Study Abroad in America – Northwestern University

By rmapapg, on 30 March 2017

Time flies fast. It is such a cliché, of course, but here I am, starting my third and last quarter at Northwestern, finding it hard to believe my third year of university spent abroad is going to finish so soon. The quarter system at NU, similar to the term system we have at UCL, definitely keeps everyone constantly busy and insensitive to the passing of time, with each quarter filled with homeworks, projects and exams.

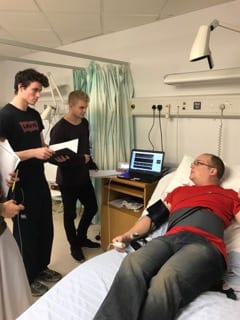

As an exchange student I am allowed to take any classes I like and the school itself is certainly an intellectually stimulating environment. I have really enjoyed this freedom of choice – I was able to do a lot of programming, an amazing mechatronics class, and a biomedical robotics class full of guest lectures from field experts working at Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago (RIC), the best rehabilitation hospital in the US, affiliated with Northwestern. My own design project this year involved cooperating with clinicians at RIC in order to develop a system for quantitative evaluation of Parkinson’s patients with the use of Kinect; some of the BME classes also take place there.

The BME department itself at NU is quite big and focuses not only on mechanical and electrical engineering but also on biological concepts such as regenerative engineering or drug transport. Students have a lot of flexibility in choosing classes and often do non-engineering ones as well, including literature or dance. And BME as a major is well respected – people here definitely know what it is (unlike often in the UK) and seem to be impressed whenever they hear about it because it is so broad in its science scope.

D espite a lot work, life can still be enjoyable! One of the things that make me most happy here is the amazing campus area, which is very spacious and green (I just can’t wait for spring!) and literally lies on L ake Michigan (not that many universities have their own sailing club and a dock). The main campus is located in Evanston, a northern suburb of Chicago, and the second one with RIC and the school of medicine is around an hour away in Chicago downtown. Because of this, most of the student life revolves around Evanston campus – the whole university experience is quite different from the one we have in central London. The campus life, along with university sports (which are taken very seriously!), is probably what really brings people together and gives this great sense of community and pride in the school one can feel at American universities.

espite a lot work, life can still be enjoyable! One of the things that make me most happy here is the amazing campus area, which is very spacious and green (I just can’t wait for spring!) and literally lies on L ake Michigan (not that many universities have their own sailing club and a dock). The main campus is located in Evanston, a northern suburb of Chicago, and the second one with RIC and the school of medicine is around an hour away in Chicago downtown. Because of this, most of the student life revolves around Evanston campus – the whole university experience is quite different from the one we have in central London. The campus life, along with university sports (which are taken very seriously!), is probably what really brings people together and gives this great sense of community and pride in the school one can feel at American universities.

Student life is quite different here and takes some time getting used to, but it does have its own perks. Sometimes I miss London with its big-city, hectic lifestyle, but at this point I think I will soon miss the American life too. Spring and summer will hopefully not make me fall in love with Chicago too much, as I have heard it does get really lovely here. For the time being, I am planning on not worrying too much and just enjoying these last warm months here to the fullest!

Student life is quite different here and takes some time getting used to, but it does have its own perks. Sometimes I miss London with its big-city, hectic lifestyle, but at this point I think I will soon miss the American life too. Spring and summer will hopefully not make me fall in love with Chicago too much, as I have heard it does get really lovely here. For the time being, I am planning on not worrying too much and just enjoying these last warm months here to the fullest!

Close

Close