Early school leaving still blights English education

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 4 March 2015

Andy Green

Early school leaving has always been a blight on the English education system. Throughout the nineteenth century children tended to leave school earlier than elsewhere in northern Europe. This continued well after the 1944 Education Act introduced free ‘secondary education for all’. By the early 1980s, barely more than 30% of 16-18 year olds were in full-time education and training, compared with well over 70% in Japan, Sweden and the USA. The proportion gaining a higher level qualification was also relatively low. UK-wide, only10% gained three A levels compared with over 20% gaining the Abitur in Germany and an even higher proportion achieving the Baccalauréat in France.

Wanting to understand this startling disparity, along with the exceptional underdevelopment of vocational education and training in England, was one of my motivations for undertaking doctoral research on education and state formation at that time. But you don’t have to study all the history to get a sense of the reasons for this peculiarity in England. It’s probably enough to ponder the astonishing fact that for many years after the introduction of ‘secondary education for all’, governments would not allow the secondary modern schools, which educated most children, to prepare their students for O levels (let alone A levels). Even by the early 1960s less than one in ten secondary modern students took O level exams, without which you could not take A levels or prepare to enter university. The bare fact of the matter was that post-war governments (and this included Attlee’s Labour Government) did not consider most children worthy of academic qualifications. So much for equality of opportunity.

Participation in upper secondary education and training has, of course, improved markedly during the past 35 years, boosted by labour market demands for higher qualifications and by some good policy measures, such as the introduction of the single GCSE exam in 1986, and the Education Maintenance Allowance, which encouraged young people to stay on after 16. Now most young people do stay on for a year or two. But the trouble is that many only take part-time or short, full-time courses, often of low quality and leading to qualifications without value on the labour market, as documented in the Wolf report. Well over a third have already left education and training before the age of 18. Eurostat figures for 2013 show that only five of the EU 28 countries had higher rates of young people leaving without full upper secondary education and training (which in most countries means until 18 or 19 years of age).

Why does this matter? Well for one thing, in today’s highly competitive youth labour market you don’t have much chance of a decent job unless you have at least a full upper secondary qualification (which in England would usually mean two A levels, an IB, a BTEC National or possibly an NVQ3). Of the myriad qualifications we offer 16-18 year olds these are the only ones which genuinely match the criteria of the OECD’s ISCED level 3 (long) courses, which OECD consider the minimum for functioning successfully in the modern world. Less than 60 percent are getting these qualifications currently in England.

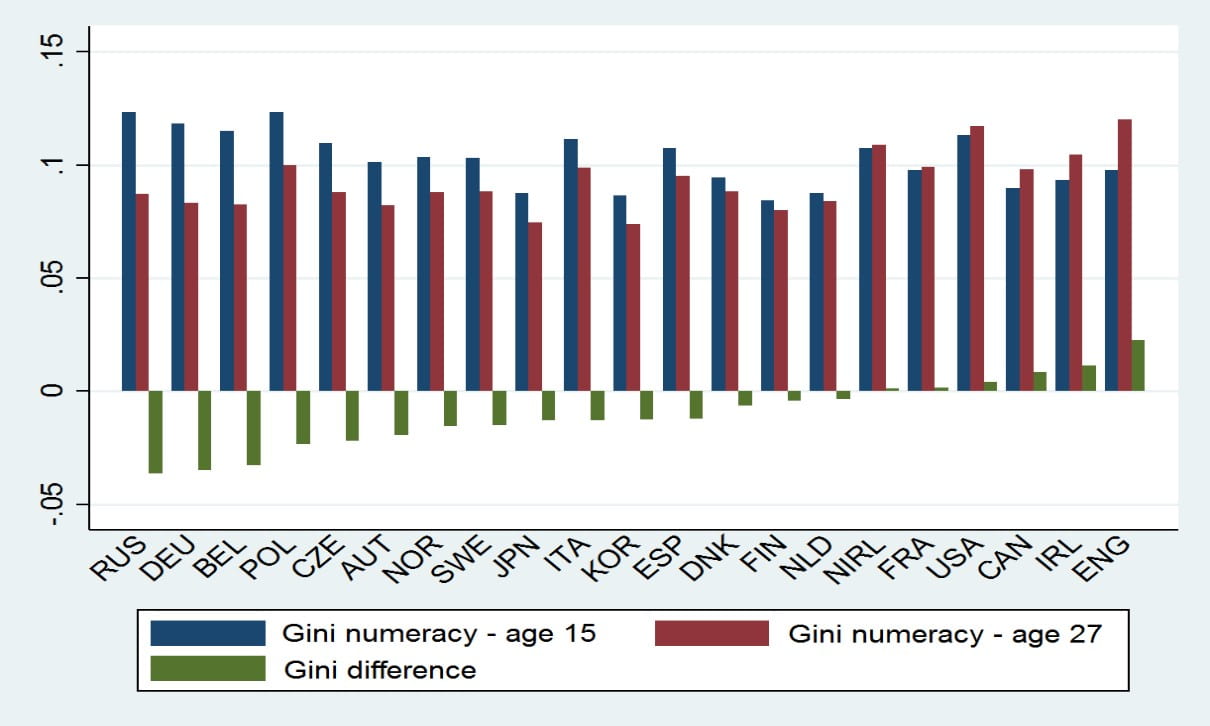

Secondly, early school leaving seems to explain a good deal of the relatively high level of skills inequality we find amongst young adults in England. My new research with Nicola Pensiero shows that post-16 education and training in England is singularly failing to reduce the high levels of skills inequality that has already emerged by age 15, according to the PISA test data. Comparing PISA 2000 results for 15 year olds with the results for 27 year olds in the 2011 Survey of Adult Skills, we can see that between the ages of 15 and 27 in England literacy inequality barely reduces, and social class gaps in achievement increase significantly. In numeracy the situation is even worse, with the spread of scores widening substantially and the social class gaps in achievement growing more than in any other country studied. The result is that 27 year-olds in England show a more unequal distribution of literacy and numeracy skills than any of the other 23 countries surveyed.

Change in Numeracy Skills Ginis between 15 and 27

How do we explain this? The countries which do most to mitigate skills inequality after age 15 are those with high participation in good quality three-year apprenticeships, like Austria and Germany, or with high completion rates from long-cycle upper secondary education, as in most Nordic and central and eastern European Countries. Countries like England – and most other Anglophone countries – which have high rates of early leaving, and a profusion of short courses of variable quality, tend to fare worse. Lower achievers in England are not benefitting from the extra two or three years of learning maths and the national language in dedicated classes with specialist teachers, which is the norm in these other countries. Consequently they are not having the opportunity to close the skills gaps with their higher achieving peers.

ISCED 3 Completion and Mitigation of Inequality in Numeracy Skills

What do we need to do about it? The Government’s raising of the participation age to 18 in 2015 is a step forward but it still allows young people to take an ad hoc collection of short general or vocational courses (including part-time study) many of which do not lead to a useful qualification. Furthermore, 16 to 19 year-olds are only required to reach, or be working towards achieving, the equivalent of GCSE A*-C in mathematics and English, which is a lower standard than that expected for qualifying at upper secondary level in most countries.

A more effective option would be to develop more standardised pathways post-16, with all students encouraged, with maintenance grants where necessary, to take two or three year programmes, which would include maths and language tuition delivered in dedicated classes by specialist teachers. Assessment should be through a grouped award at the end of upper secondary education, requiring an appropriate standard in English and maths. I’m getting a sense of déjà vu here! Didn’t we propose this in the early 1990s with the British Bac? Tout ça change…

Close

Close