“I took to going off for long tramps by myself over the fields and the beech-clad hills” – Frieda Le Pla, deaf-blind author

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 5 May 2017

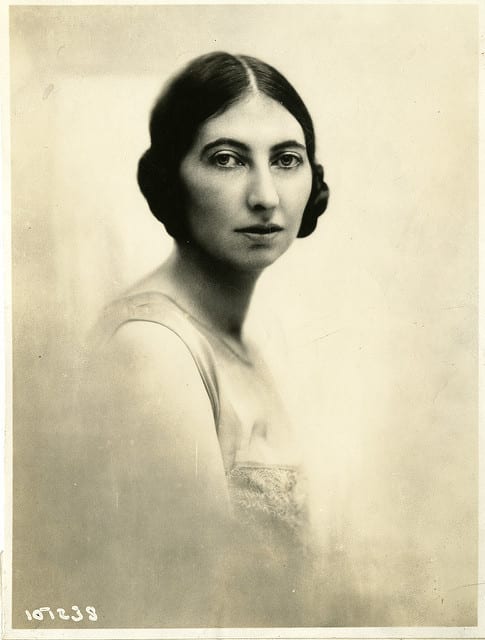

Frieda Le Pla, (or more correctly Winifred Jessie Le Pla) was born on November the 14th, 1892 in London (see Cripps, 1987, for most of what follows). Her Dublin born father, Matthew, was of Huguenot descent. He was a congregationalist minister. Her mother, who was his second wife, was born in Exeter of Scottish descent. When she was nearly nine the family moved from Amhurst Rd, Dalston, to Eynsford in Kent, and not long after they went to live in Ealing. In spring 1904 the family moved to Theale in Berkshire. There was, Cripps tells us, no suitable local school, so Winifred – Frieda – and her sisters Lillie and Rose were taught by her father in the mornings then were free to wander the local countryside for the remainder of the day. Her father was it seems rather forward thinking in his theology, and his support for controversial preachers meant that he lost his position, so the family moved again to Beckenham near Gainsborough for six months, then after only six months, they moved on to Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire.

Frieda Le Pla, (or more correctly Winifred Jessie Le Pla) was born on November the 14th, 1892 in London (see Cripps, 1987, for most of what follows). Her Dublin born father, Matthew, was of Huguenot descent. He was a congregationalist minister. Her mother, who was his second wife, was born in Exeter of Scottish descent. When she was nearly nine the family moved from Amhurst Rd, Dalston, to Eynsford in Kent, and not long after they went to live in Ealing. In spring 1904 the family moved to Theale in Berkshire. There was, Cripps tells us, no suitable local school, so Winifred – Frieda – and her sisters Lillie and Rose were taught by her father in the mornings then were free to wander the local countryside for the remainder of the day. Her father was it seems rather forward thinking in his theology, and his support for controversial preachers meant that he lost his position, so the family moved again to Beckenham near Gainsborough for six months, then after only six months, they moved on to Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire.

In her book about her experiences, Glimpses into a hidden world, which is not fully autobiographical but also discusses deaf-blindness more generally and also has contributions by others, Frieda said,

My first period of blindness came when I was about four years old, due to inflammation of the eyes; but it lasted only a few months, and I have no recollection of it myself. Neither did its effects – a greatly reduced amount of sight in the left eye, and short-sightedness in the right – obtrude themselves on my notice during my childhood, which in the main was a happy one […]. It was not until I was almost twenty-one that inflammation attacked the eyes for the second time, and that the first signs of deafness appeared.

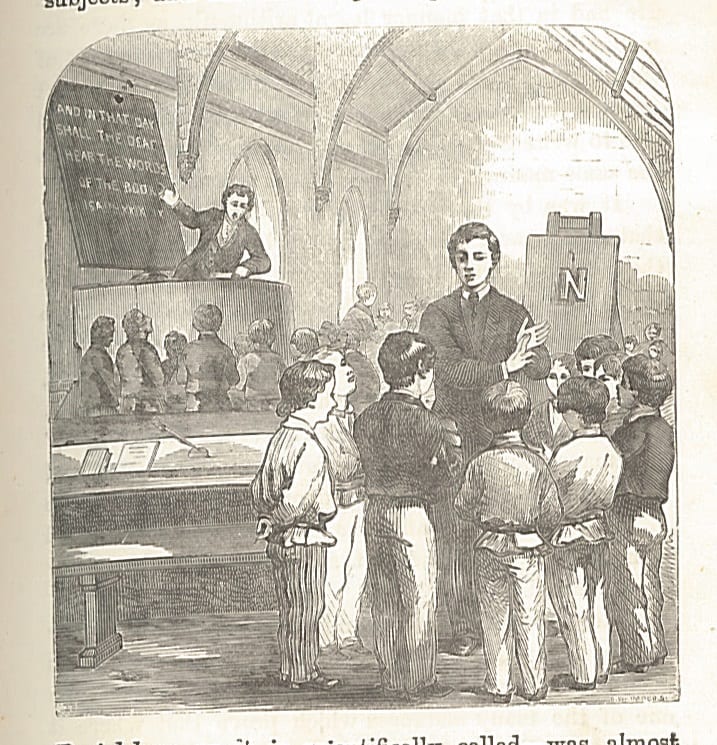

By this time I already had several pupils both for school subjects and music – I had started teaching music when I was sixteen: I was also a teacher in the Sunday-school, and was in the choir of the Beaconsfield Congregational Church, of which my father was Minister, and my mother the organist. I had also started to learn the organ, with my mother as teacher: and I was in the thick of enthusiastic activities for such movements as the Women’s Suffrage, the campaign against vivisection and other forms of cruelty to animals, and so on. This was in the autumn of 1913. (Glimpses into a hidden world, p.3)

By 1916 Frieda had to give up teaching, and by 1922 her blindness became ‘total’, although she was able to

see good print and also, of course, go about alone; so I took to going off for long tramps by myself over the fields and the beech-clad hills, with a note-book and a pencil in my pocket in order to jot down ideas for stories, and any notes about the wild folk and plants observed during these expeditions. The fluctuating character of my hearing made me nervous about meeting humans lest I should not be able to hear what they said if they spoke to me – another reason for preferring the more unfrequented woods and fields rather than the regions inhabited by humans.

Frieda set about learning Braille, and so was able to work as a writer. Her big problem was correcting manuscripts, and she tells us that even having had manuscripts checked, some errors still crept in.

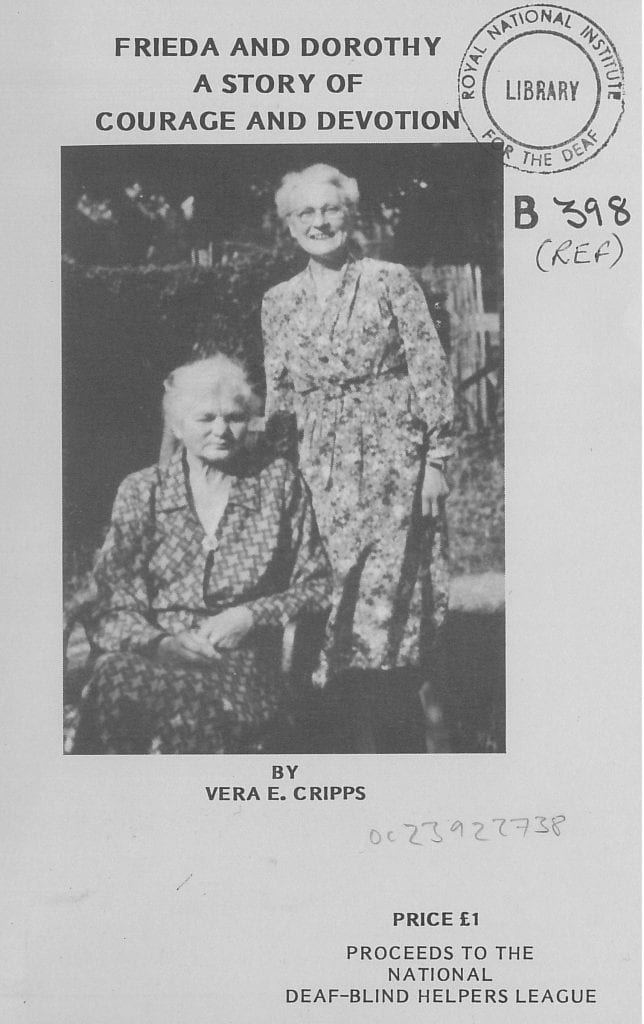

After her mother died in 1933, she was fortunate that a friend of hers, Dorothy Wells, a young teacher, became her companion in 1934. Dorothy had entered an Anglican convent but was not happy there, and seems to have welcomed the chance to help Frieda. She was to be her support and friend for the next forty-five years (Cripps, p.6).

Frieda died in March, 1978, after a short illness. Dorothy survived her, dying on the 15th of June, 1980. If you read through old copies on the British Deaf Times you will come across a number of her articles, particularly in the 1940s.

Frieda died in March, 1978, after a short illness. Dorothy survived her, dying on the 15th of June, 1980. If you read through old copies on the British Deaf Times you will come across a number of her articles, particularly in the 1940s.

Cripps, Vera E., Frieda and Dorothy, a Story of Courage and Devotion (1987)

Abrahams, Pat, Light out of Darkness, Hearing 1971, 26 137-9

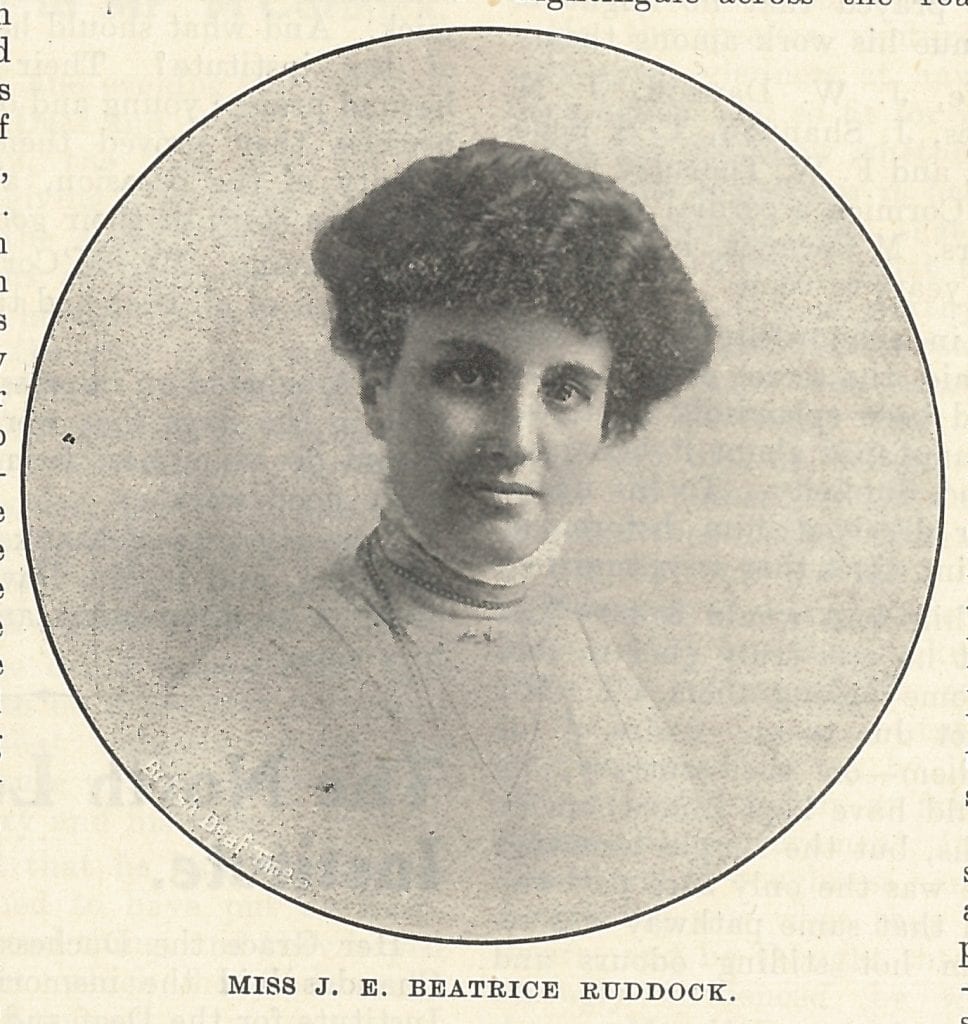

Deaf-blind authoress. British Deaf Times, 1932, Nov-Dec, p.127

Le Pla, Frieda, Glimpses into a hidden world, 1949.

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 216; Folio: 53; Page: 33

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 7811; Schedule Number: 152

Close

Close