The Department of Neuropsychology of the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery: response to the COVID-19 emergency

Jennifer A. Foley, Edgar Chan, Natasja Van Harskamp & Lisa Cipolotti

Department of Neuropsychology, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London.

At the time of writing, over 137,000 people worldwide have died with COVID-19 coronavirus. Since the first UK death less than one month ago, almost 13,000 people have now died, with numbers continuing to rise. The UK is in lockdown: ‘non-essential’ businesses and places of worship are closed. Similarly, schools are closed, except for children of key workers. People are only permitted to leave their houses for food, health reasons, one hour of exercise or essential work.

The COVID-19 emergency has required us all to rethink how we work. In the NHS we have had to restructure our clinical services. At the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (NHNN), a leading tertiary referral neuroscience specialist centre in the UK and part of University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (UCLH), two inpatient wards have been dedicated to COVID-19 patients. In response to the rising bed pressure at UCLH, the Hyper-Acute Stroke Unit has been transferred to the NHNN and a new ‘Emergency Stroke Unit’ created. As a consequence, the discharge of inpatients has been greatly expedited. To prevent the spread of COVID-19, the NHNN has been placed in lockdown; all visitors are prohibited, even for patients who are very sick and dying. Non-urgent outpatient clinics have been cancelled, with those remaining mostly provided by telephone. Outpatients deemed to be ‘extremely vulnerable’ by Public Health England have been advised to shield for 12 weeks and instructed not to leave their houses, even for shopping or medication.

Clinical staff has to work at a quicker pace, in longer shifts and in smaller teams because of increased staff sickness. They must provide more general medicine and have to learn how to use personal protective equipment (PPE). Academic staff has been redeployed clinically and some staff members have been redeployed to the new London NHS Nightingale Hospital. All staff have to work knowing that they might contract COVID-19, potentially placing themselves and their own household at risk.

In response to the COVID-19 emergency and the changes in clinical care at NHNN the Department of Neuropsychology reconsidered its priorities and how best to quickly respond to the new needs. We developed brand new services to support our staff, patients, and families and carers and took urgent action to provide top-class neuropsychological care. Here, we provide a description of how we have achieved this over the past two weeks.

The Department of Neuropsychology at NHNN

Neuropsychology is a highly specialised branch of clinical psychology, whose main focus is on addressing fundamental questions about the relationship between brain and mind. We investigate how changes in brain functioning caused by neurological disorder affect how we think and how we behave. Neuropsychologists are not only trained in general mental health, but also have additional qualifications and substantial specialist knowledge in the neurosciences.

The Department is one of the most renowned and prestigious in the world. Each year we treat approximately 6,700 patients. Our main clinical role is in the assessment, management and treatment of patients with complex neurological, neuropsychiatric and neurosurgical conditions. To meet this need, we have developed a flexible, adaptive and rapid neuropsychological assessment protocol, designed for speed of administration, reliability/validity, as well as detecting change from baseline. Our assessment comprises a brief clinical interview and formal evaluation of thinking skills, including general intelligence, memory, language, perception, frontal ‘executive’ functions and speed of information processing, in addition to assessment of mental health. These thinking skills are assessed with tests developed to be reliable, valid and graded in difficulty, and suitable for people of diverse backgrounds and abilities.

We have also developed a wide range of specialised treatment programmes. These mainly focus on group interventions to help patients cope with the neuropsychological sequelae of neurological conditions. We provide strategies to help reduce the impact of deficits of memory, planning, attention and other cognitive impairments on daily living. We also provide one-to-one support to mitigate anxiety and depression, and to support adjustment to the life changes precipitated by a variety of neurological conditions.

The Department plays a role in generating world-class clinical research, publishing approximately 40 peer-reviewed research papers each year. Our research strategy aims to improve diagnostic assessment and further the understanding of brain disorders and cognitive functioning. Recent focus has been on acquiring knowledge to help improve NHS neuropsychological service provision through: development of new tests to allow better identification of frontal executive and nonverbal memory impairments; development of new brief cognitive screening tools; and improved characterisation of the reliability and stability of neuropsychological tests over time, to allow objective monitoring of patients’ thinking skills. We also undertake research addressing questions regarding the neural architecture of cognitive domains, such as frontal executive functions, memory and language, and the characterisation of specific neurological conditions.

Support services for staff

The perceived availability of direct psychological support for staff is crucial for psychological wellbeing in times of crisis (e.g. Khalid et al., 2016). Hence, we have established a psychological support service for all staff. We have developed twice-weekly, face-to-face, walk-in clinics and daily telephone clinics. Our experience, so far, indicates that staff members greatly appreciate our support services. Despite the fact that our services started very recently, we have good intake that continues to increase.

Recent studies emerging from China specifically focusing on the COVID-19 emergency reported that overall there was little uptake of formalised psychological support (Chen et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). It remains unclear what type of support is most effective. Some studies have suggested that it is more helpful to focus on enabling staff members to meet their basic needs: health (adequate PPE), shelter (especially if having to isolate from family members), food and sleep (Chen et al., 2020; Khalid et al., 2016; Khee et al., 2004). Some of these studies have relatively little data (Chen et al., 2020), include few or closed questions (Dai et al., 2020), and/or non-anonymised data collection (Lee et al., 2005; Khee et al., 2004). These factors may somewhat limit the generalizability of their findings. Notably, no formal study has assessed staff members’ psychological needs during crisis in the UK. Therefore, we have developed an online survey to assess staff members’ distress and psychological needs, including access to basic provisions and usual coping strategies, as well as desire for informal or formal psychological support. The data will help us refine our support service response and inform future practice.

Neuropsychological services for inpatients

The Department has developed a highly specialised service to meet the demands of the increased number of acute stroke and neurosurgical inpatients within the time constraints of a very fast medical environment. We continue to provide comprehensive cognitive assessment where necessary, while also adopting a briefer specialist assessment model that draws upon previous work (e.g. Chan et al., 2019). In addition, we have developed a fast-turnaround reporting system to support early discharge and strengthened our work with multi-disciplinary teams to provide support for complex cognitive and behavioural difficulties. The quick discharge of patients with significant cognitive impairment has resulted in patients receiving only minimal rehabilitation in hospital. To support rehabilitation planning, we have focussed on building stronger links and outreaching to community services and relevant charity organizations such as Stroke Association.

Neuropsychological services for outpatients

Outpatient diagnostic services have been significantly delayed resulting in reduced care for patients with chronic and life-limiting neurological conditions. However, acknowledging that some assessments remain essential even during these times, we are continuing to provide face-to-face outpatient cognitive assessments for all urgent cases, with both clinicians and patients wearing PPE. We have deemed this to be necessary given the limited empirical evidence for either the validity or utility of diagnostic tele-neuropsychology (e.g. Bunnage et al., 2020).

For outpatients who have little social contact, isolation and delayed clinical care threatens to create a pandemic of loneliness (Armitage & Nellums, 2020; Van Bavel et al., In Press). The impact of this, exacerbated by increased exposure to negative framing within the media, will heighten stress responses. This may have a potential catastrophic impact upon mental health outcomes (Garfin et al., 2020). As far as we are aware, there are no evidence-based guidelines on how to manage patients’ distress at this time. Nonetheless, it is clear that patients need to be supported. Hence, we are offering all patients offered a rescheduled neuropsychological outpatient appointment a telephone consultation for interim psychological support. To relieve the burden upon already stretched clinical nurse specialists, GPs, community teams and voluntary sector helplines, we have also extended this service to all of the NHNN outpatients and stroke patients within North Central London.

Furthermore, those who had psychological difficulties before the current COVID-19 crisis are most vulnerable to exacerbated distress (Duan & Zhu, 2020). Therefore, we have not stopped any ongoing neuropsychological therapies and continue to accept all new routine referrals for ongoing psychological support. These appointments have now been converted to telephone clinics.

Support services for patients’ families and carers

For family members of inpatients with neurological conditions and/or COVID-19, we have started providing telephone consultations. For families and carers of stroke and neurosurgical patients, we have developed telephone psychoeducation about cognitive and emotional sequelae, and signposting for any ongoing needs.

Conclusion

In sum, we hope that our new support services not only contain and mitigate psychological distress, but also will allow us to research the psychological needs of staff, patients, their families and carers. By redesigning our existing neuropsychological services, we do not delay, but instead respond rapidly to the significant changes and increased demands caused by the COVID-19 emergency. These new services may be helpful in providing empirical evidence to determine which interventions are most useful. This will in turn inform future guidelines, should we have to face a resurgence of COVID-19 or another pandemic.

References

Armitage, R. & Nellums, L.B. (2020). COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly. The Lancet. Public Health; Mar 20.

Bunnage, M., Evans, J., Wright, I., Thomas, S., Vargha-Khadem, F., Poz, R., Wilson, C & Moore, P (2020). Division of Neuropsychology Professional Standards Unit Guidelines to colleagues on the use of Tele-neuropsychology. Division of Neuropsychology, British Psychological Society; Apr 20.

Chan, E., Garritsen, E., Altendorff, S., Turner, D., Simister, R., Werring, D. J., & Cipolotti, L. (2019). Additional Queen Square (QS) screening items improve the test accuracy of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) after acute stroke. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 407, 116442.

Chen, Q., Liang, M., Li, Y., Guo, J., Fei, D., Wang, L., He, L., Sheng, C., Cai, Y., Li, X. & Wang, J.(2020). Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7, e15-e16.

Dai, Y., Hu, G., Xiong, H., Qiu, H. & Yuan, X. (2020). Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on healthcare workers in China. medRxiv.

Duan, L. & Zhu, G. (2020). Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7, 300-302.

Garfin, D. R., Silver, R. C., & Holman, E. A. (2020). The novel coronavirus (COVID-2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure. Health Psychology; Mar 23.

Khalid, I., Khalid, T. J., Qabajah, M. R., Barnard, A. G. & Qushmaq, I. A. (2016). Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clinical Medicine & Research, 14, 7-14.

Khee, K. S., Lee, L. B., Chai, O. T., Loong, C. K., Ming, C. W., & Kheng, T. H. (2004). The psychological impact of SARS on health care providers. Critical Care and Shock, 100-106.

Lee, S. H., Juang, Y. Y., Su, Y. J., Lee, H. L., Lin, Y. H., & Chao, C. C. (2005). Facing SARS: psychological impacts on SARS team nurses and psychiatric services in a Taiwan general hospital. General Hospital Psychiatry, 27, 352-358.

Van Bavel, J. J., Boggio, P., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M., Crum, A., Douglas, K., Druckman, J., Drury, J. & Ellemers, N. (In Press). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behavior.

Zhu, Z., Xu, S., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Wu, J., Li, G., Miao, J., Zhang, C., Yang, Y., Sun, W. & Zhu, S. (2020). COVID-19 in Wuhan: Immediate Psychological Impact on 5062 Health Workers. medRxiv.

Close

Close

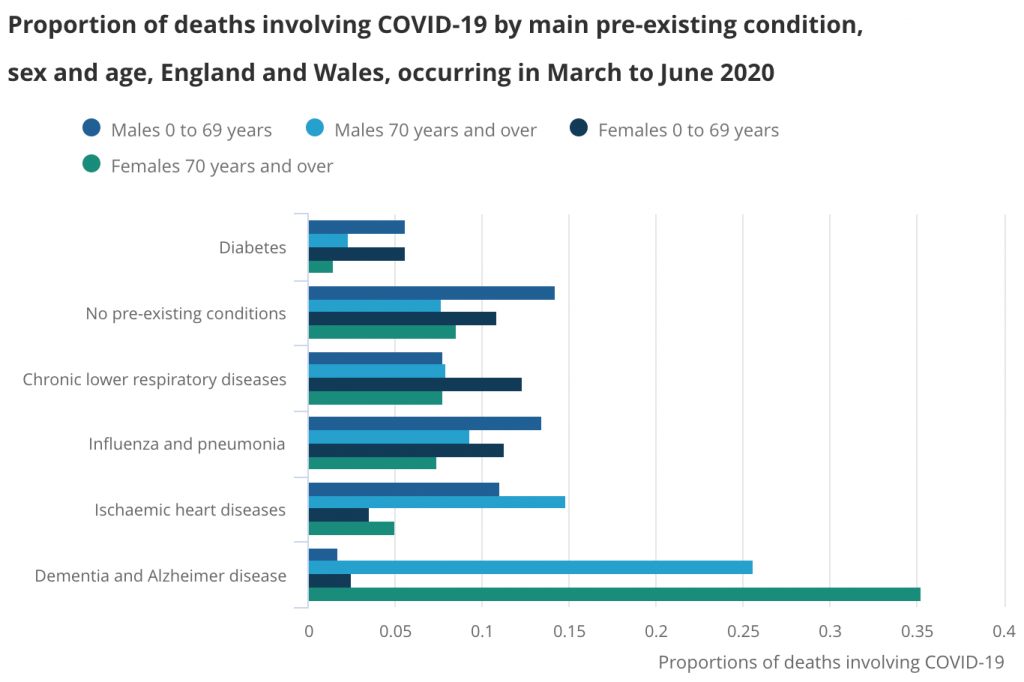

Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the most common main pre-existing health condition in deaths involving COVID-19 between March and June 2020. Published by the Office for National Statistics.

Dementia and Alzheimer disease was the most common main pre-existing health condition in deaths involving COVID-19 between March and June 2020. Published by the Office for National Statistics. Mental health hospitals experienced delayed access to PPE and COVID-19 tests during the first wave. Image by leo2014 from Pixabay.

Mental health hospitals experienced delayed access to PPE and COVID-19 tests during the first wave. Image by leo2014 from Pixabay. Staff working in older adult mental health services were concerned that some patients could not use the technology required for remote assessments. Image by Sabine van Erp from Pixabay.

Staff working in older adult mental health services were concerned that some patients could not use the technology required for remote assessments. Image by Sabine van Erp from Pixabay. The wellbeing of carers was often negatively affected by the pandemic. Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.

The wellbeing of carers was often negatively affected by the pandemic. Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay. Published by NHS England 2020

Published by NHS England 2020