Expanding beyond our project – kinship in the light of social media

By Daniel Miller, on 26 July 2016

. @DannyAnth speaking at our #EASA2016 #SocialMedia and #kinship panel right now! @EASAinfo @UCLWhyWePost pic.twitter.com/CIpLWzSXrw

— Tom McDonald (@AnthroTom) July 22, 2016

The recent meeting of the European Association of Social Anthropologists in Milan was the first time we have engaged in a collaborative consideration of a topic linking our team’s research with that of others working in similar research areas. The chosen topic was kinship in the light of social media. From our own team, Elisa spoke about the use of social media for reconstituting tribal identity amongst Kurds, Tom spoke about how rural Chinese actually seek out strangers using social media, Xinyuan discussed the use of social media to re-orientate from kin to other forms of socialisation and Razvan discussed how people in South Italy re-constitute kin within wider relationships. My own paper was on the development of ‘fictive friendship’, i.e. how kinship is increasingly modelled upon friendship.

Up now: @razvanni on #SocialMedia use and separating interior & exterior lives in #Italy. #EASA2016 @UCLWhyWePost pic.twitter.com/5G5Ou6rKTR

— Tom McDonald (@AnthroTom) July 22, 2016

But for us the most interesting development was seeing our work in juxtaposition with the work of others. Gabriele de Seta of Academia Sinica Taiwan presented the aesthetics of visual posts by older Chinese users of social media and how these are strongly differentiated from those that had been established amongst younger users. Giovanna Bacciddu of Pontifica Universiad Catolica Chile, explored the use of social media to connect Chilean birth parents with their children who had been adopted in Italy. Gulay Taltekin Guzel and Alev Kuruoglu of Bilkent University Turkey, showed how religious Muslim newlyweds in Turkey establish a site to discuss the moral and other norms of married life. Finally, Roger Canals of the University of Barcelona looked at how kinship and religious ideals are interwoven in the aesthetic of social media representations of the cult of Maria Lionza in Venezuela.

.@AnthroTom giving a lively & thought-provoking talk on strangers, kinship & Chinese social media #EASA2016 pic.twitter.com/0VNwH3aMXE

— Resto Cruz (@RCruzAnth) July 22, 2016

Taken as a whole the session, which produced a very lively and engaged discussion, showed why this will always be a central topic within the anthropological study of social media. It is not simply that the family is one of the foundations for so much usage of social media, including new platforms such as WhatsApp. Nor even that social media is often important in itself for helping people create new relationships with kin which may include the repair of ruptures in the family thanks to migration, but it can also mean creating new distance from kin in favour of other forms of sociality. Above all it became evident that we cannot understand the development of social media itself, except through seeing it in part as a reflection and manifestation of wider changes in kinship relations and the rise of other relationships models such as the stranger or friendship. Fortunately, the study of kinship is perhaps the single best established tradition in anthropological scholarship and it seems a very productive means to re-engage this traditional scholarship with an entirely new medium.

. @elisax00 presents her work on #tribes, #Kinship & #SocialMedia among kurds in Turkey. #EASA2016 @UCLWhyWePost pic.twitter.com/meVak9uCVb

— Tom McDonald (@AnthroTom) July 22, 2016

Making a MOOC: Social Dynamics and Ecological Design

By Laura Haapio-Kirk, on 7 July 2016

Guest post by Sheba Mohammid, a fellow on the Why We Post project. Sheba is a PhD candidate at RMIT University in Digital Anthropology/ Media and Communications and was previously Coordinator of the National Knowledge Gateway of Trinidad and Tobago.

I recently had the opportunity to conduct an 18-month ethnographic study of digital media use and learning in Trinidad and Tobago. In the process of analysing the findings, the Why We Post Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) was also being designed. The Why We Post team at UCL had a genuine interest in making their research available to the widest possible audience in learner-centred ways. One of these approaches is the MOOC that is currently making its second run. The team also has a keen interest in improving the MOOC and also seeing where the MOOC fits in a menu of resources. MOOCs have been in mainstream discussion, garnering both praise and critique. As my research on out-of-school learning was wrapping up and the MOOC was being created, there was further opportunity for discussion on the challenges and opportunities in making an effective MOOC and what this could potentially mean. In following my participants, my research focused on a low-income community. Here I found learning being performed in complex and nuanced ways that resist simplistic pedagogization but still produce some probing questions for considering the multiple dimensions of MOOCS and how they fit into the ecosystemic learning practices I observed.

Participants interested in informal/non-formal learning in the community I studied practiced their knowledge creation, sharing and use in complex ecologies that incorporated multimodal resources, searching, finding and problem solving in online and offline contexts. The reality, though, is that they weren’t using MOOCs. Some were not aware of the courses available while others were not interested in signing up. This resistance was often blamed on time constraints but deeper discussion often revealed that there was a reluctance to take a course because of the pressure that they often associated with formal classes. This was often based on poor educational experience or attainment in their past formal schooling. These participants however did employ many strategies for learning in their day to day lives that often used video resources and interactions that were outside of a bounded course. This may, on one hand, lead to a debate between the virtues of xMOOCs and cMOOCs, but it also begs a deep consideration of where MOOCs fit in the ecosystemic approaches to learning that acknowledge that people traverse a variety of everyday terrains in their learning. Does the MOOC fit into a wider ecology of resources where people who want to view the videos separately, for instance, are free to do this while the people who want to take a structured course can sign up for it? Should the MOOC itself be resistant to being a replication of a classroom and start thinking of more fluid ways that encourage different approaches? For instance, my study participants often associated traditional education with a measure of shame-based learning where failure was very much maligned. The identity of the learner and his/her feelings of success were often tied to being able to demonstrate getting things “right” in very public ways.

In studying the social dynamics of informal learning among my participants, I observed that their practices involved deep negotiation of failure, experimentation and non-linear, iterative learning. A lot of normative discourse about the internet emphasises the potential of technology to promote collaboration. I found that the dynamics at play were more complex than this as people were also using the internet in their learning to navigate sociality in ways that allowed for privacy for their own experimentation. People who were learning crafting through YouTube videos often confessed that they had never saw themselves as creative nor felt comfortable in school settings unless they thought they were good at a particular subject. They were however willing to invest time in processes of trying, failing and experimenting using YouTube videos on their own. The internet was a resource that allowed them greater control of their privacy in learning. They were then able to negotiate when they would share their process for feedback within their communities. Collaboration is often emphasised as a key facet of learning in MOOCs. Does collaboration become forced, however, and a tyranny in itself that does not acknowledge the multifaceted ways that people learn through individual reflection, privacy, sharing and interaction?

The communities my participants were involved in often were not online or based on a shared subject interest but a mix of their everyday relationships. If the participants in Trinidad and Tobago were being measured on online participation such as uploading their own videos or comments, it would seem that they were not particularly active. When their learning practices were viewed in relation to the wide ecosystem of their everyday lives and the complex sociality therein, it became clear, however, that they were moving through a number of offline contexts sharing and constructing their knowledge. It was not only their competence in their expertise that affected their perceptions of performance. A dimension I saw as social confidence or confidence within and of their social contexts was as key a factor as subject content. These Trinis were navigating their learning, interactions based on feelings of social confidence as they were negotiating their social confidence itself.

MOOCs are often measured on collaboration and online participation. In considering the ecology of how learners practice informal learning, however, a series of questions can be posed:

- How do we best conceptualise the MOOC as a resource and a space in a wider ecosystem of resources and spaces?

- How do we factor for design that values the nuanced dynamics of an ecology of learning in which people have spaces for individual reflection and interaction?

- How do we incorporate offline elements into MOOCs that leverage everyday communities and relationships?

- How do we create spaces where people can build subject competence and social confidence?

- How do we measure MOOC success on the intent of the people who are using it as a resource? Are completion rates the best measure or is utility to participants based on their criteria a better success factor?

MOOC architects, designers or users are still in the process of negotiating the answers to these themselves. But in starting with the participant’s perspectives and the complex dynamics of their practice, we are creating an agenda to improve learning in ecosystemic ways with MOOCs playing a role in this ecology.

Are you currently taking the Why We Post course on FutureLearn or have you previously taken other MOOCs? Where do you see the MOOC fitting in your wider learning? Was it a successful experience for you?

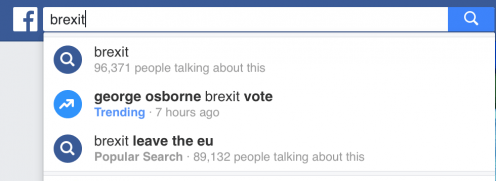

Social Media and Brexit

By Daniel Miller, on 27 June 2016

One of the common claims made about social media is that it has facilitated a new form of political intervention aligned with the practices and inclinations of the young. Last week I attended the launch of an extremely good book by Henry Jenkins and his colleagues called By Any Media Necessary which documents how young people use social and other media to become politically involved, demonstrating that this is real politics not merely ‘slacktivism’, a mere substitute for such political involvement.

And yet, currently I am seeing social media buzzing with young people advocating a petition to revoke the Brexit vote, which only highlights the absence of a similar ‘buzz’ prior to the vote. I await more scholarly studies in confirmation, but my impression is that we did not see the kind of massive activist campaign by young people to prevent Brexit that we saw with campaigns behind Bernie Sanders in the US and Jeremy Corbyn in the UK.

The failure to create an attractive activist-led mass social media campaign to get young people to vote for Remain is reflected in the figures; although 18-24 year-olds were the most favourable segment towards Remain, only 36% of this group actually voted at all. As such, Brexit represents a catastrophic failure in young people’s social media, from which we need to learn. Being based in ethnography, our Why We Post project argued that we need to study the absence of politics in ordinary people’s social media as much as focusing on when it does appear. But the key lesson is surely that just because social media can facilitate young people’s involvement in politics doesn’t mean it will, even when that politics impacts upon the young.

One possibility is that social media favours a more radical idealistic agenda. By contrast, even though the impact of Brexit might be greater and more tangible, the remain campaign was led by a conservative prime minister, backing a Europe associate with bureaucracy and corporate interest, and was a messy grouping of people with different ideological perspectives, that made it perhaps less susceptible to the social media mechanisms of aggregated sharing.

At the same time I would claim that our work can help us to understand the result. My own book Social Media in an English Village is centred on the way English people re-purposed social media as a mechanism for keeping ‘others’, and above all one’s neighbours, at a distance. I cannot demonstrate this but I would argue that by supporting Brexit the English were doing in politics at a much larger scale exactly what my book claims they were doing to their neighbours at a local level: expressing a sense that ‘others’ were getting too close and too intrusive and needed to be pushed back to some more appropriate distance. And it is this rationale which may now have devastated the prospects for young people in England.

Hear Daniel Miller talk about social media and politics in this Why We Post podcast.

Un Manjar: Viral Chilean slang

By ucsanha, on 12 May 2016

In Chile, “manjar” is a kind of sweet sauce, similar to dulce de leche or caramel. It’s often used as filling in layer cakes or atop pancakes. It is almost universally loved for its smooth rich flavour. But ‘manjar’ is also used in slang to mean ‘rich’ or ‘sweet’ in other contexts as well. One may refer to a delicious holiday meal as ‘un manjar’ or equally to their love interest.

I had heard these uses of the word in Chile, and also being a fan of the sweet sauce, it made sense that it stood in for something to be savored. Yet when I attended a concert by American rock band Faith No More in Santiago, I was bewildered by the crowd’s repeated chanting of ‘un manjar! un manjar!’. Sure, the music was good, something to be savoured in the moment, but the food metaphor just didn’t seem apt to me. And the fact that it was being chanted in unison by thousands rather than whispered with a wink as that especially attractive acquaintance passed by, puzzled me even more.

But then I realised it was simply the buzz word of the moment. And not because of some fluke, but because, as is usual these days, social media had set off the trend, much as I explained for the resurgence of The Rhythm of the Night in Chilean night clubs in 2015.

In this instance, ‘manjar’ was thrown into heavy circulation when a youtube video surfaced of a Chilean campesino [person from the countryside] taking a long swig of very cheap wine, and then in a slow gruffy voice, proclaiming ‘un manjarsh’. Because of his accent and stereotypical campesino look, the man’s drunken proclamation was hilarious to young youtube viewers and as the video was passed around, use of the word ‘manjar’ shifted from occasional to self-consciously inserted into any possible exchange. Not only in spoken language, but Whatsapp messages, Facebook posts, Tweets, .gifs, memes, and even parody videos flooded Chileans’ internet. After a week or two the joke subsided, though when casually used, even several months later, the word still conjures the video of the campesino and his wine.

So, sure, this is just another story in grand quantity about how a word, idea, or image goes viral, has a short-lived moment in the spotlight, then fades from memory. But in this case, it also tells us something about nationalism and popular culture. Because manjar is considered something of a staple food in Chile, to call a person, food, or drink ‘un manjar’ not only says that the object is desirable, but that the person speaking about it does so from a particular position of being a ‘true Chilean.’ In some ways, urban youth may be lampooning the campesino with wine, but they are also identifying a similarity between him and themselves as Chileans. And when shouting it at an international rock concert, it claims the space and music as Chilean, not foreign, appropriating such rock music into a ‘true Chilean’ repertoire. I suppose it would be something like Americans chanting ‘apple pie’ at a U2 concert, claiming them as their own.

Apple and the Smartphone market in India

By Shriram Venkatraman, on 6 May 2016

Photo Courtesy: CC: Wikimedia Commons: Kārlis Dambrāns from Latvia

Less than a fifth of the Indian population might own a smart phone, but India is now the second largest smart phone market in the world. The large phone manufacturers see immense potential in the buying power of the Indian population. While the international brand Samsung dominates the smart phone market in India (with phones manufactured for the south asian market), the Indian brand Micromax has its own set of customers as well. Reports suggest close to 150 smartphone brands in India and estimate the market to grow with the Make in India/Digital India drive. Each of these brands have varied price points and customise their mobile handsets to the Indian consumer market.

While this has generally been the case with India, companies such as Apple have been trying to engage with the mobile consumer market, though their market share has been low, their revenue share has been high. Suggestions to increase its market share have been to invest on either innovation and market to the brand conscious (which would mean high end consumers) or contextualise its price differentials and compete with the low cost players in the Indian market, which can be a never ending game.

Suggestions for market penetration for brands such as Apple, also speak of contextualising and understanding the socio-cultural aspects of a society and play to it. However, the smartphone penetration in India has a long way to go. Even with initiatives such as Digital India, their optimistic estimation of the smart phone consumer market in India seems to be exaggerated, since they leave out the crucial aspect of infrastructural development (electricity/internet data) needed for the smart phone market. For now, all such strategies seem to be around the urban market or promising second tier Indian cities.

Large segments of the rural markets not only have socio-economic constraints but also have major issues with infrastructure. Even with all the monthly instalment schemes on offer by phone retailers, it seems doubtful that even the rich in the rural areas might opt for a costlier branded phone, since it has no use other than voice communication in a rural set up, which even a cheaper smart phone/feature phone can offer. Hence, a high-end brand like Apple might not even work for major sections of Indian population.

For any growth to take place in the Indian phone market, manufacturers have to realise that this is an eco-system, which is based on several aspects including infrastructure (electricity, internet data etc.) and socio-economic factors (caste, access to phones for women etc.) instead of just concentrating on an exaggerated idea of smart phone market in India.

So, for now, looking at the emerging urban middle class in India, the best bet for brands such as Apple would be to optimise the price and offer a product line playing to the brand conscious urban middle class, since their buying decisions are based on a combination of functionality, price and brand (which is used to differentiate from their peer group).

On the Brazilian crisis, Pentecostalism and thinking out of the bubble

By Juliano Andrade Spyer, on 26 April 2016

Pentecostal service in the Brazilian field site. Photo by: Juliano Spyer

Brazil is in the midst of a heated national debate between people in favour of, and those contrary to, the impeachment of the president. Because of social media, the sharing of different political views is also causing divisions in the private domain among friends and among family members. But a glimpse at the Facebook timelines of low-wage Brazilians demonstrates how millions of Brazilians are actually not interested in this debate.

A text written by a dweller of Morro do Viradouro, a shantytown in Rio, explains why the low-income population is not concerned with the national political debate. The idea that the impeachment is a coup d’état does not convince favelados, he argues, as for them the institutional killing and torture of the military regime (1964-85) never ended. Another low-income group is also not using social media to learn about or share points of view about politics: the evangelical Christians.

The lack of interest displayed by affluent Brazilians for this group appears in a piece by The Economist that circulated broadly in Brazil. It presents how Brazilian congressmen and women justified their vote during the session about the impeachment, highlighting the stereotypical carnivalesque aspect of the event and missing the opportunity to note that many of the reasons for the vote for impeachment referred to family, religion and God. These are relevant topics to 25% of Brazilians who are evangelical Christians.

Market analysts use the expression to ‘think out of the box’ to refer to creativity. An ethnographic version of this expression could be to ‘think out of the bubble’; in the case of Brazil, the bubble is social class.

Among the educated middle-class, evangelical Christians are seen, at best, as religious fanatics, but more commonly as backward, ignorant, and even evil conservatives. Having lived for 15 months conducting anthropological research in a working class settlement in the state of Bahia, I had a more nuanced experience of this group.

Firstly, I saw that although they are morally conservative, evangelical Christians are not stupid or intrinsically dishonest as the stereotypes dictate. Their broad ambition to achieve financial success is, in most cases, a desire to be part of the same world of consumption that the affluent have access to. But beyond that, their contributions to society are almost completely unacknowledged.

Their religious organisations are often more present and active in the lives of socially vulnerable people than the government. Let us not talk of spiritual support to avoid discussing faith and religion. Pentecostal organisations actively promote literacy and also intermediate the contact of church members with specialised services including doctors and lawyers. And by ‘recycling the souls’ of drug addicts and criminals, they provide an unrecognised but priceless service to society – much better than the police could ever hope to offer.

I am not denying that they possess conservative views regarding themes such as abortion or gay rights, but I am offering a more ethnographically-grounded view. There are 100 million Brazilians (half of the country’s population) that belong to the deemed ‘new middle class’ (actually, an emerging working class), and Pentecostalism has an undervalued contribution to this process of socioeconomic change.

The difficulty that more affluent Brazilians have in relating to evangelical Christians is maybe because this group, though generally struggling financially, do not identify themselves with the clichéd and victimised image of poor people. They are improving in spite of social stigmas and the legacy tied to the historical inequalities of Brazil. They are often depicted as fanatics in the media and yet their embracing of education is not mentioned. They are seen as morally conservative but nobody points to the reduction of domestic violence and of alcoholism in evangelical Christian families.

In this regard, affluent Brazilians need to step outside of the class bubble and look at evangelicals with more generosity and interest, and with less prejudice. Then they might be better equipped to understand why evangelical Christians are missing from the debate about politics on social media.

The end…not really!

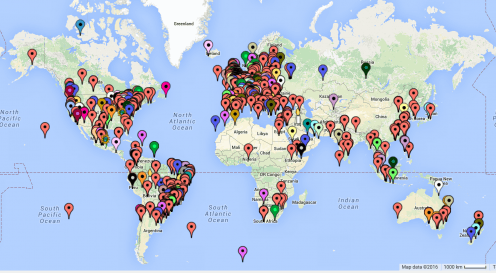

By Laura Haapio-Kirk, on 4 April 2016

Learner locations on Why We Post: the Anthropology of Social Media

The first run of our free five-week e-course, We Why Post: the Anthropology of Social Media, has now come to an end on FutureLearn. We have been delighted by the extent of learners’ engagement with the course, and we thank everyone for sharing their experiences of social media from all over the world. As we have seen, an e-course itself can be a form of social media: a place where learners engage, discuss, and deepen their experience of learning.

The course on FutureLearn might be over, but the learning does not stop here. You can access our course any time on UCLeXtend. And the best bit? It’s available there in the following languages: English, Chinese, Portuguese, Spanish, Tamil, Hindi, Italian, and Turkish.

If you were enrolled on the FutureLearn course but have not yet had an opportunity to complete it, don’t worry: the learning materials will remain accessible. If you missed the course this time, sign up for the next run starting 13th June 2016.

Podcast

We asked you if there was anything you would like to know more about, resulting in lots of brilliant questions. We have tried to answer as many as possible in this podcast featuring Daniel Miller, Xinyuan Wang, Shriram Venkatraman and… a cat.

Go further

If you want to expand on knowledge gained on the course, take a look at our free open access books which contain deeper explorations of the topics and fieldsites that you have already encountered. Our book, How the World Changed Social Media, is an ideal place to begin, offering a comparative analysis summarising the results of the research.

You can also watch over 100 films from our fieldsites on our YouTube channel and learn more about our discoveries on our website.

Keep learning

If this course has inspired you to consider further academic study you might be interested in the MSc in Digital Anthropology at UCL which combines professional development and methods training with a solid grounding in anthropological theory and critical analysis.

We hope that you will continue to think critically about the rich tapestry of experiences that constitute social media and its impact, both in your own life and for others around the world.

Anything but selfies

By Daniel Miller, on 30 March 2016

In every respect we are delighted with the launch of our project. We now engage in daily interaction with thirteen thousand students registered on our FutureLearn course, plus 2,100 on the translated versions on UCL eXtend. The 9,500 downloads of our books is a real boost for Open Access.

But there has been one element that I found rather irritating. Here is a project that dealt with tensions on the Syrian-Turkish border, 250 million Chinese factory workers, the nature of Englishness, transformations in human communication, politics, gender, and education. Yet almost every single media enquiry, and we are happy that there were so many, seemed to focus upon the selfie and almost inevitably mentioned a specific kind of selfie taken in Chile of people’s feet. Which is why, given the choice, I would love to answer questions about our project on any topic under the sun – other than bloody selfies.

But as an anthropologist I have to transcend any personal feelings and always ask ‘why?’. My explanation is going to be as benign as I can make it – what I would like to believe to be the case – though certainly it may be otherwise. My supposition is that the selfie is iconic of social media because it speaks to the single dominant story we want to tell ourselves and which, by creating anxiety, also sells newspapers. We tend to argue that social media is the latest stage in an inevitable journey from the kind of intense kinship-based sociality studied by anthropologists to the fragmented narcissistic individualists studied as a kind of modern pathology by sociologists and psychologists. So the media and others find it strange that it is anthropologists, the group who are supposed to represent the other end of this story – kinship and tribes – who are talking about the selfie. Perhaps this represents a kind of profound disconnect.

It may then follow that the best way anthropology can be presented as a repudiation of this simple story is by noting that as anthropologists we have refused to regard the selfie as this icon of the fall of humanity from the graces of proper and intense sociality. A photo of unpretentious feet is the opposite of the self-absorbed look-at-me selfie of the face. If this explanation is correct it would be parallel to my early blog post about the ‘no-make-up selfie’ where adults in my fieldsite only started posting selfies when they found a cancer charity-based model which seemed to repudiate the association between the selfie and supposed teenage self-centeredness.

We do indeed repudiate the simple story of a decline in humanity and indeed we try and show why even these teenagers are more complex, mature and social than this story implied. If this is the case then I should be happy that the media has made our point so succinctly. Hopefully once that point has burst the selfie boil, this then clears the way for the media and others to focus on the way we tell a hugely different story of highly socialised and diverse social media that has important consequences for almost every other aspect of our lives. For example, the way we use our analysis to critique the very concept of ‘superficiality’ which is the premise of much of this discussion of the selfie. Perhaps now we can argue that in most respects social media takes society in the opposite direction: more social, less individual, closer to the way society is represented by anthropology and less close to the pathologies of the individual studied in psychology. At least that is the story I hope we will eventually be allowed to tell.

Why We Post is “the biggest, most ambitious project of its sort”, says The Economist

By Laura Haapio-Kirk, on 14 March 2016

Since our launch on the 29th February, the first three open access books in the Why We Post series have been downloaded over 6,000 times! 6,000 downloads in just two weeks makes for a very happy team. The entire series of 11 volumes will continue to be released by UCL Press over the coming year, so keep your eyes peeled.

News has spread far and wide of our project and its ambitious public dissemination strategy comprising not only of our books, but a free e-course and a website with films and stories from our nine fieldsites. In the past two weeks we’ve enjoyed global media coverage and have been thrilled with the response from learners on our course who come from all over the world.

Press round-up (29/02/2016 – 14/03/2016):

English:

The Economist (05/03/2016 print and online): The Medium is the Messengers: A global study reveals how people fit social media into their lives

“These fly-on-the-wall perspectives refute much received wisdom… ‘Why We Post’ thus challenges the idea that the adoption of social media follows a single and predictable trajectory.”

The Economist – (02/03/2016 online): Babbage Podcast: From headers to footies (from 06:33)

“(Why We Post is) the biggest, most ambitious project of its sort.”

BBC World Service – (29/02/2016 radio): World Business Report (from 4:13)

BBC Click (02/03/2016 radio): What is the Point of Posting on Social Media

“… a global snapshot of our relationship with the social media… This is a nuanced picture of a world coming to terms with a rapidly evolving way of connecting, or even disconnecting, with something unexpected pretty much everywhere the researchers looked.”

“What’s really heartening about this study and the research is you see people taking the technology seriously, looking at the things it makes possible, the things that it interferes with, the new forms of social exchange that become feasible when you have smart phones and internet and social networks, actually looking at how it affects us as people. It’s really vital that this work continues… It’s a sense of a discipline emerging, or rather that the discipline of anthropology is properly embracing social media as an important part of human society… What they’re doing is identifying core principles, like the fact that social media can help create privacy. It’s a really important insight and that’s not going to change, even if it’s no longer Facebook, it’s something new.” – Bill Thompson, BBC Technology writer

CBBC Newsround (29/03/2016 TV): Two mentions of ‘footies’ on the morning and afternoon programmes.

BBC World Service – (29/02/2016 radio): World Update (from 8:51)

BBC Radio 4 (29/02/2016 radio): Today Programme (from 2:54:32)

Spanish:

BBC Mundo (05/03/2016 online): De “Footies” en Chile a “uglies” en Inglaterra, cómo el mundo cambió las redes

BBC Mundo (09/03/2016 online): La artista argentina de Instagram que engañó a miles de personas

Portuguese:

O Globo (07/03/2016 online and print): Pesquisa mostra diversidade do uso das redes sociais pelo mundo

And here are selected comments from learners on our course:

“Thank you for this course. Although I am a journalist and social media user I now have an understanding of the cross-cultural realities of social media… how it is used differently across different cultures.”

“Fantastic course. This has been a great introduction and it seems like it’s almost limitless as to where one could further go from here in these studies.”

“Really enjoyed the course. I found it extremely interesting with edifying discussions! I hope social media evolves into something truly radical rather than merely, ‘a look at me peep show for the digitally besotted’ (John Pilger)”.

The course has just entered its third week, and it’s not too late to sign up! Join the course in English on FutureLearn and in Portuguese, Tamil, Hindi, Spanish, Chinese, Turkish, and Italian on UCLeXtend.

The launch of Why We Post

By Tom McDonald, on 29 February 2016

Released today: ‘How the World Changed Social Media’

After years of work and planning, we have today launched Why We Post, which represents the results of our project.

This includes three books, as part of a series published by UCL Press, all of which are Open Access and completely free to download.

How The World Changed Social Media is a summary of the findings of our ethnographic research undertaken in eight countries around the world. This is complemented by two full-length monographs Social Media in an English Village and Social Media in Southeast Turkey. Monographs from our other field sites will be published in the coming months.

In addition to this, the results of our project are being unveiled on a new ‘Why We Post’ website, with over 100 videos on our dedicated YouTube channel, as well as via a free e-learning course in English on FutureLearn, at and in seven other languages at UCL Extend.

We’re delighted to get to this stage, and are excited to finally be able to open up the discussion of our research findings with the greater public.

Close

Close