UCL Festival of the Arts: Queer Edwardians: E.M. Forster and D.H. Lawrence

By utnvlru, on 28 May 2015

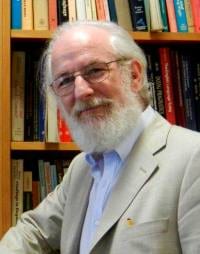

As part of the UCL Festival of the Arts, which ran over five days last week, Dr Hugh Stevens from UCL English Language & Literature presented the lecture Queer Edwardians: E.M. Forster and D.H. Lawrence, on Tuesday 19th May. In this, he explored the representations of same-sex desire in the writings of these two authors in their work before World War One.

Dr Stevens examined a range of short stories and novels by both authors, in particular Forster’s novel ‘Maurice’ and Lawrence’s ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’. He placed these works within context of the authors’ own sexualities and romantic lives, and within that of wider society during the time they were both alive.

Forster’s novel ‘A Room with a View’, and the 1980s Merchant Ivory film of it starring Maggie Smith, Helena Bonham-Carter and Daniel Day-Lewis among other quintessential English actors, will forever remind me of studying for English Literature ‘A’ Level. With its tale of an upper class girl being encouraged to marry a repressed man she doesn’t love, the novel typifies Forster’s earlier writing and the age in which it was written, explained Dr Stevens.

‘Maurice’ on the other hand, a novel that I myself later read (and only recently finally caught the film of starring a very young Hugh Grant), was apparently written after Forster had his first sexual experience with a man and was directly inspired by this; and as a result is much less typical of the time.

As homosexuality was of course illegal until 1967, Forster did not allow ‘Maurice’ to be published until after he died in 1970. He did however write a footnote to the novel in 1960, following the publication of the Wolfenden Report in 1957 which recommended that ‘homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be a criminal offence’. He wrote that a ‘happy ending was imperative’ for the novel, and that he was ‘determined, that in fiction anyway’ a love story between two men should end well.

Close

Close