Unmasking London’s ancient diseases

By Claire J Roberts, on 3 July 2013

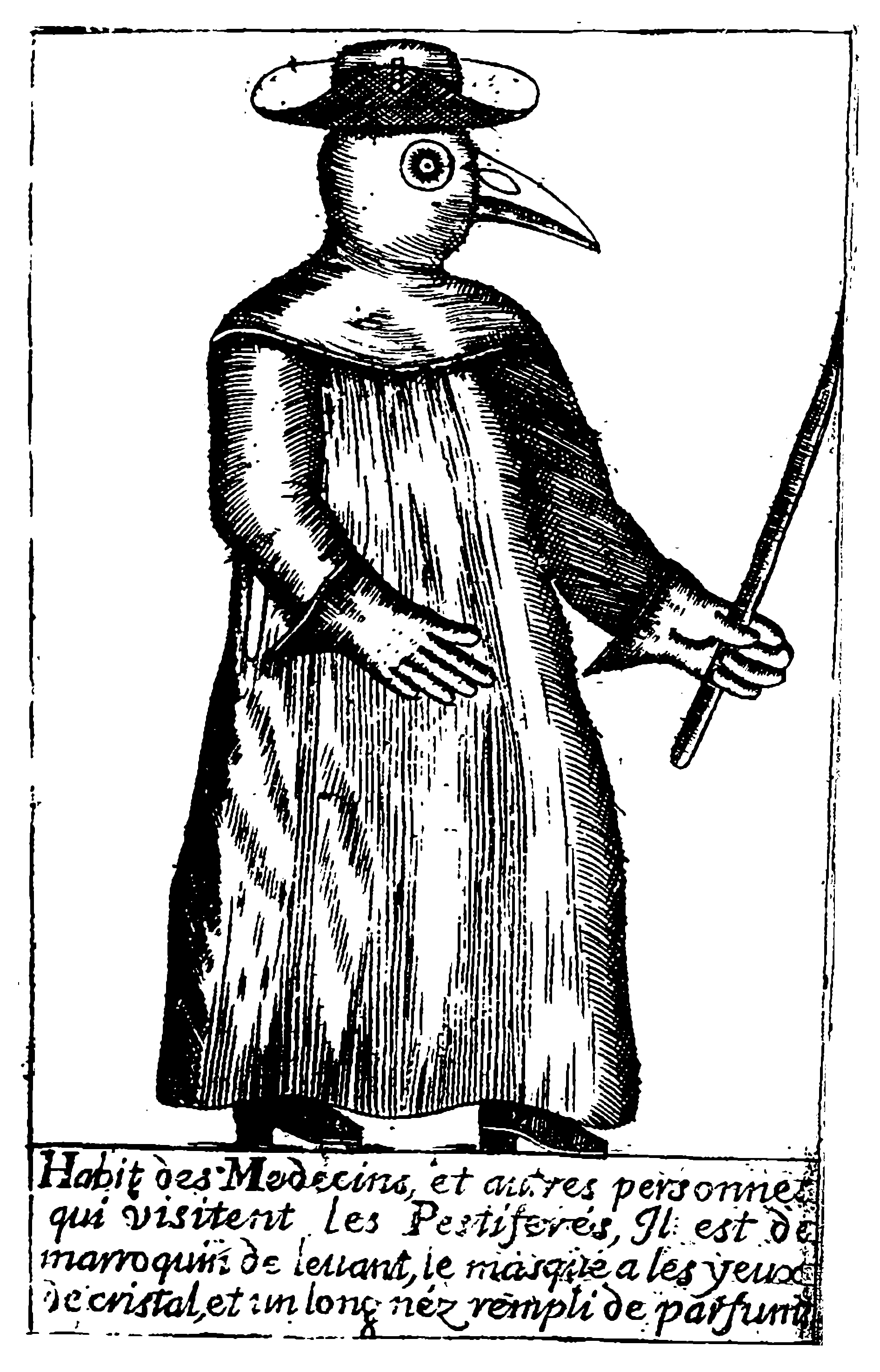

Sat in the auditorium of the Museum of London on 18th June, waiting for Dr Carol Reeves (UCL History of Medicine) to begin her Lunch Hour Lecture on the Black Death, it was a chilling introduction to the subject to see fully-robed plague doctors make their way slowly through the crowd chanting “make way, make way for the plague doctor”.

Although the illusion was slightly broken when one dropped their bell and another’s awkwardly-fitting hat and mask meant a brief encounter with the wall, I began to get a sense of the seriousness and superstition with which doctors, clergy and sufferers alike treated the plague during its first European pandemic from 1348.

An ‘arrow of God’

A de-masked Dr Reeves first explained how the Black Death, which killed up to half of the population of medieval Europe in just five years, was understood by those who experienced it.

One of the ‘three arrows of God’ (along with war and famine), the disease was seen as a punishment from above and even linked to astrology, given its proximity to a massive Italian earthquake around the same time of the outbreak.

The Black Death, then known simply as the plague or pestilence, could kill victims within three days of infection, giving the small number of elite physicians and more common plague doctors a narrow window of time to administer an incredible array of remedies.

Plague doctors filled the beaks of their masks with herbs to ward off bad air and carried fumigating torches.

Treatment for infected patients varied wildly and included bloodletting and purging; using a lancet to pierce buboes (which was thought to help, but would actually have spread the disease further); putting frogs, snakes and crabs on a lancet and rubbing the buboes; and cutting up a live puppy then pressing it to the chest of the patient.

Perhaps the most bizarre – for which Dr Reeves offered a child’s talented visual interpretation from a competition she had run – was to sprinkle salt on the bottom of a chicken and rub it on the armpit…

Crossrail’s discovery

Moving swiftly on to London’s experience of the Black Death, Dr Reeves presented a shocking statistic: the city’s population shrank from between 60–80,000 to 40,000, within one generation. The sheer scale of death meant that emergency cemeteries had to be opened, including one in West Smithfield, near Charterhouse Square.

During excavation for the Crossrail project in early 2013, this cemetery was discovered and work carried out to uncover and preserve 12 skeletons, of what may have originally been more than 15,000, giving scientists the opportunity to discover more about the nature of the disease.

Tooth pulp from the 600-year old skeletons was filtered and scrutinised using cutting-edge technology – eventually leading to the identification of ancient yercinia pestis, a bacterium carried by fleas and spread by rats, which is now recognised as the cause of the Black Death.

Dr Reeves explained that modern strains of yercinia pestis have evolved from this ancient strain, with the plague’s last great pandemic recorded between 1855–1914, killing 10 million people in India, Hong Kong and China. Even in 1900, Londoners were still wary of its return to the west, dunking rats in oil to kill potentially infected fleas.

Bad airs and agues

Another disease to make a mark on London’s history was Marsh Fever, which especially affected those who lived along the marshy banks of the Thames with a fever, or ‘ague’.

In 1724, Daniel Defoe wrote of scenarios where ‘fen men’ who lived in these areas and had developed some immunity to the disease, sought upland wives who would die quickly after the move – some had as many as 15 wives in their lifetime.

These agues, carried by so-called ‘bad airs’ (or ‘mal arias’), also have links to contemporary society. Dr Reeves’ own research aims to show that the malaria we know today in sub-Saharan Africa is comparable to the Marsh Fever common in London more than three hundred years ago.

At the end of the incredibly enlightening lecture, which both contextualised historical diseases and tied them to very modern issues, a question was raised as to how exactly to treat London land rumoured to be an ancient plague burial site.

Sharon Whittle, a colleague of Dr Reeves who worked on the West Smithfield cemetery, answered enthusiastically from the audience: “If anyone knows of a plague pit, excavate it and get someone to call me!” Perhaps, given all the above, it’s better left to the professionals.

View a video of the lecture here:

Close

Close