“Dummy” the deaf so-called ‘witch’ of Sible Hedingham

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 2 August 2019

The village of Sible Hedingham was once known as the birthplace of the condottiero Sir John Hawkwood, but after a trial in 1864, it became known for an assault on a deaf ‘witch’ who shortly after died of his injuries. It is therefore one of the last ‘witchcraft’ cases in Britain.

We do not know the name of the deaf man – he was locally, unimaginatively, called ‘Dummy’ (circa 1780-1863), but his real name is unknown and possibly now unknowable. He was supposedly from France, and had lived in mud hovel locally for seven or eight years. Before that, some newspapers reported that he was in Braintree. Locally it seems he was known as someone people went to for ‘divination’ or fortune telling, and from papers gathered in his hut by the police, we can recognize the syntax and sounds of Essex dialect –

“Her husband have left her manny years and she want to know weather he is dead or alive.” “What was the reeson my sun do not right ? i meen that solger.” “Do you charge any more ?” The answer to this question was doubtless satisfactory, for this momentous question was then put: “Shall I ever marry ?” Love letters from girls to their sweethearts were also found with “Shall I marry ?” and “How many children shall I have ?” written in pencil on them. The most business-like of all the notes was the next one, “Did you say we kild your dog ? If you do I will send for the policeman.” Nor were his patrons altogether confined to the lower orders. One letter states that the lady was “comen herself on Mundy to see yoo, and she gave you oll them things and the shillin.” In the hovel were found, besides between 400 and 500 walking sticks, a quantity of umbrellas, some French books, a number of tin boxes, some foreign coins, chiefly of the. French Empire, and about a ton of rubbish which it was found impossible to classify in the inventory that was taken. The most definite ideas about the man have been suggested by the following questions which were found written seriatim on a scrap of paper. “Were you born at Paris ?” “The name of the town where you were born ?” “When was your tongue cut out ?” “Le nom de votre ville ?” The answers were no doubt made by signs. (Times of September 24th, 1863)

This shows how widespread folk beliefs were in the late 19th century, in an area that was infamous for Matthew Hopkins and witchcraft trials in previous centuries.

This shows how widespread folk beliefs were in the late 19th century, in an area that was infamous for Matthew Hopkins and witchcraft trials in previous centuries.

Emma Smith, thirty-six, and Samuel Stammers, twenty-eight, were taken to court for leading a mob in an assault on the poor old man, which led to his death the next day. The old man was accustomed to visit

the village of Ridgewell, a few miles distant from Hedingham, and there made the acquaintance of the prisoner Smith, at the beer-house of her husband. It seems that on the occasion of one of these visits to Ridgewell, the poor old man wanted to sleep at the prisoner’s house, and on her refusing to allow him to do so, he stroked his walking-stick, and used other threatening signs to her as signifying his displeasure at her refusal; and although he could neither hear nor speak he had no difficulty in understanding and making himself understood, and some of these signs accompanied by violent gestures were looked upon with considerable awe. Soon after this expression of the old man’s displeasure, the prisoner Emma Smith became ill and disordered, and was reduced to a low, nervous condition, and at once expressed her conviction that she had been bewitched by old Dummey, and that she would never recover till she had induced him to remove the spell from her, and made several applications to him for that purpose, as it would seem, without effect. At last, and while labouring under great mental and nervous excitement she went from her home at Ridgewell to Sible Hedingharn on the evening of the 3rd of August, 1863, and met old Dummey at the Swan public house, which is situated about a quarter of a mile from Dummey’s hut. They remained there together for some hours, she endeavouring to persuade him to go to Ridgewell with her and sleep in her house, and offering him three sovereigns to do so. Dummey, however, refused to go, and drew his fingers across his throat, implying that he was afraid of having his throat cut. As soon as it became known in the town that a woman from Ridgewell, who had been bewitched by old Dummey, was at the Swan, a great number of villagers flocked to see her, and the Swan soon became a scene of riot and confusion, and the old man was pulled and danced about, falling once or twice violently to the ground. The prisoner Smith still continued to urge the old man to go home with her, repeating that she would give him three sovereigns, and would treat him well, and that she had been in a bad state for nine or ten months, and that she was bewitched. After the closing of the Swan the parties adjourned outside, and the prisoner Smith was seen standing by the side of Dummey, declaring that he should go home with her. She then tore the old man’s coat, struck him several times over the arms and shoulders with his stick, and kicked him and dragged him down to a little brook which runs across the road, and down a lane near the Swan; and was proved to have said to him, “You old devil, you served me out, and now I’ll serve you out.” Smith then shoved him into the brook, and when he was getting out the other side she went round over a little bridge, and the other prisoner, Stammers, went through the brook, and they both pushed him back into the brook. (Reynolds’s Newspaper – Sunday 13 March 1864)

The old man was found the next day in his hut by Mr. Fowke, a local Poor Law guardian, shivering in his wet clothes. “The post mortem examination showed that the lungs and kidneys were much disorganized, the pericardium adhering to the heart, and a “suffusion of lymph on the membrane of the brain, indicating recent inflammatory action, and the witness gave it as his opinion that he died from the disease of the kidneys, produced by the immersion in the water, and the sleeping in his wet clothes, and in this opinion the witness was corroborated by another medical man who attended the post mortem examination.” (Reynolds’s Newspaper – Sunday 13 March 1864)

At the March Assizes at Chelmsford, the two were found guilty of manslaughter, and sentenced by Lord Chief Justice Earl to six months’ imprisonment. Samuel Stammers presumably lost his business – he had employed 4 people as a builder, according to the 1861 census, and though he had a daughter in 1868, she died that same year. He himself lived only until 1869. Emma Smith, I have not found, so I do not know what happened to her. The whole sorry tale illustrates how ignorant people can be with regard to those who they cannot understand.

Some in the village were thoroughly appalled that their name was besmirched by a mob. In the Essex Standard, for Friday 25th March, 1864, there is a letter that was sent to the Times by the Rector –

I hope that in justice to myself and other residents within the parish of Sible Hedingham, you will kindly insert a few remarks with reference to the case of man-slaughter tried at the last Chelmsford Assizes, and reported in the columns of your widely-circulated journal. Too much commendation cannot possibly be bestowed on Mr. Fowke for the pains which he has taken in bringing to punishment the perpetrators of so wanton an attack upon a poor and afflicted old man ; but, at the same time, it would be most unfair that an impression (certainly erroneous) should get abroad that there were not many other persons in the parish who regarded with horror and detestation the gross outrage committed on the night of the 3rd of August. I therefore feel called upon to assure the public, through the columns of your newspaper, that a subscription will be entered into among the parishioners whereby the expenses of this trial will be defrayed. Furthermore, perhaps I shall be only justified in adding that as soon as I had learnt of the treatment which the poor old man had received I hastened to the spot, that I spent the greater part of the afternoon in administering to him consolation, that I went myself to the surgeon to see whether I should be justified in having the sufferer removed to the Union, that I then procured the cart for him and saw him placed in it, and, moreover, that, with the assistance of the superintendent of police, I went to every house in the village where I thought I might gain sufficient information to lead to a warrant being issued against the aggressors in this most disgraceful affair. As Mr. Fowke had heard of the attack early in the morning and had been with the poor old man previously to my arrival, and, like a good Samaritan, administered comfort to him ; and as he had, moreover, in the capacity of guardian, sent for the superintendent of police, we thought it advisable, after due consideration, that the summons should be issued in bis name; but at the same time there is scarcely a man in the parish who will not, I believe, readily come forward to prevent the burden of the expense falling upon his shoulders. May I add one word more? In spite of the stigma which has been cast on the parish of Sible Hedingham from the publication of so unfortunate a catastrophe, I fearlessly challenge any person unprejudiced and capable of judging to visit the poor in their cottages, to inspect the schools within the place, and to observe the general tone of the parish, and I do not hesitate for a moment to pronounce an opinion that such a person will arrive at the conclusion that, in regard to intelligence, civility, and general good conduct, the much-maligned inhabitants of Sible Hedingham are considerably above, rather than below, the average. During the eight years that poor old ‘ Dummy ‘ resided in this place he was treated with the greatest kindness, both by the rich and the poor, and nothing ever occurred to cause the slightest apprehension that his end would have been so tragical.

Punch had this satirical poem, printed again in the Brecon Reporter and South Wales General Advertiser for Saturday 10th October, 1863 –

The Serfs of Castle Hedingham.

Ye wives of Castle Hedingham, ye matrons, and maids,

Who follow in such thorough style the wizard finder’s trades;

Your shud’ring countrymen all in tones of loathing say,

The fiends of Castle Hedingham, how horrible are they!Just like the savage feminines who own Dahomey’s rule,

They show the wild oat fierceness of the Charlotte Corday school;

With hearts that scorn the softness that should female impulse sway,

The fiends of Castle Hedingham, how horrible are they!Ye men of Castle Hedingham, and ye that represent (?)

The stain on England’s franchise list in British Parliament;

What say you, Major Beresford, of this most Tory trait,

The serfs of Castle Hedingham, how ignorant are they!Saint Stephen’s could well spare you, and you’d for once of use,

If leaving Tory platitudes, you’d study to produce

A landlord who, Conservative, could yet unblushing say,

The tenantry of Hedingham, how well informed are they!

Presumably he was buried in a pauper’s grave.

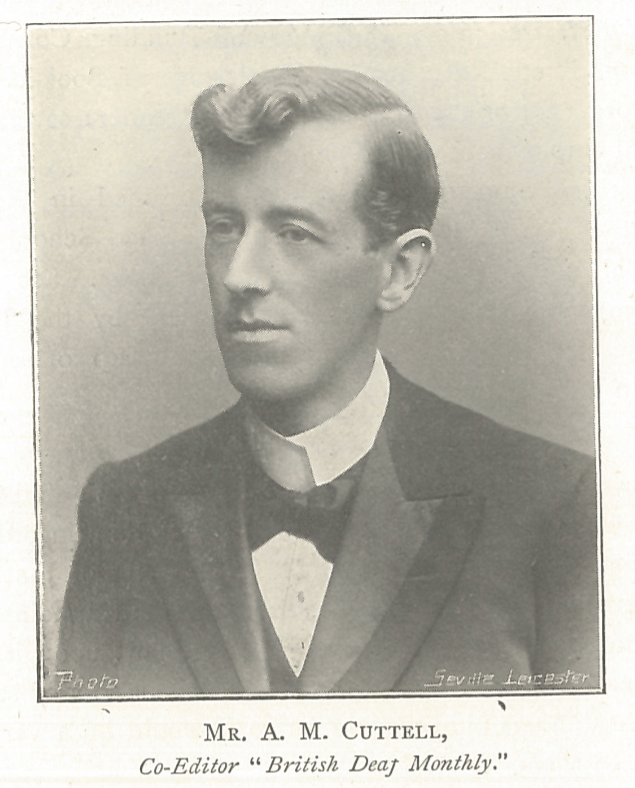

[Note – the captions to the photos in Oxley’s hand, he had the wrong information and wrong date.]

Deaths Dec 1863 Unknown, Dummy, Halstead 4a 216

Wilts and Gloucestershire Standard – Saturday 26 September 1863 p.4

Close

Close