After our team gathered in London this past May, we came back to the field with four main tasks, one of which is to apply a new questionnaire to one hundred participants. Now that this mission is nearly accomplished, I am surprised by what I learned from the questions that, for various reasons, did not work and also by the ones that did. The application of a questionnaire forced me to contact people outside the groups I am closer to and provided a valuable opportunity to check if the generalizations I have made so far are correct. At the end, the questionnaire showed how quantitative methods could be misleading as people either don’t understand or differently evaluate the questions they are faced with. But they can and should be used in the context of long-term qualitative research as the researcher is then able to learn not just by the responses, but also mainly by the information that is offered beyond what the questionnaire requests.

On this blog post I will present some of the qualitative insights the application of this questionnaire has provided.

Right at the beginning of the conversation we ask the informant how many friends she or he has on their preferred social networking site. My expectation was that teenagers would have thousands of friends while everyone else would have about a few hundred or less. This has been the case among some participants, but as I applied the questionnaire often I heard the following intriguing reply by everyone including teens: – “Oh, I have loads of friends there. About 60…” There are quite a few things that can be unpacked from this answer. One is that I realized my teenage informants were heavy users and they were not representative of the entire group of people in their age group. Besides that, it is intriguing that having 60, 80 or 120 can be perceived as being a great number and I can now ask around to find out why is that so.

Some questions confirmed perceptions the ethnography uncovered. Later on in the questionnaire, we ask how many of the person’s friends on social networking sites the informant has never met face to face. Although I am Brazilian like my informants, their notion of what a Facebook contact should be is clearly different from mine. A “friend” here is everyone you can know, which is a group that includes the people that knows the people each one knows (friends of friends). Very few of my respondents answered that they knew personally everyone from their network. The typical reply was that loads of those they were friends with on Facebook they had added because, among other reasons, they had friends in common. So through sites like Facebook we see that my informants understanding of an acquaintance is much wider and flexible than that of people with my urban middle class background.

My informants have not understood the question that helped me realize this previous observation. Originally our research team wanted to know if informants asked the permission of friends or of family members before adding people to their network of contacts. As I read this question to informants, they replied to it quite quickly and confidently so it was not until almost finishing this task that I saw they had understood something very different from our original intention. They usually answered that they consulted friends before adding new contacts, but they were actually saying that when they receive a request from someone they haven’t met and don’t know, they go to this person’s profile and browse around to find out, among other things, who these people are friends with. Having friends in common is an important aspect in the decision of accepting friendship requests.

Some questions worked out incredibly well. One of these asked: do you feel that the opportunity of interacting with people through the Internet has become a headache? This was clearly understood by everyone and it will be interesting to see after we process the data if there are specific demographic groups that replied affirmatively to it. For example: young married people apparently both enjoy meeting more people and are bothered by having their lives more closely monitored by their partners. Others said that Facebook mixes up together different groups of people and it has become a burden to deal with frequent tensions inside one’s network.

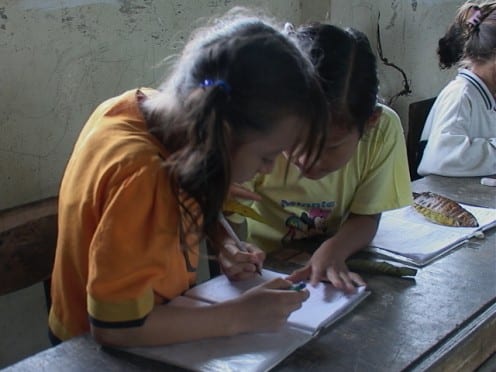

We ask informants whether they think social networking sites are good or bad for education and for work. Although some replied Facebook was bad for education because it captures the attention of students out of their schoolwork, several parents consider it positive for exposing their children to information and knowledge. The answers were even more emphatic about work. As Baldoíno is a working class village, many of my informants here work in hotels, are private security guards or have small businesses and having the possibility of communicating with peers and with business partners easily and without paying is very helpful.

On the whole, my informants could not say whether they had “liked” businesses on Facebook. It is unclear to almost all what the difference is between, for instance, a soap opera and a company, and notions such as “local”, “national” and “international” in regard to the businesses they “liked” were confusing to them. Why shouldn’t Coca Cola be local or national if its products are available locally and their adverts are running on national TV channels? Some informants answered that they have purchased items from the businesses they follow, but what they mean is not that the purchase happened as a consequence of them “liking” the business. They like the product and they express this by “liking” them on Facebook and buying products.

I was surprised to see how the people here understand the Facebook timeline. In my private use of Facebook, friends rarely publish stuff on my timeline; as a whole, we share the understanding that one’s timeline is a private place that should not be used by others unless on specific occasions such as birthdays. Here in Baldoíno leaving messages of all sorts in someone else’s timeline is part of the way Facebook is used and the word “timeline” has become part of the vocabulary people use to talk about social networking online.

The questionnaire ends with two questions about politics and the answers I collected are revealing of the particularities about this place. I think all but one person said she or he had unfriended someone because of political differences. Many said that they have unfriended people because of quarrels motivated by other reasons, but not because of politics. These answers reveal the physical distance that in fact exists between them and local representatives. Politics is a topic not worth quarreling about because there is nothing to gain from it. Government type of politics represent a burden that has to be dealt with every two years during elections and politicians are very present during that time but afterwards they disappear.

Although informants consistently said they didn’t care about politics, most said confidently that social networking sites have made them more politically active. They were very sure about both answers so I started asking what they understood about being politically active. Initially I suspected they meant Facebook allowed them to be more active in their community as they are now able to complain publicly about things they don’t like, but this was not what many were trying to say. By being more active politically they are saying they are better informed about what happens beyond the daily life in their locality. Facebook is a place that disseminates information so they learn about more things that are interesting to them that they don’t get through other media such as the television.

There is a lot more to say about this experience and about how quantitative methods can be a valuable tool to acquire qualitative data, but hopefully the examples offer possibilities for this subject to be discussed further. I am curious to learn how the experience has been for my research colleagues and hope they blog about it here as well.

Filed under Brazil, Business, Culture, Fieldsites, Methodology, Politics, Themes

Tags: Brazil, ethnography, Facebook, Friends, friendship, Politics, privacy, public, qualitative, qualitative data, qualitative research, quantitative, quantitative data, questionnaire, research, research method, social media, WhatsApp

5 Comments »

Close

Close