused individual or group intervention to provide. Additionally, Operation Courage is the term used to describe several Veterans specialist mental health services. They offer comprehensive holistic assessment, referral to local services and in house social support, pharmacological and psychological treatment. These veteran services aim to offer quick support, working alongside statutory and non-statutory agencies where care is shaped by the service users. Alcohol and substance misuse is not seen as a barrier for treatment access, and services also provide peer support and consultation for carers and family.

The audience raised some relevant questions for the panel to discuss, such as how best to strengthen clinical and academic collaborations. Feedback suggested the need to quickly produce trauma informed digestible research that can be rapidly synthesised and relayed back to clinicians. The main barrier to this being a fundamental need for more funding to create a working relationship between academic and clinical services. Within under resourced clinical services, a network approach is required so clinicians can codevelop research questions with other colleagues and trainees to reduce research workload. The need to listen to the voice of marginalised groups within research was also discussed. This involves building a trusting relationship between researchers and BAME groups, to collaborate with service users and consider the impact of historical racism, family dynamics and cultural impact within trauma research. The panel also suggested ways to reduce occupational trauma through having a cohesive team where people can build resilience and support through integrating coping mechanism individually and as a team.

Lastly, Ana Antunes-Martins discussed the Institute of Mental Health Small Grants, providing funding for interdisciplinary teams of all mental health areas, prioritising applications focusing on mechanistic understanding of mental health.

The next meeting will focus more on some of the relevant points raised within this meeting, as well as potential collaboration opportunities. To find out more about this group (and future meeting dates) please visit: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/mental-health/special-interest-group-psychological-trauma

Loneliness and isolation in young people: how can we improve interventions and reduce stigma?

By iomh, on 5 May 2022

This blog was written by first-year UCL-Wellcome Mental Health Science PhD Student, Anna Hall, for Mental Health Awareness Week 2022. This year’s theme is on Loneliness.

There are few people who have never experienced loneliness, whether it was a brief feeling that naturally passed or a more chronic experience we had to work to overcome. In 2018, the BBC Loneliness Experiment found that, of all age groups in the UK, young people aged 16 to 24 years report feeling the loneliest. Loneliness is a distressing feeling, and chronic loneliness is associated with a range of physical and mental health conditions, including heart disease and depression. It is therefore important that we reduce these feelings in young people, and I was interested in understanding how we can best achieve this.

I had the exciting opportunity to work with Dr Alexandra Pitman who co-leads the Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health Network. As I became more familiar with existing research, it became clear that few loneliness interventions focus on young people in the general population. Those that do have varying effectiveness and young people are not very drawn to them. Given the high prevalence in this age group, I was struck by this lack of interventions and motivated to contribute to improvement.

BBC Loneliness Experiment

We analysed data from 16 to 18 year olds who answered two questions regarding loneliness interventions in the BBC Loneliness Experiment. This was a large online international survey released in 2018 with wide media attention. This qualitative method of analysis, analysing free-text responses, was another element of the project which particularly excited me. I have always used quantitative methods in my research, using statistics to analyse numerical data, so I was interested to see what we can learn from qualitative methods. I quickly learnt that these methods are incredibly insightful!

We found that adolescents suggested strategies very similar to those currently employed in loneliness interventions, such as increasing social connections, changing the way they think about themselves and others, and improving social skills. However, many adolescents also described strategies to change how they experience solitude, including changing the way they think about spending time alone. As adults, we recognise that enjoying time alone is an important life skill. We may assume that this way of thinking is too mature for adolescents, but our study suggests otherwise. It may therefore be beneficial for interventions to incorporate strategies which highlight the distinction between spending time alone and feeling lonely, and provide adolescents with ways to enjoy solitude.

The findings from my project have not only been insightful in terms of helping to improve loneliness interventions but have also helped me to think more about the way we approach mental health research more broadly.

Whilst we were able to group the responses into four main categories, the specific details of responses varied. Every individual had their own ideas about what was helpful, and what was helpful for one person was specifically unhelpful for another. I therefore think that personalisation of interventions for loneliness may be beneficial. This is a huge challenge for researchers and clinicians as we are unclear exactly what works for who and why, and this is a complex question to answer. However, I believe it is an important goal if we are to develop effective interventions for loneliness and mental health difficulties.

We also found that some adolescents described hiding their true feelings of loneliness, possibly in fear of stigmatising views from others. As I learnt in my project, researchers are best able to understand loneliness and mental health by talking to the individuals we are trying to help. These individuals are also important in helping us design our studies and interpret results. However, many people may not feel comfortable talking about their experiences due to fear of stigmatising views. This presents a barrier to conducting applied research and developing effective interventions, and one that we must overcome.

Finally, this project taught me the importance of using different methods in mental health research. I completed my MSc in Cognitive Neuroscience and have always been an advocate of brain imaging and statistics, believing that mental health research should always use numbers. From this project, I have learnt that qualitative methods are vital if we are to understand mental health. We get caught up in conducting good science and following our research ideas that we can forget we are ultimately mental health researchers aiming to help individuals who are lonely or struggling with mental illness. Qualitative methods allow us to better understand individuals’ experiences and explore what would help them. This is not to say that quantitative methods are not useful. Whilst it will be challenging, I believe that mental health research must adopt an interdisciplinary approach and combine methods to progress our understanding and improve care.

Being a part of the UCL-Wellcome Mental Health Science PhD has meant that I am already surrounded by passionate researchers who are trying to tackle these challenges. I have been encouraged to undertake projects exploring topics and methods which I have no prior experience. Whilst the prospect initially seemed daunting, it has been hugely rewarding; I have been able to develop my skills and ideas and have been supported every step of the way. My previous enthusiasm for cognitive neuroscience has not waned but I am now considering how I can incorporate these new methods to complement my research ideas. We have also been lucky enough to gain clinical experience in mental health services around London, exposing me to the challenges faced by mental health services and patients trying to access support. This has been invaluable in encouraging me to consider how best to conduct research to benefit patients and contribute to public policy to improve service provision.

Above the professional aspects, the programme has bought me together with a cohort of inspiring researchers and new friends. A PhD can be a lonely experience. I am grateful to be part of a programme that fosters a supportive and friendly environment within the cohort and the wider academic community, and I am excited to meet everyone who joins us along the way.

Mental Health Awareness Week (MHAW) takes place every year during the second week of May, hosted by the Mental Health Foundation. This MHAW will focus on raising awareness of the impact of loneliness on our mental wellbeing and the practical steps we can take to address it. Follow online via #MHAW2022 #IveBeenThere

Further links:

University Mental Health Day

By iomh, on 2 March 2022

By Dominic Wong, UCL Student Support and Wellbeing and Project Coordinator on UCL’s submission for the University Mental Health Charter.

The mental health landscape in higher education has changed significantly in the past few years. This is partially due to culture shifts in society, but the quickest change has been during Covid with more and more students and staff reporting mental health issues. This has led to universities seeing a huge demand for their support services. This increased demand has forced universities to take mental health more seriously by making it a strategic priority implementing a whole university approach.

University Mental Health Day (3rd March 2022) brings together the student community in an effort to make mental health a university-wide priority across the UK. It’s perhaps the perfect time to share my experience of project managing UCL’s submission for the University Mental Health Charter Award, but first here’s a little background to the Charter and Award.

University Mental Health Charter Award (UMHCA)

The Charter framework provides a set of evidence-informed principles to support universities across the UK in prioritising student and staff mental health. Among other principles, the Charter lays out details of how to create effective support services alongside an environment and culture that promote good mental health for the whole university community. As part of UCL’s submission, we had to draft a 20,000-word document about its approach to each of the 18 themes of the Charter.

My experience

I was attracted to this role as it aligns very well with my background of completing a PhD in Health Psychology, and working as a Student Adviser, Teacher, Examiner, and Project Manager. I know from personal and professional experience that mental health issues such as chronic stress can be extremely damaging but can be overcome with support. For example, as part of my PhD, I ran a successful 7-week online workplace stress intervention using CBT practices that improved employees’ self-efficacy, social support seeking behaviours, job satisfaction, sickness absence, and physical health symptoms.

Since I started this role last June, UCL has made great strides in its journey down the path of submission. As the Award is based on a university-wide approach, I’ve not done this alone – colleagues from all across UCL have contributed. For example, we’ve had meetings with representatives from each of the 11 faculties, sharing their experiences of all things related to mental health and wellbeing, from enhancing personal tutor support to creating more social spaces. But this has not only been a staff endeavour. We thought it best for UCL students to be involved fully and as such many of the Sabbatical Officers have shared their feedback on our submission and worked together with our Staff domain leads on different sections of our report. It’s been great to see all the examples of excellent practice happening in each faculty and at the university as a whole. Of course, given the sheer size of UCL, the broad range of faculties (with their own strong identities) and the amount of people and teams involved in providing support (but not always being aware of what each are doing) there are also many challenges. However, it’s been humbling and heartening to see colleagues giving honest appraisals of our shortcomings and discussing with them about what we can do to overcome them.

Example challenge and moving forward

Although Student and staff wellbeing strategies are aligned and monitored through one implementation oversight group, the teams that run them are separate. Following UCL’s submission to the award, our current UMHC Working Group (which already includes senior faculty reps) will become the ‘UMHCA Implementation Group’ and will be given a new mandate to deliver the university-wide continuous improvements required by the UMHC (guided by the charter framework and award team feedback).

The path towards good mental health

It’s been a tough task to condense all that information down to 20,000 words, but the editing process has been a very satisfying one, not least because it involved negotiation between colleagues who were obviously fully committed to the project and passionate about the mental health and wellbeing of our community.

I hope the submission process for this award and any positive changes made as a result, help guide students and staff down their own path to good mental health.

Read more about the University Mental Health Charter Award at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/mental-health/university-mental-health-charter-award

University Mental Health Day is taking place on 3rd March 2022. You can take part online at #UniMentalHealthDay or attend UCL Student Support and Wellbeing event

UCL mental health research in older adults during COVID-19

By iomh, on 22 October 2021

By Dr Kathy Liu, MRC Clinical Research Training Fellow, UCL Division of Psychiatry

By the first national lockdown on 26 March 2020, many were aware that COVID-19 and related restrictions have a disproportionate impact on older adults and individuals affected by dementia. UCL mental health researchers responded rapidly to try to understand how older adult mental health and dementia wellbeing were affected and what should be done. This blog summarises some of the insights and research contributions we made.

Higher infection and death rates from COVID-19

An international study led by Dr Aida Suárez-González from UCL found that by August 2020, people with dementia made up around a third (31%) of COVID-19 related deaths in the UK1. The study group, including UCL researcher Prof Gill Livingston, linked this to high death rates in care homes where most residents have dementia. In the UK, older people were admitted to care homes without knowing if they had COVID-19 or not. These individuals were also often not allowed to access healthcare and were isolated and confined, with visitors to care homes banned.

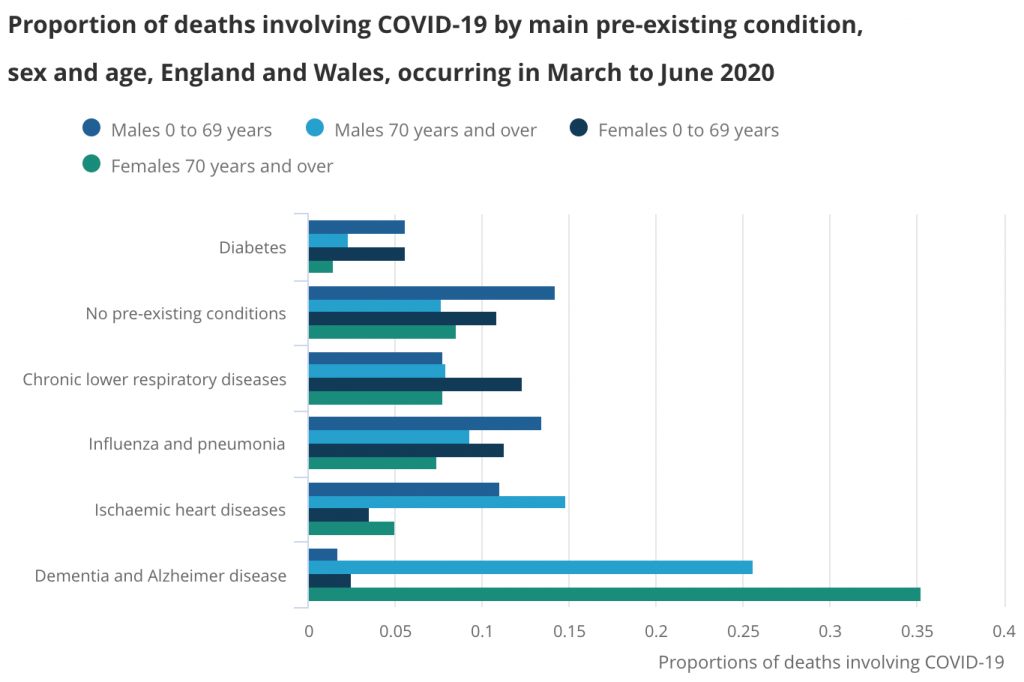

Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the most common main pre-existing health condition in deaths involving COVID-19 between March and June 2020. Published by the Office for National Statistics.

Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the most common main pre-existing health condition in deaths involving COVID-19 between March and June 2020. Published by the Office for National Statistics.

Negative impact of COVID-19 restrictions on dementia wellbeing

To assess the effect of COVID-19 isolation measures on people with dementia, Dr Suárez-González, Prof Livingston, and colleagues analysed findings from existing studies2. They found that isolation measures had a negative impact on memory and thinking and mental health, with almost all studies reporting a new onset or deteriorating distressing behavioural or psychological symptoms in people with dementia.

Increased prescribing to treat behavioural or psychological symptoms

Antipsychotic drugs can be used to treat distressing behavioural or psychological symptoms in dementia, such as agitation and psychosis, when non-drug approaches have failed. However, they have limited effectiveness and serious side effects. Prof Robert Howard from UCL led an investigation and found that rates of antipsychotic prescribing increased in people with dementia in England from March-July 20203. This highlights the need to monitor and reduce the rates of antipsychotic prescribing once COVID-19-related risks have decreased.

Monitoring COVID-19 infection and death rates in mental health hospitals

Infection control measures in hospitals are important to minimise COVID-19 infection and deaths in patients and healthcare staff. Prof Gill Livingston led a study including UCL researchers Dr Andrew Sommerlad, Dr Louise Marston and Dr Kathy Liu, and many NHS doctors, to measure infection and death rates in patients aged over 65 years or diagnosed with dementia between March-April 20204. Patients had been admitted to one of 16 psychiatric wards in NHS mental health hospitals in London. Data could be obtained rapidly as COVID research regulations allowed the use of anonymised hospital patient data without the need for individual consent, and regulatory bodies prioritised applications for such studies. The NHS doctors on the team also contributed their time and made efforts to help collect data rapidly. The study group found that mental health hospitals experienced a delay in accessing personal protective equipment (PPE) and COVID-19 tests compared to other hospitals. This likely contributed to higher infection (38%) and death (15%) rates compared to community levels, despite the government policy of parity of esteem for physical and mental health.

Mental health hospitals experienced delayed access to PPE and COVID-19 tests during the first wave. Image by leo2014 from Pixabay.

Mental health hospitals experienced delayed access to PPE and COVID-19 tests during the first wave. Image by leo2014 from Pixabay.

After the study findings and recommendations were published, the research group repeated the measurements during the second pandemic wave between December 2020-February 20215. There were improvements in infection control measures and better outcomes for patients. Infection rates were lower (25%) with correspondingly fewer deaths. Vaccinations may offer additional protection against COVID-19 in future, but measures such as regular testing of inpatients remain appropriate, as a significant proportion of COVID-19 positive patients were asymptomatic (29%).

Reduced face-to-face approaches and adaptations by mental health services

UCL researcher Dr Rohan Bhome led a study6 to explore the perspectives of staff who worked in older adult mental health services between April and May 2020. The study highlighted areas that mental health services could develop to address staff and patient wellbeing during the pandemic. The team, including UCL researchers Dr Jonathan Huntley, Christian Dalton-Locke and Prof Gill Livingston, found that staff were concerned about barriers to infection control in hospitals and a lack of usual support for older people who lived at home. Staff responded positively to the shift to increased remote working but noted that some patients could not use the technology required for remote assessments.

Staff working in older adult mental health services were concerned that some patients could not use the technology required for remote assessments. Image by Sabine van Erp from Pixabay.

Staff working in older adult mental health services were concerned that some patients could not use the technology required for remote assessments. Image by Sabine van Erp from Pixabay.

Negative impact on carers

Most family carers, including those caring for older people and individuals with dementia, are unpaid. Prof Gill Livingston was part of a team that published a report highlighting the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family carers7. Many carers increased their care hours during the pandemic. Access to support services, such as respite care and day centres, was severely restricted or more usually stopped. Some carers were also reluctant to continue with home care services due to concerns about the risk of infection. The report offered recommendations and policy considerations to improve outcomes for all carers.

The wellbeing of carers was often negatively affected by the pandemic. Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.

The wellbeing of carers was often negatively affected by the pandemic. Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.

Directions for future dementia research

UCL researchers led by Dr Kathy Liu, with Dr Andrew Sommerlad, Prof Robert Howard and Prof Gill Livingston were part of a group that carried out a research update on dementia wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic8. The project was commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care Dementia Programme Board. It incorporated findings from over a hundred studies on dementia wellbeing and COVID-19, using a framework published by NHS England (see figure below). From the findings, the group collectively identified key knowledge gaps to help researchers and organisations direct future research.

Published by NHS England 2020

Published by NHS England 2020

Conclusion

UCL mental health researchers have worked rapidly to try to understand the impacts of the pandemic on older adults and individuals affected by dementia and make recommendations. Our future work will aim to explore and resolve outstanding research questions to improve the quality of life of these individuals and their carers.

REFERENCES

- Suárez-González, A. et al. Impact and mortality of COVID-19 on people living with dementia: cross-country report. https://ltccovid.org/2020/08/19/impact-and-mortality-of-covid-19-on-people-living-with-dementia-cross-country-report/ (2020).

- Suárez-González, A., Rajagopalan, J., Livingston, G. & Alladi, S. The effect of COVID-19 isolation measures on the cognition and mental health of people living with dementia: A rapid systematic review of one year of quantitative evidence. EClinicalMedicine 39, 101047 (2021).

- Howard, R., Burns, A. & Schneider, L. Antipsychotic prescribing to people with dementia during COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 19, 892 (2020).

- Livingston, G. et al. Prevalence, management, and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infections in older people and those with dementia in mental health wards in London, UK: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 1054–1063 (2020).

- Liu, K. Y. et al. Infection control and the prevalence, management and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infections in mental health wards in London, UK: Lessons learned from wave 1 to wave 2. Undergoing peer review for publication (2021).

- Bhome, R. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Older Adults Mental Health Services: a mixed methods study. bioRxiv (2020) doi:10.1101/2020.11.14.20231704.

- Onwumere, J. et al. COVID-19 and UK family carers: policy implications. Lancet Psychiatry 8, 929–936 (2021).

- Liu, K. Y. et al. Dementia wellbeing and COVID-19: Review and expert consensus on current research and knowledge gaps. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry (2021) doi:10.1002/gps.5567.

UCL Mental Health Research at the time of COVID

By iomh, on 12 May 2021

This blog was written by Ana Antunes-Martins, Research Coordinator for UCL Institute of Mental Health.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had multiple effects on mental health, some of which are likely to be long-lasting. UCL mental health researchers have been busy investigating how the infection affects the nervous system, how we adapted to life in lockdown, and how we have been coping with the hardships brought by the pandemic. This blog post is a broad overview of UCL’s contributions to the fight against the ‘mental health pandemic’ over the last year. For more in-depth discussions of specific mental health topics and COVID, read our series of blog posts published on the IoMH website over the last year.

Learning from previous coronavirus outbreaks and early COVID-19 data, in July 2020, Jonathan Rogers and Tony David suggested that lasting mental disorders may follow severe COVID-19 infection in some patients (1). They also found that, while thoughts of suicide and self-harm have shown increases in some groups around the world (e.g., the young and those suffering from the viral infection), suicide has not generally increased (2). Perhaps increased social cohesion – the feeling that we are stronger together – has been a protective factor.

But we cannot necessarily rely on this. A group of clinical academics led by Michael Bloomfield banded together to form the COVID Trauma Response Group. The group recommends that COVID survivors should be monitored to address risks of PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Long-COVID sufferers also describe mental health symptoms (fatigue and so-called ‘brain fog’). Two NIHR/UKRI-funded studies will follow Long-COVID patients to understand how the disease progresses, whether it can be treated, and who is most vulnerable. One of these studies, led by the MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL, will focus on adults, while the other, led by Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, will focus on those who contracted the virus as adolescents.

Beyond the direct effects of the virus, the pandemic caused sudden changes to our lives and livelihoods and put massive strains on society. To understand how these challenges impacted our mental health and wellbeing, UCL researchers conducted interviews and surveys with large numbers of people. Some of these studies were added to ongoing research, while others were set up from scratch. For example, studies at the UCL Centre for Longitudinal Studies are taking advantage of birth cohorts (samples of the population followed regularly since birth) to investigate how mental health and behaviours compare to pre-pandemic levels and change as the pandemic progresses. Another large study is the COVID-19 Social Study, led by Daisy Fancourt, which was set up in March 2020 to keep track of the feelings and habits of 70,000 adults in the UK every week.

These types of studies provided snapshots of our lives during the pandemic: how depressed, worried, lonely, and anxious we felt and how much we slept, exercised, and drank alcohol, and whether we ate our 5-a-day (3,4). Most importantly, because the studies followed such a large slice of the population, researchers could pinpoint which groups struggled the most. Amongst adults: women, younger adults, and those facing financial hardship, those with mental illnesses before the pandemic, and those who were lonely fared poorly in several mental health and wellbeing measures.

UCL researchers homed in on these groups. In many cases, people in these groups already suffered from poor mental health before the pandemic, and the pandemic just made it worse: women’s psychological distress was worsened by increased childcare responsibilities (5), young people were more affected by job uncertainties and worried about the future and consequently more depressed, anxious, and lonely (6), those with precarious working conditions had worse physical and mental health outlooks, and even increased mortality during the first year of the pandemic (7).

The sudden changes brought by the pandemic were particularly challenging to those who already had mental health disorders and saw their support networks and access to healthcare compromised. The Mental Health Policy Research Unit (MHPRU), led by Sonia Johnson, is researching ‘what works’ in mental health services. For example, a literature review of mental health services worldwide, identified the evidence needed to inform policy and best practice (8). Central to this research is the voices of those with lived experience. In this spirit, the MHPRU and the Loneliness and Social Isolation Network work with ‘experts by experience’ to co-develop surveys and interviews to understand the specific challenges faced by the patients and how they can be supported, especially in navigating remote health care (9).

Loneliness is a big player in poor mental health. The good news is that maintaining remote contact with friends and family (10) and engaging in arts (11) may be helpful tools to combat loneliness and improve mental health. The ‘Community COVID’ study led by Prof Helen Chatterjee will address how well ‘creative resources’ work to improve mental health and how we can make the most of them.

Children and adolescents had their routines and social lives completely changed by school closures. Researchers at the UCL Institute of Education and the Anna Freud Centre are devoting significant efforts to understanding pupils’ experiences from different ages and socio-economic backgrounds (12,13). They ask who coped better and worse (and why), what pupils found most upsetting, what they did to improve their moods, how families managed, and whether school staff could cater to children’s wellbeing remotely. But research is only worthwhile if it can help people, and these researchers are doing precisely that, by producing up-to-date homeschooling resources and lay summaries to help families support their children’s wellbeing.

So, what next? Fourteen months since the beginning of the pandemic, the UCL mental health research community has generated invaluable data and resources to help society and individuals cope better and hopefully, to some extent, reduce the long-term repercussions of the pandemic. Lessons learned to date have informed clinical mental health practice, education, social and community support strategies, and will have impacts well-beyond the pandemic. Of course, there are many unanswered questions, and studies that are just starting, and we look forward to hearing what this new research holds.

References

- Rogers, J. P. et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 611-627, doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0 (2020).

- Rogers, J. P. et al. Suicide, self-harm and thoughts of suicide or self-harm in infectious disease epidemics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 30, e32, doi:10.1017/S2045796021000214 (2021).

- Villadsen, A. et al. Mental health in relation to changes in sleep, exercise, alcohol and diet during the COVID-19 pandemic: examination of four UK cohort studies. medRxiv 03.26.21254424; doi:https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.03.26.21254424

- Saunders, R., Buckman, J. E. J., Fonagy, P. & Fancourt, D. Understanding different trajectories of mental health across the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 1-9, doi:10.1017/s0033291721000957.

- Xue, B. & McMunn, A. Gender differences in unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK Covid-19 lockdown. PLoS One 16, e0247959, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247959 (2021).

- https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ioe/news/2021/apr/more-half-16-25-year-olds-fear-their-futures-and-job-prospects

- https://www.ifow.org/resources/the-good-work-monitor

- Sheridan Rains, L. et al. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 1-12, doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01924-7.

- Gillard, S. et al. Experiences of living with mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: a coproduced, participatory qualitative interview study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol, doi:10.1007/s00127-021-02051-7 (2021).

- Sommerlad, A. et al. Social relationships and depression during the COVID-19 lockdown: longitudinal analysis of the COVID-19 Social Study. Psychol Med, 1-10, doi:10.1017/S0033291721000039 (2021).

- Mak, H.W. et al. Predictors and Impact of Arts Engagement During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analyses of Data From 19,384 Adults in the COVID-19 Social Study. Front Psychol, doi: 3389/fpsyg.2021.626263 (2021)

- https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ioe/research/covid-19-research-ucl-institute-education/research-related-covid-19

- https://www.annafreud.org/coronavirus-support/our-research/

Architecture and Mental Health – How built environment and healthcare professionals can work together to improve psychiatric environments

By iomh, on 11 May 2021

This blog was written by Dr Evangelia Chrysikou, Lecturer at The Bartlett School of Sustainable Construction, Program Director of the MSc Healthcare Facilities at UCL and medical architect.

Foucault’s History of Madness (1964) was the book that triggered my interest on spaces for psychiatric patients. Even though the spaces of confinement where not the purpose in the book, being an architect with skills on visualising spaces, those asylum buildings provided an incredibly dystopian scenery for the actual context. It was clear to me that those spaces, even if that were not necessarily the intention, were facilitating the alienation of mentally ill people at multiple levels, from social to personal. Looking at the plans and the narratives one could understand that deprivation and inequality were principles embedded in their architecture. So, what was the situation now, what was the physical context of mental illness? Did the movements of anti-psychiatry or the efforts for psychiatric rehabilitation have a tangible effect in stopping this coercive paradigm of neglect and at the same time help facilitate the change that was happening at that time in the care for psychiatric patients? This was in the mid-nineties, at a period where in several parts of Europe the old asylums would be gradually replaced by smaller psychiatric facilities, mostly but not necessarily in the community, in an uneven journey of trial and error. I started working with the teams that moved the patients from the notorious Leros asylum back to the community. I soon realised that the available literature was mainly from health services research rather than architecture. The new paradigm advocated for small (but then how small?), domestic (but what does this actually mean?) structures of various types and purposes, preferably in the centre of their catchment area with welcoming accents of tablecloths and cutlery. Those descriptions reflected how a healthcare professional would describe spaces but would leave a lot unanswered in terms of an architectural inquiry. Taking people from Leros asylum to their original places in mainland Greece was a task for the psychiatrists. How they would bring people back from a courtyard where the single tree was always leafy –a eucalyptus tree– so patients did not know what the word “autumn” meant and they had forgotten the seasons. How would they explain inner city traffic jams and crossings to somebody who left their rural village in the thirties, or modern flats and electrical appliances? How would these people be transferred into the modern era and in a busy urban context that they had never met? What sort of buildings should facilitate this transition?

This is where my research started. I had to look at the available provision first in Greece and then to Belgium, the UK and France. I could see a variety of structures, urban or rural, embedded in the community or isolated, small or multi-storey and complex, with different levels of security, interaction and stimuli. There was no unified model of care and that was apparent if one looked at the building stock. My research initially looked at these various options and then I concentrated on understanding the therapeutic spaces available for the acute spectrum of mental illness. I involved patients and staff and sought to understand their perspectives on how such spaces should be shaped. It was the first time that a researcher asked psychiatric spaces to give feedback about the place and space of the wards. At the same time I evaluated the architecture of spaces using theories of space and place making. My research generated various tools: a very useful one and very simple to use was a checklist that classified the psychiatric buildings in terms of domesticity vs institutionalization and the SCP model for the planning and evaluation of psychiatric spaces (Chrysikou, 2014). For the benefit of PhD researchers, you might be interested to know that the model was developed from my PhD and has shaped much of my research since as well as providing a useful tool for other research projects I have been involved over the years, including my Marie Curie Individual Fellowship project (Chrysikou, 2019). This model offers a three dimensional perspective of analysing psychiatric buildings in relation to their therapeutic purpose. Each axis refers to a different priority –safety and security, competence and personalisation and choice—and at the same time refers to a different era in the design for mental health –the coercive, the medical and the psychosocial (Figure 1). That way, professionals and stakeholders involved in the planning, the design and the evaluation of such premises can have context and references, even for simple decision-making. For example, in the case of a forensic facility we need to focus more on safety and security as dangerousness might have a significant impact, but at the same time we have to think and acknowledge clinical needs and the ultimate aim of psychosocial rehabilitation and the principles of valorisation that could still be suitable for forensic accommodation. So, we would have secure windows but at the same time we could prioritise views to green and blue. The tools developed would help evaluate the environment of the wards in relation to their surroundings, the closed space within the ward and even details.

When I first conducted research in the UK in the late nineties, I could detect remnants of the previous mental health care model, the medical model, in the architecture of the wards. The older wards might be situated in hospital premises and even if they had evolved they still retain general ward typologies. Those co-existed with some new typologies, experimenting on what a psychiatric ward should be. Those would demonstrate investment in design and innovation. This period of experimentation has been replaced by a more uniform reality supporting single ensuite rooms, light spaces and the introduction of visual art. Yet, at the same time we could detect some institutional re-introductions in the name of anti-ligature: bathroom fixtures and fittings that cannot cause harm but are quite uncomfortable to use, heavy, immobile furniture very similar to what the old asylums would have, absence of door panels or drawers in storage units, making clutter more visible. To a system that is understaffed such practices prove a viable solution yet at the same time convey the message that patients are not to be trusted. They are also present in North American psychiatric hospitals but we do not see them in the European equivalents, making the comparison inevitable. More cross-country comparisons would be important to help us learn from those differences. Transdisciplinarity would be another critical element for future research. As psychiatric environments have to support a variety of functions and purposes, they present challenges that other types of healthcare environments do not necessarily have. Transdisciplinary and user-inclusive research would be our best chance to capture that complexity. Researchers from health disciplines have to collaborate with researchers who are familiar with built environment perspectives and grow the area in between.

References

Fouqault, M. (1964). Histoire de la Folie, a l’ age classique. Paris: Plon

Chrysikou, Ε. (2014). Architecture for psychiatric environments and therapeutic spaces. Amsterdam: IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-61499-459-6

Chrysikou, E. (2019). Psychiatric institutions and the physical environment: combining medical architecture methodologies and architectural morphology to increase our understanding. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, vol. 2019, Article ID 4076259, 16 pages, https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4076259

Figure 1: The SCP model

Biography

Dr Evangelia Chrysikou is Lecturer at The Bartlett School of Sustainable Construction, Program Director of the MSc Healthcare Facilities and medical architect. She is Vice-President of the Urban Health Section (EUPHA) and RIBA Chartered Member. She specialises in healthcare facilities, holding a rare PhD on mental health facilities from UCL and a very prestigious Marie Curie H2020 Individual Fellowship. She has been actively involved in policy, being Coordinator on D4 Action Group of the European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP on AHA) of the European Commission (EC). Evangelia has received several international awards for her healthcare architectural projects and her research. She authored the national guidelines for mental health facilities in the community for Greece on behalf of the European Union. Additionally, she authored the books ‘Architecture for psychiatric environments and therapeutic spaces’ and ‘The social invisibility of mental health facilities’, is a healthcare architecture editor, reviewer, active member of several professional and scientific associations and TED-MED speaker.

Starting a PhD in the middle of a pandemic by Humma Andleeb

By iomh, on 18 March 2021

This is a series of blogs about my experience of the UCL-Wellcome Mental Health Science PhD programme. It will cover applying for the programme, the interview and lead up to enrolment stage of the programme as well as my experience of the programme and my PhD. I am publishing these blogs for prospective students in response to the queries I have received about the programme in response to my Twitter thread on successfully securing a place on the programme.

Over the last year, all of us have had to drastically alter our lives in some way, whether that be home-schooling your children, working from home, practising extensive social distancing and hygiene in public spaces or staying at home for extended periods of time.

Just days before the first lockdown was announced in March 2020, I had been offered a place on the UCL Wellcome PhD programme in Mental Health Science. Amongst the chaos, with the ever-extending lockdown, it was hard to plan or think about the future not knowing what would unfold over the coming months. I was increasingly anxious as people started losing their jobs facing unemployment without financial support, here I was about to leave a secure job to pursue a PhD. Honestly, I had to question whether it was the right time to take on a PhD and whether I was taking too much of a risk in the circumstances.

As the months followed and I was asked to shield whilst the pandemic picture grew much worse all over the world, my mental health took a rapid decline and my motivation dropped to an all-time low. Not being able to visualise the future and whether I would be able to take on the PhD if I would still be required to shield was causing me a lot of stress. Thankfully, the programme committee reassured me that they would find a way to accommodate the situation whatever it would be come September. Encouragingly, we were able to have a relatively relaxed summer and things seemed to be looking bright leading up to the start date but, quite suddenly, things started to worsen as schools opened in September and universities were set to open campuses for students. Nevertheless, I handed in my notice and began preparing for this new and once-in-a-lifetime venture.

Before the start, we were told by UCL that most teaching and work would be delivered online unless it was absolutely necessary to be on campus (for example, if you needed to be in a lab), as undergraduate students were to be prioritised for on-campus learning until at least January, but we would have the opportunity to meet the rest of the cohort and the committee at the UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience (ICN) for our weekly skills seminar (social distancing regulations in place, of course).

Considering all that was happening, it was helpful that we had the month of October to scope out potential rotation projects for the year with potential supervisors on the programme but still have the opportunity to attend a weekly seminar at the ICN. Knowing that most of our studies would be virtual until January (at the earliest), I made the decision to move back to my family home in the Midlands so I could spend time with my grandma and family (plus the bonus of saving money on rent!). I commuted to London for the weekly seminars and lunch with the rest of the cohort. This was short-lived as COVID-19 cases began to rise rapidly and the skills seminars switched to virtual when the November lockdown was announced, just as we started our first rotations. My first rotation was using existing datasets so could all be done virtually but as the rotations are short (10-12 weeks long), most projects were unable to offer data collection opportunities and if they were, these were currently all being done virtually. Essentially, everyone was in the same boat.

Overall, it was daunting starting a PhD in the middle of a global pandemic, especially in the context of giving up a well-paid job when unemployment was rising, but it was a now-or-never decision. I truly felt like I was at the stage in my career to take this on professionally, so it was a risk that was worth taking for me! My former colleagues at McPin were incredibly supportive in helping me navigate this change and gave me the validation I needed that this was something that was right for me. It really helped being able to meet with the rest of the cohort on Zoom and then in person weekly (especially great that we all got on so well). We immediately made a WhatsApp group to keep in touch and also met virtually on Zoom for the skills seminars. In my opinion, the most difficult thing has been working with a lab group that you work with every day but never getting the opportunity to meet with them. You end up in a sort of awkward position of having spent a lengthy amount of time being part of the lab, but there being this barrier of not knowing someone’s persona in real life or fully understanding the lab banter that you have never physically been a part of.

Interview for the UCL-Wellcome 4-year PhD Programme in Mental Health Science by Humma Andleeb

By iomh, on 2 March 2021

This is a series of blogs about my experience of the UCL-Wellcome Mental Health Science PhD programme. It will cover applying for the programme, the interview and lead up to enrolment stage of the programme as well as my experience of the programme and my PhD. I am publishing these blogs for prospective students in response to the queries I have received about the programme in response to my Twitter thread on successfully securing a place on the programme.

Having applied to the UCL-Wellcome Mental Health PhD programme at the end of January 2020 (read my blog post on applying here), I was shortlisted for an interview, much to my surprise. We were told that we would be presented with a 30-minute task that would consist of a series of abstracts and the interviewee would be asked to summarise the abstract in lay language for the general public. Following the task, a 30-minute interview would take place with a panel consisting of members of the committee.

At the time, COVID-19 was beginning to spread rapidly especially in London and we were given the opportunity to have a virtual interview or have a socially-distanced in-person interview. I opted for an in-person interview, due to personal preference, but as things escalated the weekend before the interviews were due to take place, we were all given the opportunity to have a virtual interview and reassured that there would be no impact on our outcomes if we did opt for a virtual interview. I decided to go ahead with the original plans and have an in-person interview.

Preparing for the interview

In preparation for my interview, I revisited my application form and looked up some online resources on how to prepare for a PhD interview. Looking back at my application, I focussed on areas that might interest the panel and areas that I could potentially expand on at interview. Using online resources that provided guidance and feedback from interview experiences helped to guide me in preparing for questions that I may be asked relating to the programme and my application as well as think about questions that I had about the programme and the university. However, I noticed that resources online tend to focus on specific PhDs with a specific supervisor and assume that you already have a thesis title; therefore, it’s important to note that this programme is different, in that it is a 1+3 programme and is for a generic Mental Health Science PhD, so there is less need to focus on specific background research in one area. The focus of the programme being interdisciplinary also comes into this, as collaboration across the three main themes (Mechanism, Population and Intervention) is heavily encouraged and forms the basis for the programme.

The interview

On the day of the interview, I got the bus from my South London home to Bloomsbury and walked to the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience where the interview was due to take place. As someone who is either very late or very early, I decided to make a conscious effort to be VERY early, so I arrived before the building had even opened! Thankfully, I didn’t have to stand outside for very long before the receptionist arrived, and I had plenty of time to look through the notes I had made in the foyer area (after sanitizing my hands of course!). The panel members began arriving and there was an interview scheduled before mine, but time went really quickly as I skimmed through my preparation notes and before I knew it, it was time to start the task. Whilst working on the task, I was anxious that I’d forget all my preparation for the main interview so it was a plus that all that was required of me was to summarise the abstract (I’m not sure I could have done anything more complex than that!).

Due to the nature of the unfolding pandemic, some of the panellists joined the interview via Zoom and others were there in person, but the room was set up to ensure that we could all communicate and see each other. Another thing that immediately stood out to me was that there was no daunting row of mean-looking panellists sitting across from the interviewee, ready to pounce on you. Instead, they all introduced themselves and gave some insight into their role on the programme and their job before outlining how the interview would go.

The interview itself felt like a conversation and all of my worries disappeared once I settled into the atmosphere and noticed the welcoming nature of the panel. Usually, I’d want the interview to end as soon as possible, but in this interview, I could have carried on talking about how great the programme was and its potential in encouraging collaborative research in mental health science. I was able to express my passion for interdisciplinary research, my previous research experience and my wider interests and hobbies. It was evident from the discussions that this programme is not just about academic achievement but also about ensuring students are well supported and trained in areas that will help shape our futures as mental health researchers and people.

I went in thinking of the panel as my colleagues and I felt like that was reciprocated by the panel. I left the interview on a bit of a (natural) high but, after a while, started kicking myself for some of the responses I gave – and things I had prepared that I did not have time to mention. But this is completely normal and there’s never enough time to share everything, so I was sure I did the best I could possibly have done and about an hour later, I forgot what had even been discussed! I had emphasised all I could to highlight why I felt I was an ideal student for this programme, now the decision was in the hands of the committee… all I could do at that point was to wait and hope.

As I share my personal experience, I’m aware that one person’s experience may differ greatly from the next, and other students in the cohort had virtual interviews, so they have kindly offered their reflections and experiences below:

Rosalind McAlpine: “I found the interview (surprisingly) enjoyable! I was slightly nervous about the pre-interview task, but the interview panel created an inviting and supportive atmosphere and my anxieties were immediately dissolved. As I was studying in America at the time, I completed my interview online and – prior to it starting – I was slightly apprehensive that things would be awkward due to the digital nature of the interview. However, the panel were clearly very experienced in conducting these sorts of interviews because I never felt as though I was being spoken over or speaking over someone, and the interview had a pleasant, reciprocal dynamic to it. I felt the questions they asked me were completely appropriate and allowed me to demonstrate why I wanted to join the programme and what I hoped to gain from it. Similarly, I felt comfortable in asking any questions that popped up and felt I was heard throughout.”

Thomas Steare: “Interviewing for a Wellcome-funded PhD at University College London is quite a big deal. Naturally I was nervous despite the numerous practice interviews I had done the week before. A great thing about the programme is its emphasis on supporting students and their well-being. This was evident throughout the interview as the panel made a big effort to be supportive and engaging. My anxieties quickly subsided when the interview commenced, and I soon enjoyed answering the interviewers’ questions and explaining why I was so interested in studying a PhD with a focus on interdisciplinary research methods.”

Giulia Piazza: “March 2020 was a strange month for many reasons. I was very surprised to be invited to an interview for the UCL-Wellcome 4-year PhD in Mental Health Science. I remember being incredibly nervous – I practiced a lot, and thankfully the panel was extremely welcoming and reassuring. I thought all questions were fair and relevant, and tried my best to explain why I so badly wanted to join the programme. If you have been shortlisted for an interview, here is my advice. Keep going despite technical mishaps. You might feel like you haven’t answered a question as best as you could have, but don’t lose hope throughout the interview. No one will be trying to trick you or get you to make a mistake: your interviewers really want every candidate to perform at their best, and they understand people will naturally be anxious on the day. Genuinely answer with your opinions, rather than thinking about what you believe the committee wants to hear. And lastly (and this is the hardest part), try not to be too hard on yourself!”

If you have been shortlisted and are currently preparing for your interview, my main tips would be:

- Use your application to guide your preparation. You have been shortlisted based on your application so use this to your advantage, and think of the interview as an opportunity to expand and reinforce what is included in your application

- Spend some time thinking about and preparing what you want to prioritise sharing in the interview

- Think about what the panel will want to know about you in order to gauge whether this programme is the right fit for your experience and passion for research and consider what they are looking for in a candidate

- Interviews don’t have to be daunting – framing them as a conversation with a new colleague about your previous experience and your aspirations, as opposed to giving answers to difficult questions from scary academics, might make it easier to prepare.

- Remember that there is more to you than just your academic achievements, and being a good candidate is about more than just having a longlist of experience and accolades

- Think about any questions you may have about the programme and use the interview opportunity to ask the committee members

Humma Andleeb is on the 4-year PhD programme in Mental Health Science at UCL. She has an academic background in biochemistry and neuroscience and previously worked at The McPin Foundation, using her lived experience of mental health difficulties to inform mental health research. She is passionate about patient and public involvement, specifically involving minoritised communities furthest away from the research field. She is a regular book reader, sourdough baker and lifestyle podcast listener. You can find her on Twitter: @HummaAndleeb

Suicide and COVID-19: ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’

By tonydavid, on 8 February 2021

Suicidologists, not famed for their optimism, are bracing themselves for an increase in suicide rates following the pandemic. Some have called it a perfect storm (1). It is not an easy subject to discuss for two main reasons. A person bereaved by suicide described it to me as like having a hand grenade explode in your living room. But precisely because suicide is such a singular event, it can only really be studied – in a way that useful lessons can be learned – from a distance, looking at large numbers and trends over time, by taking a kind of aerial view. The other reason is contagion. That’s why there are strict guidelines from the ‘Samaritans’ and others, on the way suicide is reported in the media (2) – which include avoidance of sensationalism, of the idea that the act is heroic, dwelling on methods, and that suicide was inevitable – for fear of copycats. Indeed the worst kind of newspaper reports did emerge early in the pandemic from India of people unexpectedly and violently taking their own lives after being told they had the virus but this did not continue and mercifully did not foretell of any similar trends. And I am conscious of even now having to be careful about my use of language even in the context of an article intended for a largely academic and educated audience (3,4).

Even asking about suicidal thoughts in a clinical context has made people anxious that it ‘puts thought into people’s heads’. Reassuringly, summarising several studies on this question, authors of a systematic review conclude that it is safe and can, as would be hoped, relieve distress (5). Our instincts and those motivating the bulk of mental health awareness campaigns tell us that it is good to talk. I should add that listening to someone who looks you in the eye and tells you of their intention to kill themselves feels like that grenade has just landed in your lap. It’s not an easy subject to talk or hear about.

Knowing of the possibility of suicide is arguably the uniquely human existential curse, as elaborated by 20th Century philosophers like Heidegger. But does being reminded of it really make a difference? Goethe’s hapless hero Werther takes his own life due to unrequited love. This sparked a minor craze in the mid 1770s of imitations by romantic young men donning the same blue coat and yellow waistcoat, and leaving the tell-tale eponymous novel by their sides. The moral panic that ensued has repeated itself many times with ‘13 Reason’s Why’ being a notable recent example (6).

Such outbreaks, spatial-temporal clustering to use the technical term, are fiendishly hard to prove statistically (7). In the age of social media and the internet the ‘where’ of a suicide hardly matters – unless within an institution like a prison or a psychiatric hospital – and the timing of a cluster is not obvious either; the next day, week, month? Indeed if there is to be an increase in suicides in the wake of this pandemic when should we expect it? Suicide statistics accumulate slowly and in the UK may wait months for a coroner’s verdict. Suicide is, thankfully, rare enough that it takes a while to see enough instances to say whether rates have increased even nationally, in comparison to, for example, the same time last year, even using provisional statistics.

Efforts have been accelerated around the world by the pandemic to provide real-time surveillance information so that rates can be tracked and if rising, perhaps mitigated (8). Early reports from Queensland Australia (pop approx. 5m) have made use of police reports to the coroner. There were tragically 434 suicides from February through August 2020, a rate which did not differ compared to the preceding 5 years (9). The social context of the suicides did not show any particular emphasis on say unemployment or domestic violence and just 36 were judged initially at least as being related to Covid-19 – in what way, was not made explicit. A study from Japan (10), which has suffered less than the most European countries from the pandemic, normally has an average of 1596 suicides per month but this dropped by 14% between February and June last year but then increased by 16% in July to October. Interpreting such fluctuation is tricky. Could it be that suicide was delayed during the first wave only to rebound or are we seeing a cumulative effect? The study authors wonder whether it has to do with the prospect of withdrawal of government financial support packages. Work in progress reported by the UK’s National Confidential Enquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health shows no increase in the monthly average from April-August 2020 compared with Jan-March (11). A similar picture of no increases is emerging from Norway (12) and preliminary data from the US (8).

The nearest we have in the UK to official rolling figures are monthly statistics on mortality in people under 18 (13). In the 82 days before the first lockdown in March 2020 there were a heart-rending 26 deaths by suicide compared with 25 in the first 56 days after, an post-lockdown increase in rate by about 40% but with a very wide margin of error such that the difference fails to meet conventional levels of statistical significance. A third of the young people were known to services.

Experience from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Hong Kong in the spring of 2003 – also caused by a coronavirus (14) showed an uptick of about 30% in deaths by suicide paralleling SARS mortality – over its 4 month course (15). This affected older women particularly, a group more prone to suicide in China for some reason unlike the general rule around the world that older men have the highest rates. However the summer peak did not occur leading the authors to wonder if suicide had simply been brought forward by the epidemic (16).

What of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19? Very little data on suicide are available but one US (17) and one Swedish study (18) using fairly reliable contemporaneous figures found no increase. It’s true, that there was a lot going on then! The Great War (like all wars) showed the expected drop in suicide, perhaps due to an increase in social cohesion, followed by an increase which coincided with Spanish flu, so teasing out the effects of each is impossible. As an aside, rates following the two world wars did rise again but not quite to pre-war levels and then peaked around the great depression. Rates in Europe and the UK have been gradually falling ever since. Indeed if there is a predictable harbinger of increased suicide on the large demographic scale it is economic hardship. It is therefore suicide rates over the next few years that will be most scrutinised.

There is no vaccine for suicide but there are some ways to increase immunity. Social proximity, economic support for those in poverty, agile and responsive mental health services, control of alcohol consumption being the most obvious.

One of my patients etched on my memory suffered depression severe enough to require in-patient care. He was driven to despair by religious guilt over a seemingly minor misdemeanour. As his mood improved with antidepressants and psychological support there seemed to be a glimmer of light, and he’d had enough of all that ‘religious nonsense’. I was reassured only for him to take his own life dramatically during a period of home leave a few weeks later (see 19). My lesson: whatever binds people together in society – shared values, beliefs, rituals – keeps us alive, regardless of their rationality.

In sum, when it comes to suicide, especially in the midst of a pandemic, it may be good to talk but it depends what you say. We might remember the WW2 safety slogan – “careless talk costs lives”. Perhaps the next mental health awareness campaign should be promoting the benefits of listening. Listening to what people are saying as well as what evidence and data are showing; we all need to try and learn from that.

And for every Werther there is a Papageno from the Magic Flute or George Bailey in ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ – numinous tales of people turning away from suicide thanks to others sharing ways to value continued living – despite moments of desperation. Don’t ever say it’s inevitable.

Professor Anthony David

Director, UCL Institute of Mental Health

References:

- Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapsychiatry/fullarticle/2764584

- World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: A resource for media professionals. 2017 https://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/resource_booklet_2017/en/.

- Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020. 7: 468–71. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32330430

- Hawton K, Marzano L, Fraser L, Hawley M, Harris E, Lainez Y. Reporting on suicidal behaviour and covid-19—need for caution. Lancet Psychiatry 2021. 8:15-7. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30484-3.

- Polihronis C, Cloutier P, Kaur J, Skinner R, Cappelli M. What’s the harm in asking? A systematic review and meta-analysis on the risks of asking about suicide-related behaviors and self-harm with quality appraisal, Archives of Suicide Research, 2020. DOI: 10.1080/13811118.2020.1793857

- Ortiz P, Khin E. Traditional and new media’s influence on suicidal behavior and contagion. Behaviour Science and Law. 2018. 36:245–256.

- Niedzwiedz C, Haw C, Hawton K, Platt S. The definition and epidemiology of clusters of suicidal behavior: a systematic review. Suicide Life Threatening Behavior.2014. 44, 569–581.

- John A, Pirkis A, Gunnell D, Appleby L, Morrissey J. Trends in suicide during the covid-19 pandemic: Prevention must be prioritised while we wait for a clearer picture. BMJ 2020;371:m4352

- Leske S, Kõlves K, Crompton D, Arensman E, Leo DD. Real-time suicide mortality data from police reports in Queensland, Australia, during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8: 58–63

- Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Tanaka T, Okamoto S. Nature: Human Behaviour. 2021. doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z

- National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health. Suicide in England since the COVID-19 pandemic- early figures from real-time surveillance. 2020. http://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=51861

- Qin P, Mehlum L. National observation of death by suicide in the first 3 months under COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2020.pmid: 33111325

- National Child Mortality Database. Child suicide rates during the covid-19 pandemic in England: real-time surveillance. 2020. https://www.ncmd.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/REF253-2020-NCMD-Summary-Report-on-Child-Suicide-July-2020.pdf

- Rogers JP et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020. 7: 611–27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32437679

- Chan SM et al. 2006. Elderly suicide and the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2006. 21: 113–18.

- Cheung YT, Chau PH, Yip PSF. A revisit on older adults suicides and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2008. 23: 1231–38

- Wasserman IM. The impact of epidemic, war, prohibition and media on suicide: United States, 1910–1920. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior 1992. 22: 240–54.

- Rück C, Mataix-Cols D, Malki K, Adler M, Flygare O, Runeson B, Sidorchuk A. Will the COVID-19 pandemic lead to a tsunami of suicides? A Swedish nationwide analysis of historical and 2020 data. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.10.20244699

- David A. Into the Abyss: a neuropsychiatrist’s notes on troubled lives. Oneworld Publications, 2020, London.

Applying for the UCL-Wellcome 4-year PhD Programme in Mental Health Science by Humma Andleeb

By iomh, on 6 November 2020

This is a series of blogs about my experience of the UCL-Wellcome Mental Health Science PhD programme. It will cover applying for the programme, the interview and lead up to enrolment stage of the programme as well as my experience of the programme and my PhD. I am publishing these blogs for prospective students in response to the queries I have received about the programme in response to my Twitter thread on successfully securing a place on the programme.

During my undergraduate degree in Biochemistry and Neuroscience, I worked with a PhD student on my research project and enjoyed it so much that I wanted to go on and do a PhD too. However, I was aware that the financial constraints and the commitment of doing a PhD were things to be carefully considered before taking the leap.

I applied for various research assistant posts with no success until I came across an opportunity with The McPin Foundation as a trainee researcher, with an emphasis on the importance of lived experience of mental health problems. In my teenage years, I experienced quite severe depression and self-harm and was regularly seeing a child psychiatrist in my local Child and Adolescent Mental Health service. This was the start of my journey in mental health research and what better way to get involved in research than by using my lived experience to inform the work. I was elated when, much to my relief, I got the position at McPin.

In my three years at McPin, I was able to work on qualitative studies as well as use my background in quantitative methods on projects. It is during this time that my passion for research in mental health was cemented and I knew doing a PhD was the dream next step in my career as a researcher. I say it was a dream because it really was. It is rare for South Asian women to pursue academia beyond undergraduate or Master’s studies. There is a pressure culture around preparedness for marriage, children and family. Although it is difficult to detach yourself from the guilt of not pursuing the path set out for you, it felt like a natural progression for me to further my experience and training in mental health research.

During my time working at McPin, I loved the social and psychological research but I was missing the clinical neuroscience aspect that I had become so interested in during my undergraduate studies. I had been contemplating PhDs for a while, browsing Find a PhD, and speaking to various academics in the networks I had built at McPin about funding opportunities and PhD projects, until I came across a tweet by Jon Roiser (the course director) on the news that the Wellcome Trust had awarded UCL a 4-year PhD programme in Mental Health Science!

The description caught my eye and upon exploring it further on the website, it seemed too good to be true. I was baffled as to how much it matched my interests, experiences and what I was looking for, all in one PhD. The main thing that stood out to me was the emphasis on collaboration and interdisciplinary research – a topic that I have often openly spoke about the need for in research, to better treat and prevent mental health problems.

I spent the following week exploring the application process and what the programme was looking for from applicants, as well as what it could offer me, before deciding to apply for it. For me, a major factor of pursuing a PhD was ensuring that I was an ideal candidate for the programme, but also that the programme met my needs and future aspirations. Having lived experience and using it to inform the research I have been and will be involved in, it was fundamental for me to be able to disclose that, and to ensure that there was adequate mental health support available during the course of a PhD.

As most will be aware, PhDs have the potential to be isolating for students due to the nature of working on a stand-alone project – therefore it’s crucial that students have appropriate support systems and networks around them. Having previous mental health problems may further exacerbate this isolation so the fact that the programme assigns each student an independent mentor as well as being part of a cohort of five other students on the same programme eased my worries.