Reflections from the first meeting of IoMH Special Interest Group in Psychological Trauma

By iomh, on 6 July 2022

This blog was written by UCL Division of Psychiatry PhD Student, Ava Mason.

The Institute of Mental Health (IoMH) Special Interest Group in Psychological Trauma is an interdisciplinary group of UCL researchers and clinicians from our partner NHS trusts. The meetings within this group aim to provide opportunities for collaboration between academics and clinicians, raise the visibility of trauma research at UCL and develop a UCL-wide ‘trauma strategy’. The first meeting included a range of hot topic talks, whereby each of the members discussed their research or clinical focus to the 150 attendees.

Dr Michael Bloomfield who chaired the event explained how one third of individuals who experience psychosis have also experienced previous childhood trauma. Reporting recent results from a large multi-site international study, he stated that 69.9% of participants who had experienced childhood trauma and had an at-risk mental state also had undiagnosed PTSD or complex PTSD. Relating to trauma experienced by children in care, Dr Rachel Hiller discussed key work currently being conducted investigating transdiagnostic predictors of mental health outcomes. This work could help to develop feasible and effective interventions and inform future service decision making for those in care.

The next hot topic was presented by Shirley McNicholas, who discussed multiple ways in which trauma informed care could be implemented, specifically referring to the women-only Drayton Park crisis house. She discussed how the environment can be used as a therapeutic tool to help people feel safe, while environment seen as punishing and criminalising negatively impacts women who require support. Trauma informed care also involves helping people connect the past to the present to intervene appropriately, reducing misdiagnosis, inappropriate care planning and compounding self-isolation and shame. A trauma informed organisational approach within Camden and Islington was then emphasised by Dr Philippa Greenfield.

She discussed the need to increase trauma informed culture embedded within all services and wider communities. This involves challenging inequality and addressing secondary trauma in the workforce and with patients and acknowledging the impact of adversity and inequality on physical and mental health. Currently, trauma informed collaborative and Hubs have been established to help manage change from within organisations and monthly trauma informed training is being run for staff, service users and carers.

Dr Jo Billings highlighted the considerable impact of occupational trauma within the workplace. Within the peak of the pandemic, this phenomenon had increased research focus, with studies finding 58% of workers meeting criteria for anxiety, depression, or PTSD. Within global research on police workers, 25.7% drank hazardously and 14.2% met criteria for PTSD. Focusing on UK research on 253 mental health professionals, high rates of burnout and secondary traumatic stress have been reported. Strategies that could mitigate this include increased reflective supervision, minimising work exposure where ethically possible and identifying individuals who may be at most risk.

Relating to plasticity enhanced psychotherapy, Dr Ravi Das discussed the importance of research aiming to improve synergy between drug and psychological treatments. Current medication for PTSD does not target causal mechanisms of PTSD, which may explain why many individuals with PTSD do not find medication effective. Drugs like Ketamine block NMDA receptors critical to memory formation and restores lost synaptic plasticity, preventing trauma memories from stabilising. This allows the memory and cognitions of the event to be altered during therapy. Future research should focus on specific medication that target mechanism of change itself to increase the effectiveness of PTSD treatments.

Dr Talya Greene discussed the impact of mass trauma, whereby the same event or a series of traumas affect many people at the same time. The current health system is not built to provide support to many individuals at once following an event, especially when the health workers themselves may be affected by the incident. Additionally, those that are affected by the event vary in many ways, from their cultural, mental health and trauma backgrounds to the way in which they were mentally or physically affected by the event itself. Focus is needed on the effects of early trauma responses on future health outcomes, and how to target groups that don’t normally access support due to physical difficulties or cultural background. Additionally, the current evidence base needs to be increased to see what may be effective specifically in the context of mass trauma settings.

Dr Mary Robertson and Dr Sue Farrier discussed various specialist services within Camden and Islington. One of these was the traumatic stress clinic, working with patients who have a history of complex trauma, including trafficking victims, war and conflict refugees, and individuals with a history of child abuse. The service helps to stabilise the individual before considering which trauma focused individual or group intervention to provide. Additionally, Operation Courage is the term used to describe several Veterans specialist mental health services. They offer comprehensive holistic assessment, referral to local services and in house social support, pharmacological and psychological treatment. These veteran services aim to offer quick support, working alongside statutory and non-statutory agencies where care is shaped by the service users. Alcohol and substance misuse is not seen as a barrier for treatment access, and services also provide peer support and consultation for carers and family.

The audience raised some relevant questions for the panel to discuss, such as how best to strengthen clinical and academic collaborations. Feedback suggested the need to quickly produce trauma informed digestible research that can be rapidly synthesised and relayed back to clinicians. The main barrier to this being a fundamental need for more funding to create a working relationship between academic and clinical services. Within under resourced clinical services, a network approach is required so clinicians can codevelop research questions with other colleagues and trainees to reduce research workload. The need to listen to the voice of marginalised groups within research was also discussed. This involves building a trusting relationship between researchers and BAME groups, to collaborate with service users and consider the impact of historical racism, family dynamics and cultural impact within trauma research. The panel also suggested ways to reduce occupational trauma through having a cohesive team where people can build resilience and support through integrating coping mechanism individually and as a team.

Lastly, Ana Antunes-Martins discussed the Institute of Mental Health Small Grants, providing funding for interdisciplinary teams of all mental health areas, prioritising applications focusing on mechanistic understanding of mental health.

The next meeting will focus more on some of the relevant points raised within this meeting, as well as potential collaboration opportunities. To find out more about this group (and future meeting dates) please visit: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/mental-health/special-interest-group-psychological-trauma

Close

Close

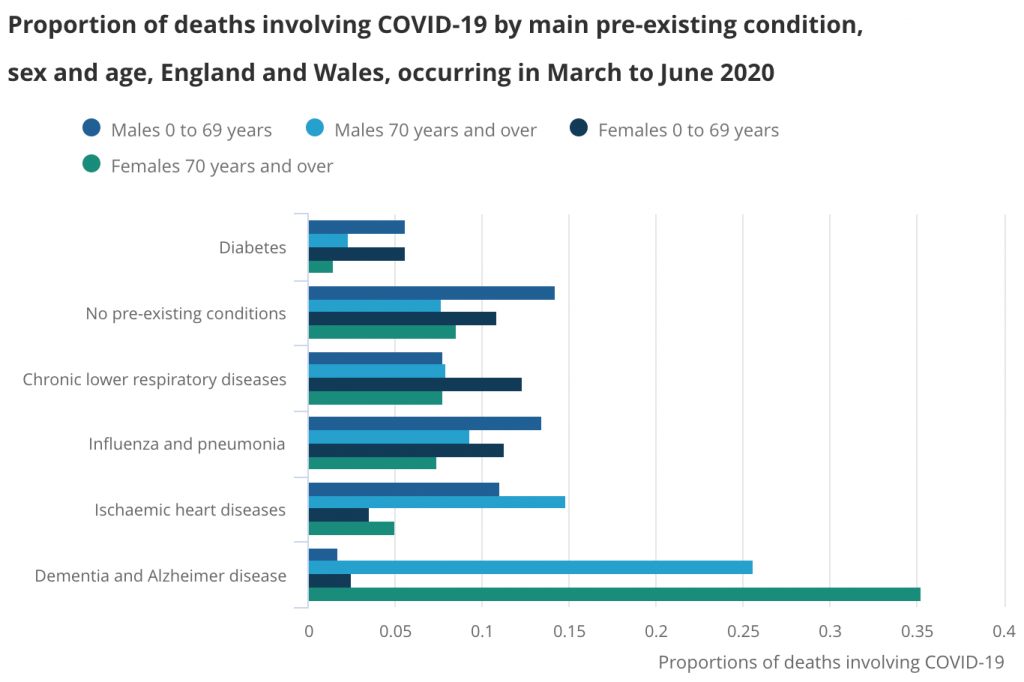

Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the most common main pre-existing health condition in deaths involving COVID-19 between March and June 2020. Published by the Office for National Statistics.

Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the most common main pre-existing health condition in deaths involving COVID-19 between March and June 2020. Published by the Office for National Statistics. Mental health hospitals experienced delayed access to PPE and COVID-19 tests during the first wave. Image by leo2014 from Pixabay.

Mental health hospitals experienced delayed access to PPE and COVID-19 tests during the first wave. Image by leo2014 from Pixabay. Staff working in older adult mental health services were concerned that some patients could not use the technology required for remote assessments. Image by Sabine van Erp from Pixabay.

Staff working in older adult mental health services were concerned that some patients could not use the technology required for remote assessments. Image by Sabine van Erp from Pixabay. The wellbeing of carers was often negatively affected by the pandemic. Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.

The wellbeing of carers was often negatively affected by the pandemic. Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay. Published by NHS England 2020

Published by NHS England 2020