“Mr. Greaterick stroked him again, rubbed his Body all over with Spittle” – An account of Mr. Greaterick and his Miraculous Cures.

By H Dominic W Stiles, on 25 September 2015

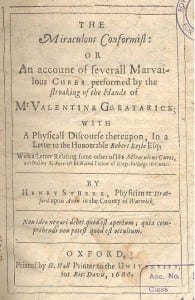

Lincolnshire born Henry Stubbe or Stubbes (1632-76) grew up in Ireland after his ‘anabaptistically inclined’ father was expelled from his living as Rector of Partney. His mother took him to London in 1641 after the rising, and he attended Westminster School where he excelled at languages. The OED entry says “Stubbe’s sharp tongue and conceit often caused him to be ‘kick’d and beaten’ by his fellow students and, on one occasion at least, publicly whipped in the college’s refectory ” (ODNB). After his BA and then serving in the Parliamentary army for two years, Stubbes returned to Oxford and was was appointed deputy keeper of the Bodleian Library (ibid). Around this time he became friends with various luminaries of the time including Thomas Hobbes and Thomas Willis, a founder member of the Royal Society. After studying medicine and writing The Indian Nectar, or, A Discourse Concerning Chocolata (1662), he eventually settled in Warwickshire. It was there that he came across Valentine Greaterick or Greatrakes and wrote a book about him. The Miraculous Conformist, or An account or severall Marvailous Cures performed by the stroaking of the Hands of Mr. Valentine Greaterick, with a Physicall Discourse thereupon, in a Letter to the Honourable Robert Boyle Esq. (1666).

This book, which begins with an address to Willis, has really very little to do with deafness, apart from this short gem, which probably explains why Selwyn Oxley added it to the collection –

I saw him put his Finger into the Eares of a man who was very think of Hearing; and immediately he heard me when I asked him very softly severall questions. I saw another whom he had touched three Weeks agoe for a Deadnesse in one Eare, who I had known to be so many years: I stopped the other Eare very close, and I found him to hear very well, as we spoke in a tone no way raysed beyond our ordinary conversation.(p.6)

Greaterick was a ‘stroker’, using his hands to rub the body of the patient and effect a ‘cure’ by rubbing the sickness out, perhaps through the toes. Stubbes was at pains to say that any cures were through God and not the devil, and that Greaterick prayed – “I observed that he used no manner of Charmes, or unlawful words; sometimes he Ejaculated a short prayer before he cured any, and always after he had done he bad them give God the Praise.” (p.8). People noticed that he smelt fragrant, and “Dean Rust observed his Urine to smell like Violets, though he had eat nothing that might give it that scent.” (p.11).

the notion I have concerning Mr. Greatericks is the most facile, for I imagine no more to be in him, than a particular Temperament, or implanted Ferment, which upon his touching and stroking shall so farre invigorate the blood, spirits, and innate temperament of the part (Nature being only oppressed) that they performe their usuall duties: This being done, it is Nature Cures the Diseases and distempers and infirmities, it is Nature makes them fly up and down the Body so as they do: they avoyd not his Hand, but his Touch and stroke so invigorateth the parts that they reject the Heterogenous Ferment, ’till it be outed the Body at some of those parts he is thought to stroke it out at.

Considering that our life is but a Fermentation of the Blood, nervous Liquor, and innate constitution of the parts of our Body, I conceive I have represented those hints and proofs which may render it imaginable that Mr. Greatericks by his stroking may introduce an oppressed Fermentation into the Blood and Nerves, and resuscitate the oppressed Nature of the parts. (p.14)

It is easy to laugh now but these were days before modern medicine when any attention for a desperate person from someone who might effect a treatment would be welcome. However I cannot resist a few more examples. Greaterick is supposed to have cured, in the presence of Lord Conway, a boy of fourteen of leprosy.

Mr. Greaterick stroked him again, rubbed his Body all over with Spittle. My Lord ordered the Boy to return, if he were not Cured: but he came no more (p.28).

We are not told whose saliva, but anyway the dice are loaded – he should have had the boy return if cured.

A woman of Worcester having a paine driven into those parts which modesty would not permit her to let Mr. Greaterick stroke: she went away as if she had been cured, but is since sick of an intolerable pain there. Such consequences are usuall, when the Disease is not stroked out (p.29).

Stubbe later fell out with the nascent Royal Society – “Not only did Stubbe believe that the protagonists’ claims regarding the utility of science were vastly exaggerated, but he was convinced that their inflammatory rhetoric seriously threatened the humanist culture of the universities, the erudite foundations upon which protestantism rested, as well as the medical profession.” (ODNB) Stubbes, who clearly had a talent for controversy, drowned in a shallow River near Bath, as his friend Anthony Wood wrote, “‘his head being then intoxicated with bibbing, but more with talking, and snuffing of powder’” (quoted in ODNB).

Below, Greaterick stokes Lord Arlington – click for a larger image.

Mordechai Feingold, ‘Stubbe , Henry (1632–1676)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26734, accessed 25 Sept 2015]

Mordechai Feingold, ‘Stubbe , Henry (1632–1676)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26734, accessed 25 Sept 2015]

Carl B. Estabrook, ‘Stubbes , Henry (1605/6–1678)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/26735, accessed 25 Sept 2015]

Close

Close