Why Facebook but not Twitter

By Jolynna Sinanan, on 21 January 2013

by Daniel Miller and Jolynna Sinanan

Image courtesy of Beth Kanter, Creative Commons

During the time we have been conducting joint fieldwork in Trinidad, we have been developing through conversations an argument that perhaps Facebook is the revenge of most of the world against the internet. This builds on arguments in Tales From Facebook that suggested that so far, instead of being the latest iteration of the internet following the same trajectory, Facebook actually reverses several trends as it re-socialises peoples networking, for example, it brings back into visibility the nature of ‘community’, where instead of sharing a nostalgic view, it reminds us that community is close knit, everyone is visible to everybody else, and everybody knows about everybody else (2012). Indeed, the problem with most studies of networking today is that they confuse two forms of networking, one of which is largely instrumental and focused upon the more effective modes of transmitting and obtaining information in this ever more diverse and complex world. This for example, is a key imperative to ‘bridge and build social capital’, to create ‘knowledge and ‘information networks’ in many development programs, where social networks are viewed as an untapped resource for creating information networks, indeed, instrumental networks (Craig and Porter, 2006, Li, 2007). This was and remains the main imperative behind the internet itself. Rainie and Wellman and Castells for example, speculate and argue for the avocation of a knowledge based society, where people are the nodes for transferring information (2012, 1996). The other is the traditional networking of social relations that actually turns people from what are generally regarded as these significant advances, favoured by the field of development studies, and instead re-orients them to the trivial everyday stuff of our social banter and exchanges. In short, it helps bring them back to the sort of worlds traditionally studied by anthropologists, but which are just seen as a kind of barrier to breaking through to the educational and informational future of development. So, not only should informational networks and social networks not be confused, which is a constant problem of networking studies, but they are often in contradiction to each other.

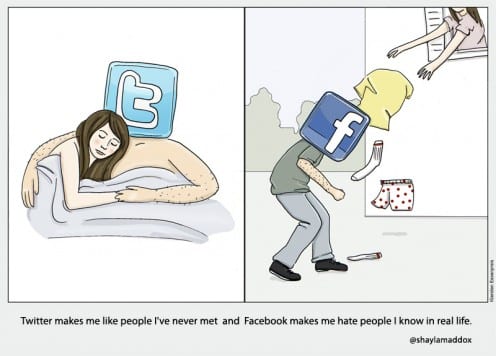

In Tales from Facebook, the argument was that Trinidadians took to Facebook with alacrity because it finally allowed online activity to express traditional values that foregrounded social over informational content. Indeed, today, it is increasingly items such as political news or following latest styles that in Trinidad are being extracted from the wider internet and relocated within the more socialised environs of Facebook. But what then happens to Twitter, which superficially looks a bit like a social network such as Facebook but in another way, is its inverse? Twitter is among other things, a means to use social networks to effectively transmit and obtain information, which is why it is much closer to conventional journalism and older mass media. If that is the case, then what would Trinidad do with Twitter? The answer was not clear during out fieldwork in 2011-2012 since Twitter was new and Trinidadians will always adopt the latest thing (much of our current fieldwork is about WhatsApp). But by 2013 we have a clear answer. Trinidadians have almost entirely rejected Twitter. Our informants say they tried it for a while but then abandoned it. The story may be different for the more cosmopolitan population of the capital, but in our small town, Twitter is dead as a dodo. Yet Facebook continues to flourish and becomes ever more dominant. We believe that the reasons closely conform to the problems similar populations have with development projects. They resist attempts by top down initiatives that lead to more abstract, de-socialised agendas focused on efficiency and information. They use against these, the strength of contextualised social networking. Thus our initial statement, that perhaps Facebook is much of the world’s revenge again the internet.

References

Castells, Manuel, 1996, The Rise of the Network Society, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture Vol. I. Blackwell, Oxford

Craig, David and Porter, Doug, 2006, Development Beyond Neoliberalism? Governance, Poverty Reduction and Political Economy, London, Routledge

Li, Tania Murray, 2007, The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development and the Practice of Politics, Duke University Press, Durham and London

Miller, Daniel, 2012, Tales from Facebook, Polity, Cambridge

Rainie, Lee and Wellman, Barry, 2012, Networked: The New Social Operating System, MIT Press Cambridge, London

Close

Close