Lunch Hour Lecture: Still Lives — Death, Desire and the portrait of the Old Master

By Ella Richards, on 4 March 2016

Dr Maria Loh (UCL History of Art) opened her Lunch Hour Lecture on Renaissance self-portraits with a very contemporary comment on self-presentation.

“Hair matters”

Speaking as Hillary Clinton campaigns to be the next President of the United States, Dr Loh quoted Clinton’s Yale University commencement speech from 2001: ”hair matters…Your hair will send significant messages to those around you. What hopes and dreams you have for the world… Pay attention to your hair, because everyone else will.”

Dr Loh argued that Clinton’s words resonated more widely than we might realise. Showing the theatre the evolution of David Beckham’s hair and reminding us of the message that Britney Spears sent out when she shaved all of her hair off, Loh noted that the hairstyle of a Roman bust is often a key indicator of the period of the sculpture.

Renaissance self-portraits

Sofonisba Anguissola, 1556

via Wikimedia Commons

With this in mind, Loh presented her first old master: Sofonisba Anguissola.

Sofonisba Anguissola was one of the great portrait artists of the Renaissance period and Dr Loh argued that in an early self-portrait Anguissola sought to make her ambitions clear.

She stands with neatly parted hair holding a shield that declares “The maiden Sofonisba Anguissola, depicted in her own hand, from a mirror, at Cremona”, an explicit act of self-presentation that directs the onlooker’s interpretation of her image.

Anguissola’s desire to control her own image was a lifelong trait. When Anthony Van Dyck painted Anguissola in her 90s, she told him to not position the light in the portrait too high lest the “shadows in the wrinkles of old age should become too strong.”

Images of the artist: the difficulty of control

Sofonisba Anguissola by Anthony Van Dyck,

1624 via Wikimedia Commons

Anguissola got her way, and in Van Dyck’s portrait she looks good for a woman entering her tenth decade. Michelangelo, however, was not so lucky. Painted by Giuliano Bugiardini wearing his sculptor’s head cloth, Michelangelo purportedly thought that the artist had positioned his eyes incorrectly.

It was here that Loh got to the nub of her point: with the onset of mechanical printing and the growing fame of artists, the Renaissance period was the first time in which one lost control over one’s image once it was created. In fact, the painting that displeased Michelangelo was widely copied and distributed.

Moreover, Dr Loh pointed out that even if one is happy with an image of oneself, one cannot control how that image is reproduced.

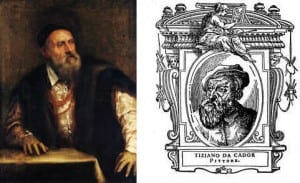

Titian’s self-portrait and Vasari’s interpretation

via Wikimedia Commons

Titian’s widely acclaimed self-portrait was the template for Giogio Vasari’s woodcut of Titian for his 1568 book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, a book that demonstrates the emerging celebrity culture surrounding famous artists of the period.

Dr Loh suggested that Vasari had an axe to grind: his interpretation of Titian’s self-portrait shows the famous painter with deep wrinkles, a spindly nose and ragged beard.

Artistic frustration

Annibale Carracci,

Self-Portrait on an Easel in a Workshop,

1604 via Wikimedia Commons

Although we do not know what Titian thought, we know that many other artists disagreed with Vasari’s book: El Greco painted over the portrait of Titian in his personal copy, and Annibale Carracci annotated his copy, calling Vasari “ignorant”, “malicious” and adding a number of nouns inappropriate for this blog.

Dr Loh suggested that perhaps Carracci’s frustration was due to his own awareness that one’s legacy rests on the images of oneself that are left behind.

In her final portrait, Dr Loh turned to Carracci’s later, melancholic self-portrait, painted when the artist had lost both his patron and a number of members of his family.

Dr Loh described the image as a “still life”, as Carracci plays with the lines between art and reality, including a painting pallet into the portrait, and painting himself with such detail that there is perhaps a part of the artist still alive in the portrait.

Fickle portraits

Dr Loh’s message was clear: how you are presented matters, especially if you are famous; in her own words, “Images can preserve you, but they can also betray you.”

Renaissance artists realised this and often sort to exert control by painting themselves. The painters’ growing celebrity, however, meant that these self-portraits were often copied, distorted and distributed outside of their control.

It is a frustration with which I am sure David Beckham, Britney Spears, and Hillary Clinton would empathise.

Close

Close