Disadvantaged pupils have less-qualified science teachers across the developed world, and other findings from PISA

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 14 June 2018

Sam Sims.

The Programme for International Student Assessment is a well-known exercise in benchmarking pupil attainment in maths, science and reading across countries. PISA was first conducted in 2000 and five further rounds of results have since been published. Around 80 countries are taking part in 2018.

What is less well known is that PISA also collects information from school leaders about their teachers, such as the qualifications they have and the training they receive. The OECD, who manage PISA, also collect information on differences in national policy towards teachers, through parallel research programmes.

The OECD have now brought this information together to examine whether national differences in teacher policy can explain countries’ performance on PISA tests. The resulting dataset covers an unprecedented range of countries, in quite some detail. What can we learn from it?

The report includes some striking descriptive findings about access to teachers in state-funded schools. Thirty-four of the seventy school systems allocate more teachers per pupil to disadvantaged schools than they allocate to more affluent schools. Only one, Montenegro, does the reverse.

PISA also collects two widely used proxies for teacher quality. Twenty school systems have disadvantaged schools that are worse off in terms of the proportion of their science teachers who have a science degree, compared to more affluent schools. Strikingly, none of the economically advanced countries in the data achieves the opposite. A similar pattern holds for the proportion of uncertified teachers.

The report therefore suggests that, across a very wide range of countries, policy is succeeding in allocating the quantity of teaching resources in a way that helps disadvantages pupils, but failing to do the same with respect to the quality of teaching resources.

This begs the question, what can policy can do to help? It is worth pausing to consider what, if anything, such international comparative exercises can tell us in this regard.

One strength of the PISA data is that around 50 countries have now participated four or more times. This allows researchers to disentangle the effects of influences on pupil attainment that are stable over time, such as cultural norms. The OECD exploit this to show, for example, that where teacher pay has become more competitive over time, results have improved. Yet even with this longitudinal variation, it is still difficult to make the types of causal inferences necessary to inform policy. Perhaps economic growth caused both increased pay and increased pupil attainment.

This does not however mean the report offers no policy insight. As always, this analysis is most useful when considered in conjunction with other types of research.

We already have evidence, for example, that increasing school autonomy, or making teaching attractive to more graduates, can improves pupil attainment. This information comes from experiments and natural experiments, which provide strong evidence of a causal link in a given setting.

The problem with experiments is that they provide no evidence that the same policy-outcome link will hold in a different setting. This is particularly pertinent for teachers, who have very different social status, pay, working conditions and employment opportunities across countries. Replicating the experiments in each country would be slow and expensive. Indeed, it may never happen.

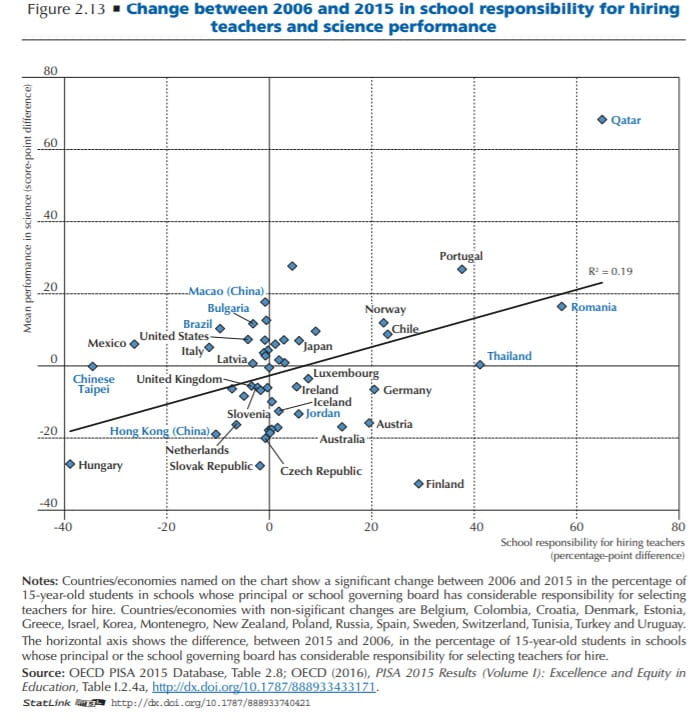

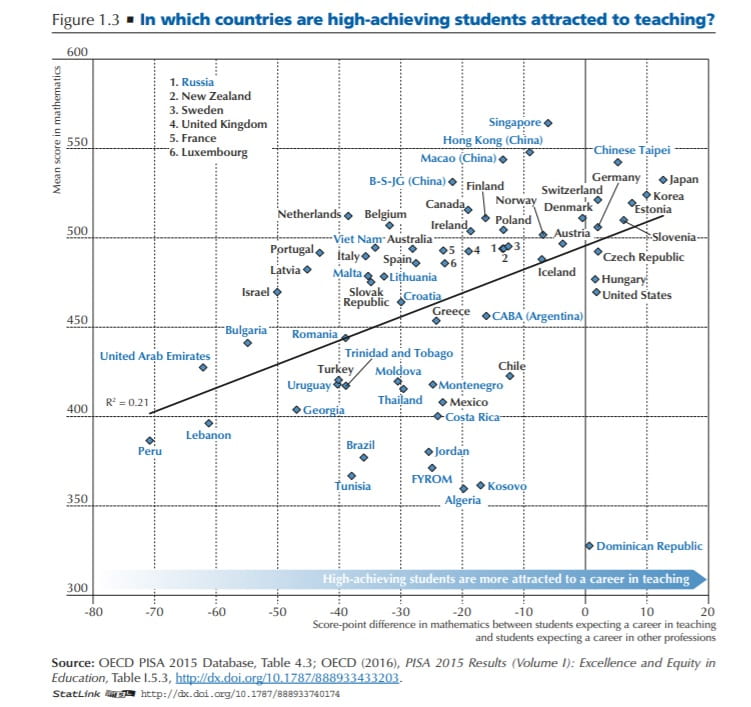

The PISA data helps shortcut this by showing whether these same policies are associated with increased performance in 70 different school systems. In the OECD analysis, both increasing school autonomy (Figure 2.13) and making teaching more attractive to graduates (Figure 1.3) are associated with increased pupil attainment across countries.

When considered in conjunction with experimental evidence, this cross-country research therefore helps generalise and broaden our knowledge about what works where in teacher policy. That is a very useful thing for policymakers to know.

2 Responses to “Disadvantaged pupils have less-qualified science teachers across the developed world, and other findings from PISA”

- 1

-

2

goalsattainment wrote on 12 August 2018:

Should we hold PISA in such high regard. Could, like football, we move our sights from the domestic problems we face to competing on the world stage. At the detriment of the young people in our schools. Its very hard to win the double, just ask the big four premiership teams who spend millions competing on two sometimes three fronts. We need to focus on fixing the inequality in our schools before we set our sights on winning something meaningless to our young people.

Close

Close

What is the point of the IoE if it’s just uncritically going to repeat the ‘findings’ of PISA? The above reads like an extended press release and is better-suited to journalism. More informed critique please.