In our collection we have a big thick green-bound ledger, measuring approximately 13 1/4″ by 8 3/4″. A torn bit of paper on the front cover indicates that it was used by the Poolemead Home for Deaf Women, at 9 and 10 Walcot Parade, Bath, to record names and details of the inmates.

The home, founded in 1868, became known as the Deaf and Dumb Industrial Home, then was taken over by the National Institute for the Deaf in 1932, and moved to ‘Poolemead’ at Twerton-on-Avon, near Bath, in 1933, and is now known as the Leopold Muller Deaf Home.

The home, founded in 1868, became known as the Deaf and Dumb Industrial Home, then was taken over by the National Institute for the Deaf in 1932, and moved to ‘Poolemead’ at Twerton-on-Avon, near Bath, in 1933, and is now known as the Leopold Muller Deaf Home.

The Story of how the home began is related in Silent World (1946) –

An old four-page pamphlet, grubbed up from the archives of 105 Gower Street, and believed to be the only copy in existence, told me all there was to know about the beginning s of what we now call “Poolemead”. How the Reverend Fountain Elwin, of Temple Church, Bristol, found a little deaf mute girl in his parish and took her into his home; of how the family moved to Bath; and how his daughter and her friend Miss White went about the city looking for deaf and dumb children, found several neglected little waif, and began to teach them in a rented room in Orange Grove.

A Hundred Years Ago

This must have been about 1832, for our pamphlet tells us that Miss Elwin began her life’s work among the deaf when she was eighteen, and she was born in 1814. she died when she was ninety.

Her early efforts went so well and aroused so much interest that in 1840 a Committee was formed and premises taken over at 9 Walcot Parade. In 1868 a home for adults was started, and by the middle 1890’s the adult work had far outstripped the school. The State was beginning to accept its proper duty of educating the young, and by 1897 the school had been closed altogether and the Charity Commissioners had agreed to the accumulated funds and property being used entirely for the home.

So the Bath Home for Deaf and Dumb Women came properly into being.

What became of the leaflet I cannot say – it is possible it survives in the collection hidden somewhere. We have very little for Bristol in general (two late 19th century reports from the Bristol Institute are ‘missing’) and nothing from Bath, so I cannot compare anything in the way of annual reports for the home. The founder was Jane Elwin, Fountain Elwin’s daughter. Initially I connected him with the Elwin family in Norfolk, who produced another Fountain Elwin around the same time, but census returns show he was born in Middlesex circa 1784. I believe that they may well have been related. Elwin was ordained in 1810 and ended up at Bristol’s large (now ruined) Temple Church. He died in Bath in 1869 aged 85. Jane was born in Bedminster, dying in 1904. The 1901 census describes her as having ‘senile decay’.

The 1851 census shows a seventeen year old house maid, Elizabeth Buck, who was ‘deaf and dumb’ – surely this might be the deaf girl taken in by Elwin? She was not described as deaf on the 1841 census.

If I discover anything more about Jane Elwin and Bath I will update this page.

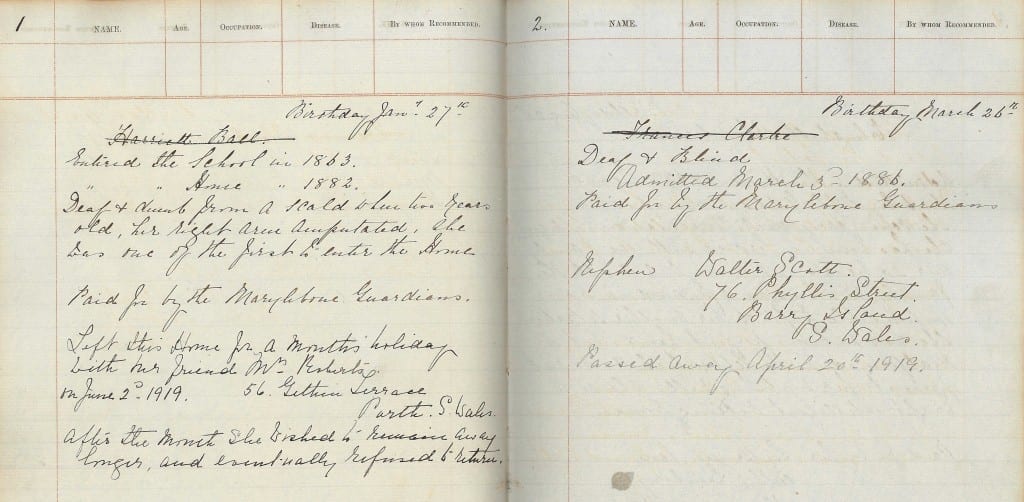

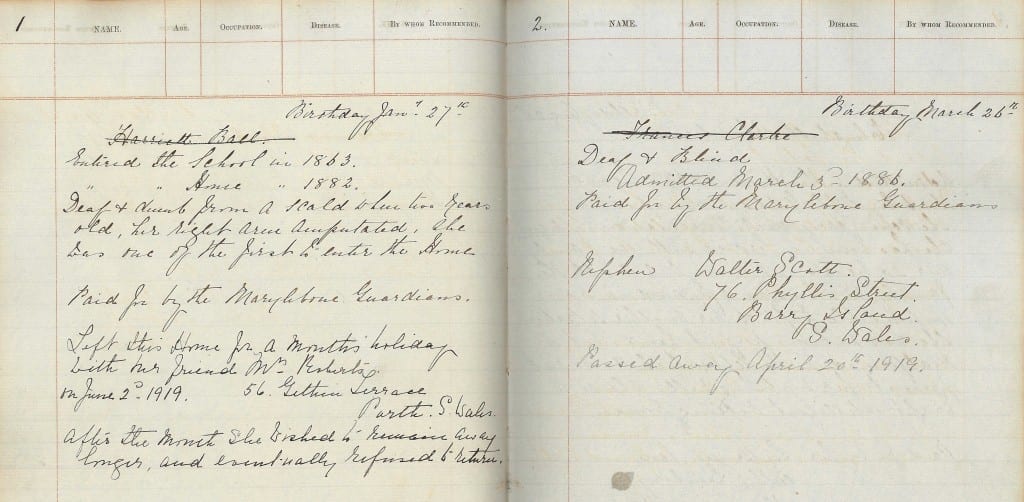

The ledger illuminates other information we can find on the census (and no doubt other records). For example, the first person listed for the Bath home is Harriet Ball – see below on the left (click to enlarge). She was “deaf and dumb from a scald when two years old, her right arm amputated, she was one of the first to enter the home”. An audiologist I consulted suggests that she may have had non-organic hearing loss, but it is far more likely that she had hearing loss that had not previously been detected. The Bath Home seems to have used the ledger into the 1930s, though with only basic information on the later entries.

Prior to its use by the Bath Home, the ledger started life in Norwich as we can see from the plate in the inside front cover here.

Prior to its use by the Bath Home, the ledger started life in Norwich as we can see from the plate in the inside front cover here.

Now look again at the front plate at the top of the page and underneath the label we can make out the words ‘Homeopathic Hospital’. It was originally used then by one of two possible homeopathic hospitals in Norwich at that time, the first entry being for a Susan Bush in 1856, the last in 1860 by …son (name partly concealed). Here is an example of a patient in 1856, and I have chosen one who was deaf – Eliza Landamore. Click for a larger size.

Now look again at the front plate at the top of the page and underneath the label we can make out the words ‘Homeopathic Hospital’. It was originally used then by one of two possible homeopathic hospitals in Norwich at that time, the first entry being for a Susan Bush in 1856, the last in 1860 by …son (name partly concealed). Here is an example of a patient in 1856, and I have chosen one who was deaf – Eliza Landamore. Click for a larger size.

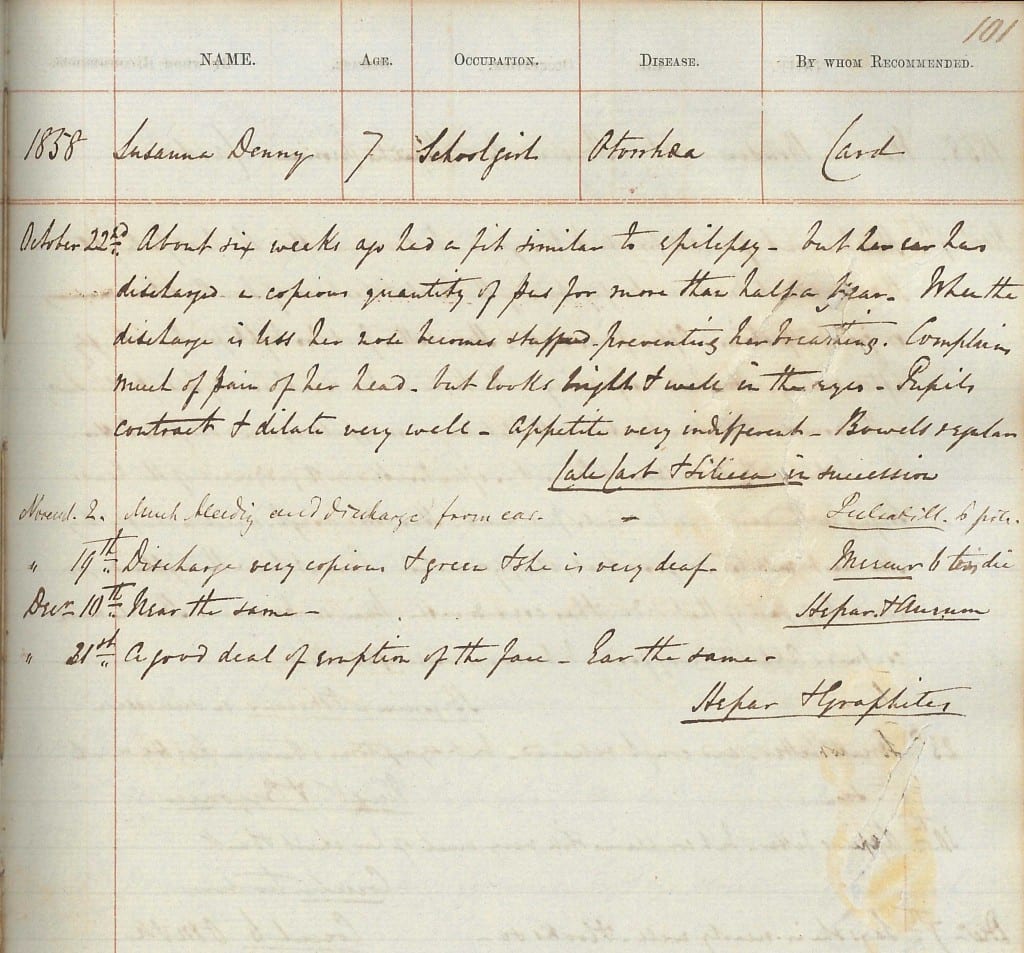

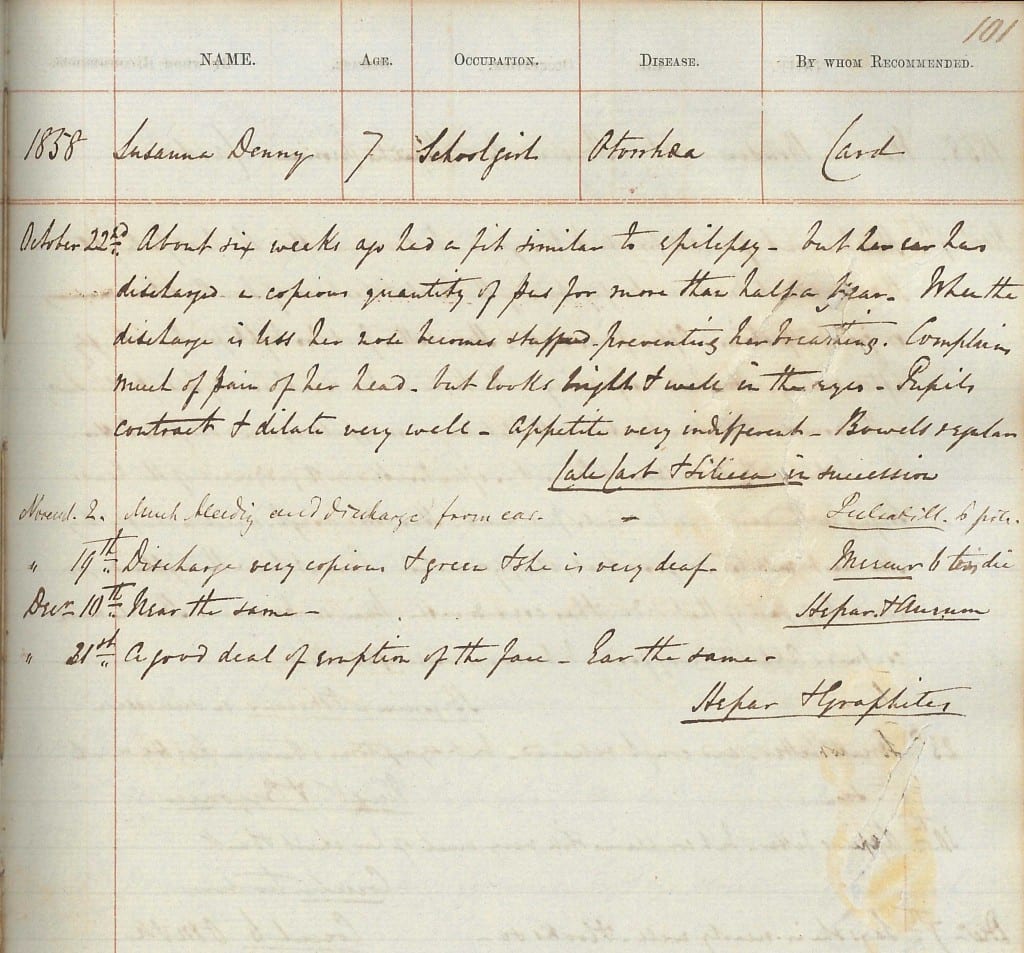

A second example is below – and again I chose a person with a hearing problem, Susanna Denny who has ‘ottorhea’.

A second example is below – and again I chose a person with a hearing problem, Susanna Denny who has ‘ottorhea’.

Another patient, Robert Rippingale, born in 1843 in Catton (near Norwich)

Septr. 9th 1856 “For the last six years has had scrofulous swellings of the neck [from?] the remains of an old sore. Perfectly adherent to the bone of the lower jaw. His general health has been tolerably good. Has been an outpatient of the Norwich Hospital but without benefit.

Silica [6?]

16th Rather better ”

23rd Still improving Sulph + Silica

Robert did not live long – sadly he died in 1864.

At some point in 1860 I would surmise, the ledger met with an unfortunate accident. Having read the heading of the article I think you will know where I am going with this… Someone spilt urine onto the ledger, sticking many pages together. Sadly some idiot later attempted to part the pages, damaging many. It still smells very strongly of the cause of this accident! However, clearly, as it was only partly used someone decided that it still had plenty of life left in it. Quite how it travelled from Norwich to Bath we can only guess, but as you read above there was some sort of a possible connection with the Elwin family of Bath and Elwins in Norwich (a Robert Fountain Elwin was a rector in Norfolk).

If anyone recognises the hand that the Norwich part of the record was written in, please let us know. There is no name in the front, so I cannot be sure who first used the book. The Bath part was probably written by Emily Walker Morgan, head of the home in 1911 (aged 45) where the handwriting matches that at the start of the Bath part of the ledger. I surmise it was first used by her around 1910.

Later enties show the handwriting getting shakier into the 1930s before it changes, and the record is less detailed.

Silent World, 1946, October, p.112-4

1841 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 970; Book: 3; Civil Parish: Walcot; County: Somerset; Enumeration District: 5; Folio: 7; Page: 6; Line: 20; GSU roll: 474610 (for the Elwins)

1841 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 931; Book: 13; Civil Parish: Lyncombe and Widcombe; County: Somerset; Enumeration District: 4; Folio: 27; Page: 5; Line: 18; GSU roll: 474593 (for Elizabeth Buck)

1851 Census – Class: HO107; Piece: 1943; Folio: 464; Page: 32; GSU roll: 221102

1861 Census – Class: RG 9; Piece: 1690; Folio: 53; Page: 6; GSU roll: 542851

1871 Census – Class: RG10; Piece: 2487; Folio: 55; Page: 5; GSU roll: 835196

1881 Census – Class: RG11; Piece: 2438; Folio: 30; Page: 4; GSU roll: 1341587

1891 Census – Class: RG12; Piece: 1935; Folio: 53; Page: 7; GSU roll: 6097045

1901 Census – Class: RG13; Piece: 2341; Folio: 19; Page: 4

1911 Census – Class: RG14; Piece: 14715; Schedule Number: 333

Emily Walker Morgan Head 1866 45 Female Single Head Matron Of Institution Dublin 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Elizabeth Martin Assistant 1868 43 Female Widowed Assistant Matron Bath, Somerset 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Harriett Ball 1857 54 Female Single Paddington, London, England 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Frances Clark 1846 65 Female Single Paddington, London, England 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Elizabeth Chambers 1848 63 Female Single Liverpool, Lancashire 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Ann Rogers 1850 61 Female Single Bridgend, Glamorganshire 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Louisa Tickett 1857 54 Female Single Mile End, London, England 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Elizabeth Townson 1882 29 Female Single Liverpool, Lancashire 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Ellen Hillyer 1857 54 Female Single Dorchester, Dorset 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Ann Adams 1857 54 Female Single Milton Nr Lymmington, Hampshire 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Eliza Curl 1875 36 Female Single Dereham, Norfolk 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Emily Hubbard 1864 47 Female Single West Ham, London, England 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Honor Ninnes 1886 25 Female Single St Ives, Cornwall 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Elizabeth White 1846 65 Female Single Devizes, Somerset 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Charlotte Lowndes 1871 40 Female Single Brighton, Sussex 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Annie Shepherd 1872 39 Female Single Leeds, Yorkshire 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Georgina Fuller 1850 61 Female Single Norwood, Surrey 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Ellen Smith 1888 23 Female Single Paddington, London, England 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Annie Crouch 1873 38 Female Single Hammersmith, London, England 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

Alice Turner 1872 39 Female Single Eastbourne, Kent 10 Walcot Parade, Bath

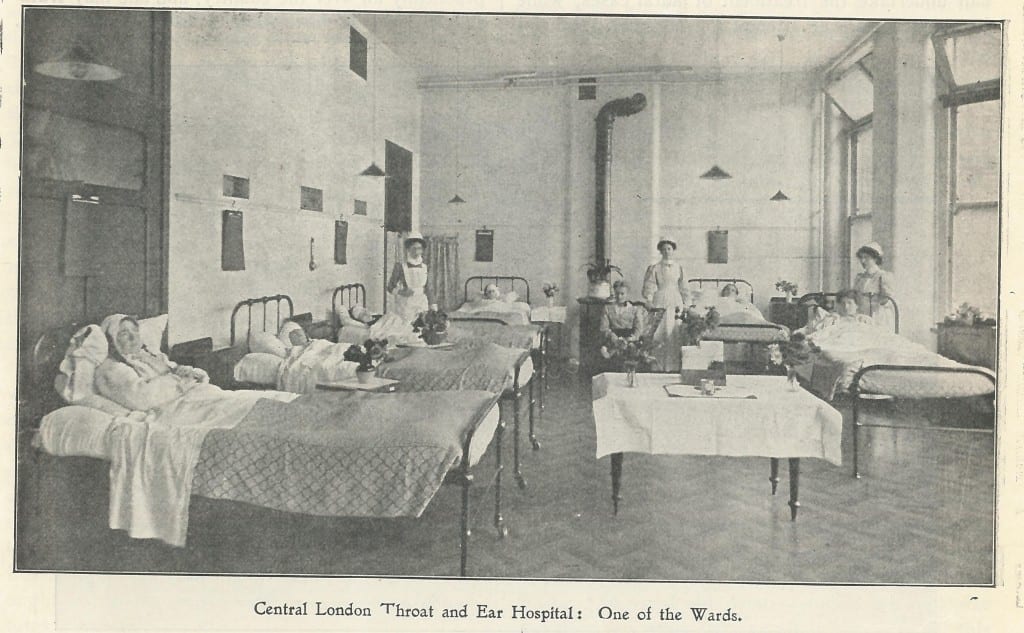

The last view appears to be looking east. Compare this shot taken from the library window – it is not easy to be sure as some buildings have of course gone and others have been built. See the Lost Hospitals website for some of the older buildings that were or are part of this hospital. Click on images for larger size.

The last view appears to be looking east. Compare this shot taken from the library window – it is not easy to be sure as some buildings have of course gone and others have been built. See the Lost Hospitals website for some of the older buildings that were or are part of this hospital. Click on images for larger size. Close

Close