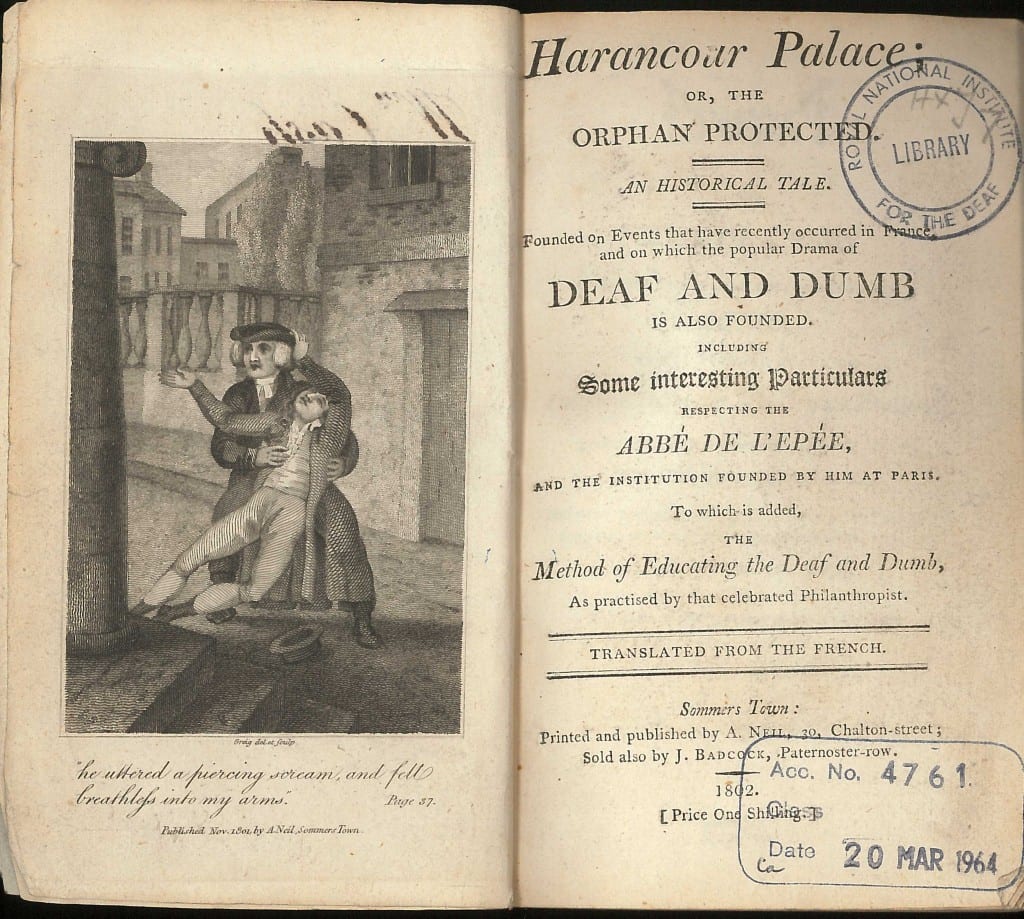

Harancour Palace; or the Orphan Protected

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 7 November 2014

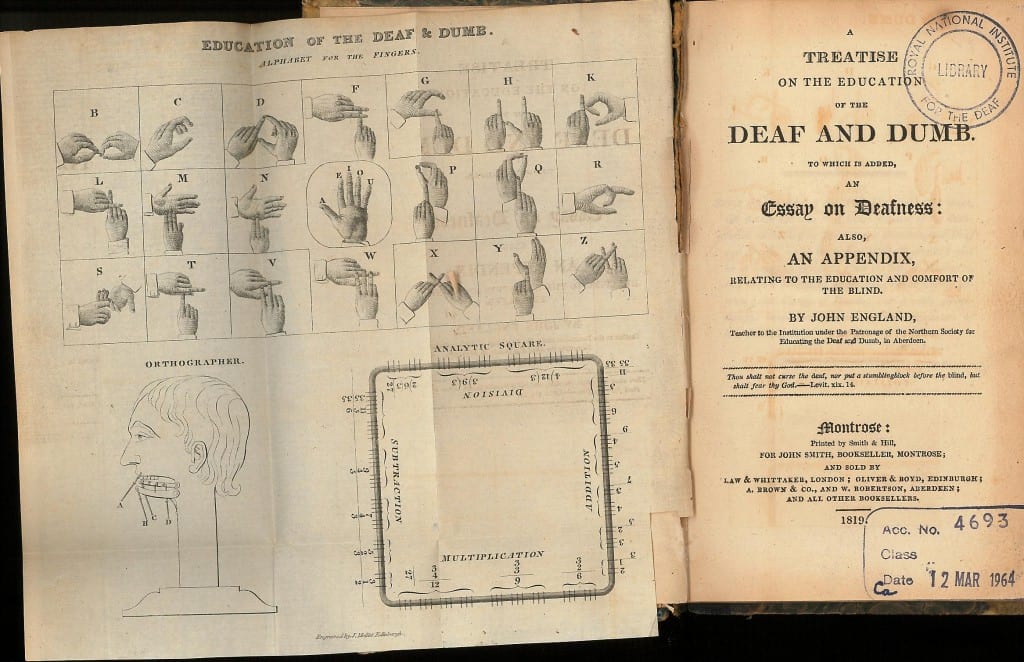

Harancour Palace; or the Orphan Protected is based on a play by the French writer Jean-Nicolas Bouilly (1763-1842), Deaf and dumb : or, The orphan protected. : an historical drama, in five acts. The story involves the Abbé de l’Epée who rescues the orphaned son of a French aristocrat, the Count de Sola, who has been rejected by his guardian, D’Arlemont. Everything ends happily as in all good melodramas, with the hero restored to his inheritance.

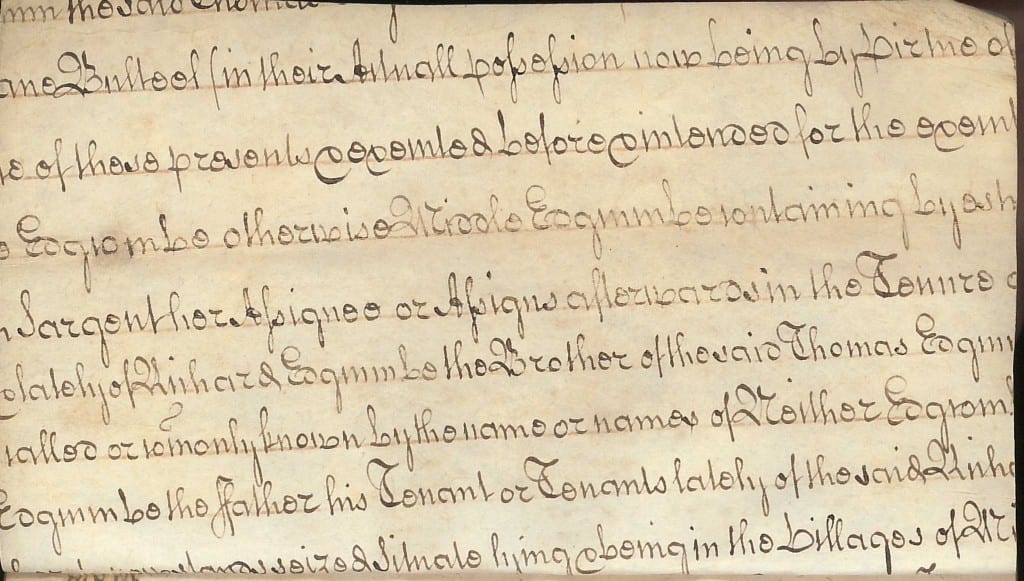

This book was published in 1802 as a prose version of the play, presumably cashing in on the success of the English version of the play, put on at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in 1801. Our copy has some of the pages misnumbered, for which no doubt some poor apprentice got a good beating, and that may explain why the binding is not hard but is parchment. Even more intriguingly, the inside of this parchment has an old legal document written on it, see below. This was not uncommon, as the bookbinders were careful not to waste valuable material. It seems to be a will, and you will note that no spaces are left between words so nothing can be added afterwards. I defer to those of you who are familiar with old hand writing to try to date it or read it – perhaps 18th century?

This book was published in 1802 as a prose version of the play, presumably cashing in on the success of the English version of the play, put on at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in 1801. Our copy has some of the pages misnumbered, for which no doubt some poor apprentice got a good beating, and that may explain why the binding is not hard but is parchment. Even more intriguingly, the inside of this parchment has an old legal document written on it, see below. This was not uncommon, as the bookbinders were careful not to waste valuable material. It seems to be a will, and you will note that no spaces are left between words so nothing can be added afterwards. I defer to those of you who are familiar with old hand writing to try to date it or read it – perhaps 18th century?

In 2011 Gallaudet produced a satirical play based on the Bouilly piece. Bouilly has another link with deafness – he was the author of the libretto that formed the basis of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio.

Note: I had missed an obvious typo in the title and put Harancour Place instead of Palace! Apologies for my sloppiness…

I have now added the complete document – note that the printer confused the pagination quite a bit. PDFsam_Harancour

Close

Close